A volcano scorched hundreds of Roman scrolls — can AI recover their text?

Despite early breakthroughs, it could take years to decode all the surviving scrolls.

In the summer of 2023, Luke Farritor was a 21-year-old college student doing an internship at SpaceX. He spent his evenings on a project that turned out to be far more significant: training a machine learning model to decode a charred scroll that was almost 2,000 years old.

The scroll was one of about 800 that had been buried in AD 79 by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The scrolls were rediscovered in the 1700s in the nearby town of Herculaneum, but the first few scrolls crumbled when archeologists tried to unroll them. Conventional imaging techniques have proven ineffective because carbon-based ink is indistinguishable from the charred papyrus.

The Vesuvius Challenge was launched in March 2023 by tech entrepreneurs Nat Friedman and Daniel Gross and computer scientist Brent Seales. Seales had been working on techniques to “virtually unwrap” intact scrolls using data from non-invasive scans.

Friedman and Gross helped to raise $1 million in prize money to encourage people to help improve those techniques. The prize money attracted more than a thousand teams — Farritor had joined one of them.

Another contestant, Casey Handmer, had noticed a faint but distinctive “crackle pattern” left by ink residue on the surface of the papyrus. Farritor took that insight and ran with it.

Farritor “saw Casey’s crackle pattern being discussed in the Discord, and began spending his evenings and late nights training a machine learning model on the crackle pattern,” according to the official announcement of Farritor’s breakthrough. “With each new crackle found, the model improved, revealing more crackle in the scroll — a cycle of discovery and refinement.”

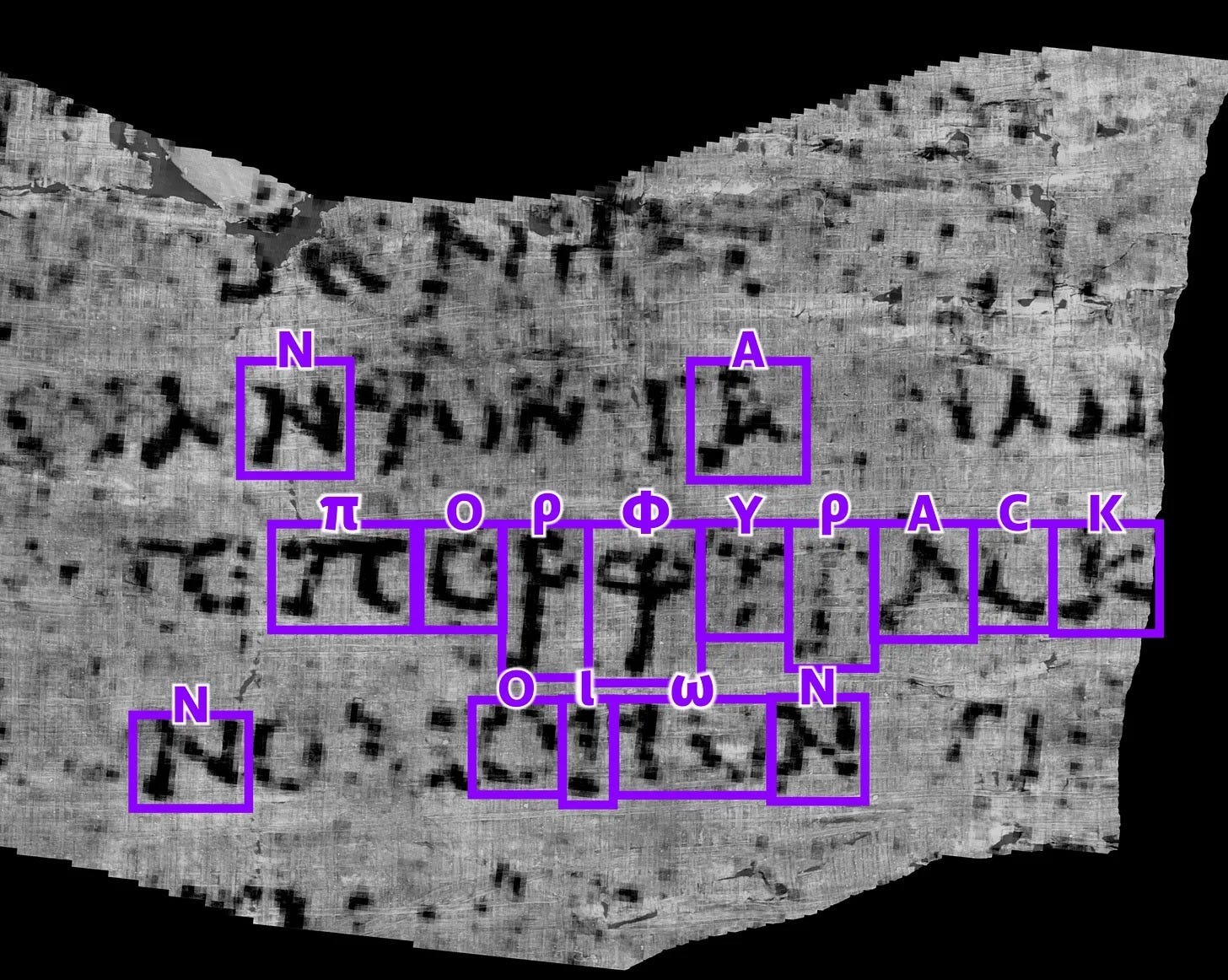

One August night, his software started to reveal traces of ink that were invisible to the human eye. Enhanced, they resolved into a word: ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ. Purple.

It was the first time text had been recovered non-invasively from a Herculaneum scroll; Farritor went on to win a share of the $700,000 Grand Prize alongside two other researchers in 2024.

These scrolls are believed to contain Greek prose that largely vanished elsewhere, including philosophical works from the Epicurean tradition that were rarely recopied because they conflicted with Christian doctrine.

“We only have very few remaining authors of Greek prose who have been preserved in the Middle Ages,” said Jürgen Hammerstaedt, a classicist at the University of Cologne who has studied the scrolls for decades.

Maria Konstantinidou, an assistant professor at Democritus University of Thrace, shares the excitement. “There are so many works out there that nobody has the time and processing power to understand or to know,” Konstantinidou told me.

But to produce text that’s useful to papyrologists, someone needs to turn those early breakthroughs into a cost-effective pipeline for decoding scrolls at scale. There are around 300 intact scrolls waiting to be decoded, but experts told me this could take several years using today’s techniques.

What it takes to decode a scroll

In February 2024, Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor, and Julian Schilliger won the challenge’s $700,000 Grand Prize for recovering 15 columns from a sealed scroll — over 2,000 characters in total.

Their pipeline was an impressive technical achievement, bringing together virtual unwrapping, ink detection, and expert interpretation to recover readable text from a sealed scroll. But it was far from fully automated.

The process begins at a facility like the Diamond Light Source particle accelerator near Oxford. When the Vesuvius Challenge was announced, researchers had already performed high-resolution scans using X-ray computed tomography (CT). This produced several terabytes of three-dimensional data per scroll.

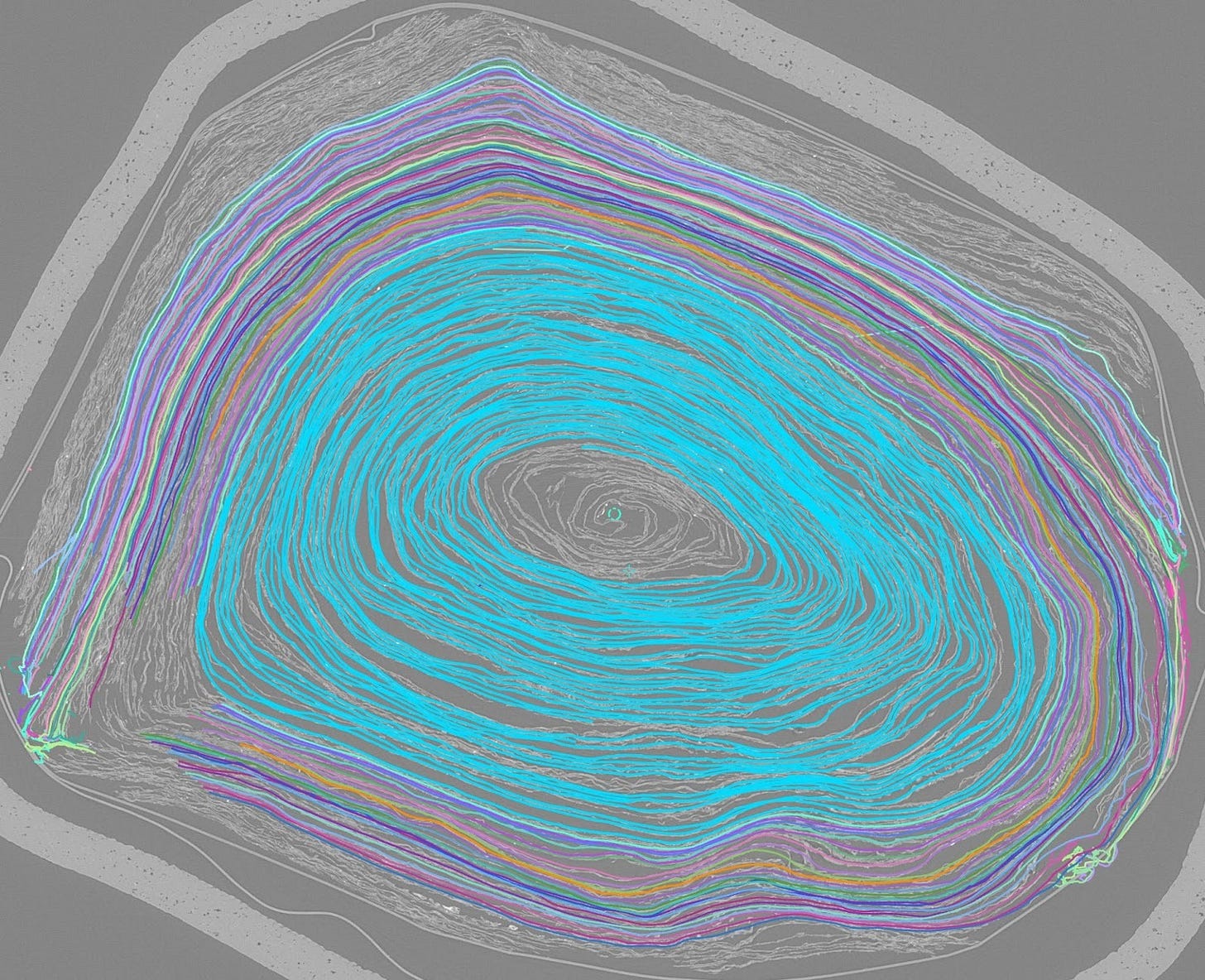

The next step is segmentation — identifying and separating the individual layers of papyrus inside the three-dimensional CT scan. Some scrolls would be more than a dozen meters long if they were unrolled. After 2,000 years of compression, surfaces have warped, torn, and been pressed together.

Julian Schilliger, who won the Grand Prize alongside Farritor, created the segmentation software used to virtually unroll scanned scrolls. The system combines machine learning models with traditional geometry-processing techniques. It can handle “very mushy and twisted scroll regions,” and it enabled ink detection in areas that had never been read before, including parts of a scroll’s outermost wrap. But it still requires extensive human oversight to correct errors such as self-intersections, surface breaks, and misidentified layers.

Two years later, workflows are still only partially automated. Machine learning helps propose likely surfaces and geometries, but humans still intervene to refine those surfaces and make them usable for reading. That isn’t cheap. Even with help from the latest algorithms, it costs about $100 per square centimeter in labor and processing time. At that rate, virtually unrolling all 300 scrolls would cost hundreds of millions — if not billions — of dollars.

Fully automating the unrolling process remains difficult in part because of limited training data, according to Hendrik Schilling, a computer vision expert who participated in the Challenge. For most scrolls, “we only have the CT scans that don’t have a reference of what it looks like unrolled,” leaving algorithms with little ground truth to learn from. Creating more training data requires a lot of expensive human labor.

Segmentation produces a three-dimensional mesh that traces the twists and turns of each papyrus sheet. This mesh must then be flattened into the two-dimensional format required by computer vision models. It’s important to minimize distortions during this process, because even small errors can destroy faint ink signals. The system captures 32 layers above and below the segment surface (65 total) to help capture locations where traces of ink may be present.

The next step is to detect ink on the surface of the (virtually) unrolled papyrus. The winning team used deep learning to do this. Specifically, they adapted a Facebook-created model that was originally designed to understand video. They treated the unrolled papyrus as a video sequence where spatial slices at different depths become analogous to video frames. To improve redundancy, they combined this model with two others; multiple architectures producing similar results served as mutual validation.

Traces of ink were first detected in tiny patches before being aggregated into larger shapes. To minimize the risk of hallucinations, the model did not rely on any pre-existing knowledge about the shape of Greek letters.

Training data for the ink detection model came from two sources. First, fragments from historical unrolling attempts provided ground truth through infrared photography revealing surface ink. The second source was those “crackle” patterns discovered by Casey Handmer and Luke Farritor. The breakthrough came when Youssef Nader figured out how to train a single model using both data sources. He first pretrained the model using unlabeled crackle data, then fine-tuned it with human-labeled infrared images.

At the pipeline’s end, scholarship took over. Ink detection models output noisy probability maps showing the likelihood of ink at each pixel. These went to a papyrology team that assessed stroke shapes, letter forms, spacing, and philological context. Ultimately, human experts decide what constitutes text, how it should be read, and what it means.

The architecture of the Challenge

The Vesuvius Challenge has an unusual structure blending competition with cooperation, crowdsourcing with institutional support, and prize incentives with open-source requirements. Its March 2023 announcement attracted interested contestants from around the world. Some had deep expertise in relevant fields. Others were complete amateurs.

Sean Johnson was working for Wisconsin’s Department of Corrections when he saw an article about the Vesuvius Challenge on Bing’s landing page. He had no degree or programming background, but he wanted to help out.

“I’m not great with coding or any of the super technical aspects of this project, but I have a Vyvanse script and a lot of free time,” Johnson wrote on the Vesuvius Challenge Discord in October 2023. “Is there any task here that is constrained by just time-consuming manual work?”

“I’d never written a Python program or done any machine learning,” Johnson told me. He taught himself through online courses and “mostly just battling with ChatGPT.” Progress was uneven. “I’ve just kind of thrown my head at it over and over and over again,” he said.

But when a pipeline worked end to end, the payoff felt disproportionate. It’s an “Indiana Jones kind of thing,” he said. “Boom. You’re looking at a word. You’ve ripped a word from the ether, out of history.”

Schilling, the computer vision expert, joined because he enjoys a technical challenge. “I want to work for something that does something meaningful, but I’m not some archeology nerd,” he told me.

Johnson told me that the Vesuvius Challenge had a different structure than other competitive machine-learning platforms like Kaggle, which tend to reward people for short, well-defined tasks. Decoding the Herculaneum scrolls “can’t really be packaged into a discrete little package,” Johnson said. The full pipeline involves “100 steps, and each one of them is its own subfield.”

If the competition had been limited to a single Grand Prize, that would have incentivized hoarding breakthroughs and reduced the probability any team could assemble all necessary pieces. So the organizers also offered “progress prizes” — typically $1,000 to $10,000 — every few months. To win a prize, contributors had to publish their code or research as open source, leveling up the entire community. Progress prizes allowed winners to reinvest in equipment or time. The process also helped people find collaborators, as happened with the Grand Prize winners.

In early summer 2023, organizers hired an in-house segmentation team to address a core bottleneck: before any ink could be detected, someone had to identify and trace the papyrus layers. It was hard for non-experts to judge whether they had unrolled a scroll correctly without working ink detection, creating a chicken-and-egg problem. Over several months of painstaking manual work, the team produced roughly 4,000 square centimeters of high-quality flattened surface segments, giving contestants shared reference material that significantly accelerated progress.

The decision proved crucial. It led to Casey Handmer’s discovery of the “crackle pattern,” the first directly visible evidence of ink within complete scrolls. The in-house segmentation team worked closely with community contestants to produce better segmentation software. Schilling told me that the organization “works a bit like a startup. Many people do many different jobs and switch around and so on. It’s quite flexible.”

The Challenge also relies on institutional partners. Papyrology work involves scholars from the University of Naples Federico II, the University of Pisa, and other institutions. Scanning is coordinated with the Institut de France, which holds some scrolls. The broader network includes the Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, which houses hundreds of scrolls, requiring ongoing coordination with Italian authorities.

Technical barriers to automation

The pipeline developed by the Grand Prize-winning team proved effective for one scroll, but its applicability to others remained uncertain. So the organizers of the Vesuvius Challenge set out to rebuild it into something that could work scroll after scroll. But rather than announcing another Grand Prize immediately, they introduced category-based awards for tasks such as segmentation, surface extraction, and title identification.

In May 2025, one of those intermediate awards, the $60,000 First Title Prize, was claimed when researchers recovered what appears to be the title of a still-sealed Herculaneum scroll: On Vices by the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus.

Johnson, who worked on the segmentation for that scroll, recalled that the first renderings were barely legible. After additional refinement, he showed one image to papyrologist Federica Nicolardi, who read it immediately. “Blew my mind,” he said. Two other teams later produced clearer results and formally won the prize.

But there was an important caveat. “That part of the scroll was mostly manually unrolled,” Johnson told me. The methods used for the 2025 First Title Prize were not fundamentally different from those used in 2023; they were extensions of the same semi-automatic techniques, applied carefully to especially promising regions of a scroll.

So the central question has shifted from whether text could be recovered at all to whether it could be done routinely. At the current pace, processing the full Herculaneum library would take several years. The Vesuvius Challenge Master Plan, published in July 2025, outlines a series of steps intended to compress that timeline. These include improved surface extraction, deeper automation, and tools designed to reduce manual intervention at every stage.

According to Schilling, the problem is not that current methods fail outright, but that they require too much human steering.

“It’s not as fast or effective or cheap as it should be,” he told me. “Right now, we have solutions that work but that require human input.” What researchers want instead is a “global optimal solution” — a system that can isolate papyrus surfaces, unwrap them, and detect ink reliably across many scrolls without constant correction.

Scanning itself is a constraint. High-resolution scans are expensive, scarce, and slow to schedule, and variations in scan quality introduce noise at every downstream stage. So researchers have worked to improve scanning protocols, reduce artifacts, and develop methods that can tolerate uneven or lower-quality data across the collection.

To support that shift, the Challenge has expanded beyond its original crowdsourced model. Coordination with museums, governments, and scanning facilities has become central, alongside full-time staff, institutional partnerships, and longer-term funding. There is no fixed endpoint — only a growing archive of unread material, and a pipeline that is still learning how to scale.

Progress, patience, and predictions

Predictions about when scrolls will be fully readable vary widely.

“We feel like we’re going to get this solved within the next year,” Johnson told me. But then he immediately qualified his own statement: “I’m a hopeless optimist. If you asked me at any point over the last two years, I would have told you we could solve it next week.”

The project has been an emotional roller coaster for Johnson. “You go through parts of it where you’re just in despair,” he said. “You’re like, what the hell am I even doing? And then the next day you have this huge breakthrough.”

Schilling is measured but hopeful. “It’s always gradual progress over time,” he said. “The principal problem is solved. Now it’s about generalizing and speeding it up. This could still mean there’s quite a lot of stuff to be done, but at the same time, we can already unroll scrolls, so the process is working.”

“I think that in the next year we can probably automate quite a bit,” he added. “I wouldn’t be surprised if by the end of [2026] we have a really automated method.”

But Jürgen Hammerstaedt, drawing on his decades of papyrological experience, counseled patience.

“I understand that there’s still a long way to go in many regards, but that’s normal in papyrology,” he said.

Not a fan of having AI “recreate history” artificially … a slippery slope

Amazing anyway.

And what about that? 👇

AI is transforming the translation of ancient Babylonian tablets by enabling faster, more accurate interpretations of cuneiform texts. Machine learning models, such as those developed by researchers at Tel Aviv University and Cornell, can now translate Akkadian with high accuracy, particularly for administrative and royal texts.