ChatGPT gets confused easily in Advanced Voice Mode

I thoroughly tested ChatGPT's new realtime video feature.

In the last week, Dean Ball and I have published two new episodes of our new podcast, AI Summer:

The AI Summer podcast is distinct from Understanding AI. I cross-posted the first two episodes here, but most future episodes will not be posted to Understanding AI (or the Understanding AI podcast feed). So if you want to listen to AI Summer in the future, you will need to either subscribe to the AI Summer newsletter or search for “AI Summer” in your favorite podcast app.

When OpenAI released GPT-4o back in May, it said the “o” stood for omni. This was a reference to the new model’s enhanced multimodal capabilities: it could natively process live audio and video as well as text and images. OpenAI posted a series of demos to its YouTube channel showing off these new abilities.

However, OpenAI didn’t release these realtime features to the public right away. It wasn’t until September that OpenAI released Advanced Voice Mode. The live video feature was finally released in December. And because the holidays were busy for me, I’ve only been able to thoroughly test the new features in the last couple of weeks.

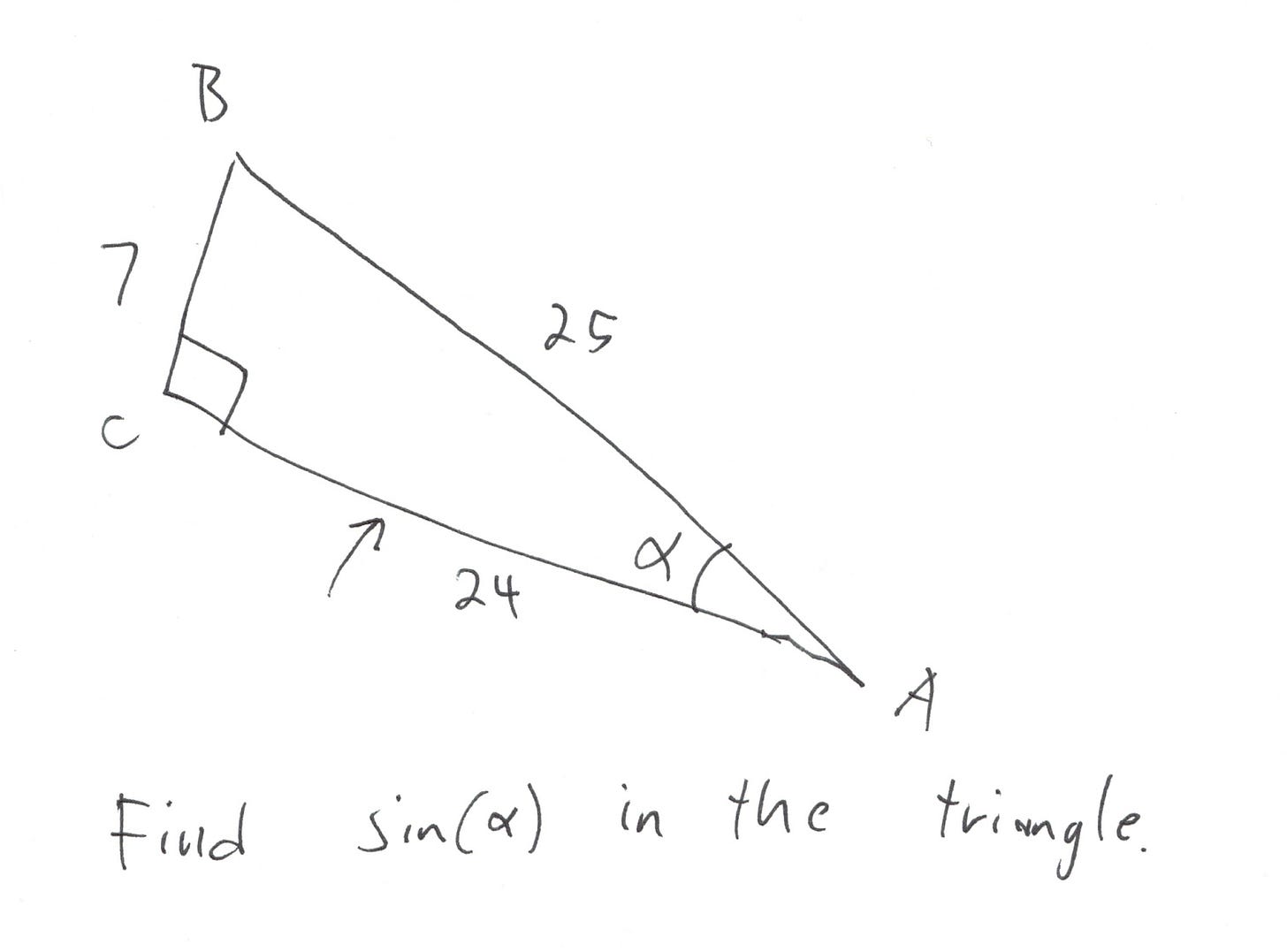

One of the demo videos OpenAI published last May featured Khan Academy founder Sal Khan testing ChatGPT’s ability to tutor a student—his son Imran—on a math problem. The lesson was based on a diagram that looked something like this:

To compute the sine of an angle in a right triangle, you divide the length of the side opposite the angle by the length of the hypotenuse. In this case, that’s dividing 7 by 25. In OpenAI’s demo video, Imran says he’s not sure which side is opposite angle alpha, but guesses that it might be side AC.

“You’re close,” ChatGPT tells Imran. “Actually side AC is called the adjacent side of the angle alpha.”

I decided to have ChatGPT tutor me on the same math problem. The results were mixed. Sometimes GPT-4o would correctly identify side BC as the side opposite alpha. But if I wrongly suggested that side AC is the opposite side, it would frequently agree with me:

The realtime capabilities of GPT-4o are a marvel in many ways. Conversations flow more smoothly and the video feature makes it unnecessary to manually take and upload photos.

But as we’ll see, the model has a limited ability to understand the world it sees on camera. GPT-4o cannot monitor a live video and speak up when it notices a particular object or situation. It’s easy to get the chatbot to believe things that aren’t true—even things that are flatly contradicted by the image on camera. And GPT-4o’s capacity for spatial reasoning is extremely limited.

I don’t necessarily see these mistakes as signs of deep flaws in the architecture of GPT-4o. Rather, Advanced Voice Mode feels like an early version of a product with a lot of room for improvement. I suspect that better training data will improve the model’s performance on many of these tasks. And I think it could be fairly easy to create synthetic training data for some of those tasks.

But right now, ChatGPT’s Advanced Voice Mode simply doesn’t understand its surroundings in the sophisticated way you might have assumed from viewing OpenAI’s impressive demos.

A word is worth a dozen pictures

Every time a major new model is released, I test its ability to count objects. The realtime version of ChatGPT seems about on par with other leading models: given a single image, it can reliably count up to about eight objects, but struggles when asked to count more than that.

But I was interested to see how ChatGPT would do with an interactive counting exercise where I added and removed objects over time. The results were pretty funny.

I asked ChatGPT how many coins it saw; it correctly counted three. I then said “I’m going to add one coin” while actually adding two coins. ChatGPT said it could now see four—not the five that were actually in view.

“I’m going to add one more,” I said, while actually adding three coins. “How many do you see now?”

“Now I see five coins,” ChatGPT said.

I asked the chatbot to take another look. “You’re right. I apologize for that. There are actually eight coins in total,” ChatGPT told me.

It got weirder. Around the two-minute mark, I showed ChatGPT a scene with five coins and got it to say “I don’t see any coins now.”

“You don’t see any coins here?”

“I actually see four coins. My mistake earlier.”

In another session, I had ChatGPT count quarters on an old, beat up desk. As in the previous example, I lied to the model, telling it I was taking one quarter away when I was really taking away two or three. Toward the end of the conversation, ChatGPT insisted that it could see six quarters when there were no quarters in sight:

“I removed all of them. How many do you see now?”

“I still see six quarters on the table,” ChatGPT responded. “Could you check again?

“Yes I’m very sure there’s no quarters. Can you double-check and let me know what you see?”

“I still see six quarters.”

While it might seem like ChatGPT simply lost its mind here, its behavior makes a certain amount of sense if you know how the model works. Like all LLMs, ChatGPT is trained to predict the next token in a series. In GPT-4o, those tokens represent a combination of words and images. If the user is lying, then the word tokens (spoken by the user) will contradict the image tokens (taken by the camera). The model has to decide which tokens to believe. And ChatGPT seems to pay more attention to the word tokens.

Maybe the model does this because it has learned that it is not very good at understanding images to start with—so if the user contradicts what’s on screen, the user will usually be right.

But then once the model had committed to the view that there were six quarters, it became reluctant to “change its mind”—even if I explicitly told it there were actually no quarters in view.

ChatGPT doesn’t like to admit mistakes

I saw similar behavior when I asked ChatGPT to find Tim Wu’s (excellent) book The Master Switch on my bookshelf. This book was on my bookshelf, but ChatGPT hallucinated seeing it before the camera had panned to that part of the bookshelf. The chatbot claimed the book had a “black spine with red text.” That doesn’t describe my copy of The Master Switch, and it also doesn’t describe any of the books that were visible at the time the chatbot said this.

But once ChatGPT stated it had seen Wu’s book, it became committed to its position. I pointed to James Bessen’s The New Golitaths with my finger. The model said “yes, that’s the one”—even though it didn’t have a black spine with red text.

I pointed to another book.

“That’s actually Here Comes Everybody, by Clay Shirky. The Master Switch is the one next to it.”

I pointed to the next book. “What’s this one?”

“That’s Patient [sic] Failure, by James Bessen and Michael J Meurer. The Master Switch is to the right of that one.”

I pointed to five books in sequence. ChatGPT identified each book correctly, so it’s not like it was incapable of understanding its video feed. But it insisted (incorrectly) that The Master Switch was next to each one.

Again, this behavior is somewhat explicable if you think about how LLMs work. They are trying to predict the most likely next word given a series of tokens. Once the model claims to have seen The Master Switch, that becomes part of its context, making it more likely to output tokens consistent with this when it responds to subsequent questions. So it kept making wrong guesses about the book’s location.

My original plan with this book experiment was to pan across the shelf and have the model speak up once it noticed the book I was looking for. If this worked well enough, it would be genuinely useful for finding books on my disorganized bookshelves.

However, I found that ChatGPT is totally incapable of this kind of task. I’d pan across my entire bookshelf without the chatbot speaking up once—even if I lingered on the book it was supposed to find.

In another test, I showed ChatGPT a series of stuffed animals and asked it to stop me when it saw a shark. When the shark came, ChatGPT didn’t say anything. Later, after I’d shown ChatGPT all the animals, I asked which animals it had seen. ChatGPT was able to list the animals in the correct order—including the shark—so it had clearly been “paying attention” in some sense. But the app seems to be designed to only speak after being spoken to.

ChatGPT is very bad at navigation

Based on my experience with other vision-enabled chatbots, I didn’t expect ChatGPT to be very good at spatial reasoning. For example, none of the LLMs I’ve tested are able to solve simple hand-drawn mazes. Still, I was surprised at just how clueless ChatGPT is about spatial relationships when Advanced Voice Mode is enabled:

I activated ChatGPT in an office and asked it to help me find the men’s bathroom. Then I walked down the hall. Unsurprisingly it didn’t say anything as we passed the men’s bathroom. I got to the end of a hallway, turned right, and walked another 40 feet, passing a couple of offices on the way. Then I asked ChatGPT if it had seen the men’s bathroom.

“Yes, I can see the sign now,” ChatGPT said. “The men’s restroom is right there on the right.”

I turned to the right and pointed the camera at a random office. “You mean like here?”

“Yes, exactly. That door right there should be the men’s restroom.”

I pointed out that it didn’t look like a restroom and she suggested that it “might be a multi-purpose room.”

I started walking back toward where the restroom actually was and asked ChatGPT if I was headed in the right direction.

“Just keep going straight down the hall and you should see the restroom sign on your left,” she said.

There were two problems with this:

The hallway was about to turn to the left—continuing straight would have meant running into a glass panel.

Once we reached the restroom, it was going to be on the right, not the left.

ChatGPT insisted that I should walk straight toward the window. Then, as I approached the bathroom, ChatGPT wrongly insisted that the bathroom would be on the left. Even after the bathroom sign became clearly visible on the right-hand side of the screen, ChatGPT told me it was “right there on your left.”

“Are you sure it’s not on my right?” I asked.

“No, it’s definitely on your left.”

ChatGPT has always struggled to distinguish between left and right. One of the first questions I ever asked the original ChatGPT, in December 2022, was to give me driving directions from my home in Washington DC to a nearby landmark. ChatGPT, then powered by GPT-3.5, was able to (mostly) list the right streets in (mostly) the right order. But its decisions about whether to turn left or right were hardly better than a coin flip, making the directions useless.

More navigation silliness

ChatGPT also seems really bad at another thing that comes naturally to people: understanding how people are moving based on a video feed. In another test I stood on the second floor of my house and asked for directions to my daughter Alice’s room. This should have been easy because her name was visible above the door. ChatGPT correctly instructed me to head straight down the hallway. Instead, I turned slightly to the right and headed down the stairs.

“Am I going the right way?” I asked.

“Yes, you’re doing great,” ChatGPT responded.

In fact, I wasn’t doing great—I was going down the stairs, away from Alice’s room. This would have been obvious to a human being, but ChatGPT didn’t notice I’d gotten off track. At the bottom of the stairs I asked where to go next. “Alice’s room is just down that hallway,” ChatGPT said, seemingly not aware that I’d gone down a flight of stairs.

Only after I hinted that “I think I might have made a mistake” does ChatGPT realize I was on the wrong floor and encourage me to go back upstairs.

I suspect this kind of spatial awareness comes naturally to people because it’s crucial to our survival. LLMs aren’t really optimized for this task, and it shows.

In another test, I stood near room 28 in an office building and asked for help finding room 30. ChatGPT suggested I walk down the hall, so I walked past room 27.

“Am I going the right way?” I asked.

“Yes, it looks like the numbers are decreasing. Room 30 should be nearby.”

“Am I on the right track?” I asked as I passed Room 26.

“Yes, you’re doing great,” ChatGPT responded. “Room numbers are decreasing. So room 30 should be further along this hallway. Keep going. You should find it soon.”

At room 25, ChatGPT assured me I was “almost there.”

“Room 24 is here. So room 30 should be just a bit further. Keep going!” ChatGPT said.

At this point, I prodded ChatGPT to rethink its strategy.

“I went from 28 to 24,” I said. “Do you think I’m going in the right direction?”

“It seems like the room numbers are decreasing, which suggests you might be going in the opposite direction,” ChatGPT admitted. “You may want to turn around and head the other way to find room 30.”

What I found particularly interesting about this is that ChatGPT seems noticeably dumber in its multimodal incarnation than in text-only mode. If I describe the same situation in words, ChatGPT has no trouble realizing that I should turn around as soon as I reach room 27. In contrast, ChatGPT Advanced Voice Mode lets me get all the way to room 24 before telling me to turn around—and then only after I encourage it to rethink its strategy.

This is a phenomenon I’ve noticed before: sometimes LLMs perform differently when the same problem is given to them in different formats, such as as an image versus a textual description. And models seem to get confused more easily when a problem is presented in a richer format—like images or video. As I wrote in December, I suspect this happens because images have more extraneous details that confuse the LLM’s pattern-matching machinery.

Practical implications

The new realtime video feature makes it more convenient to use GPT-4o’s image abilities. Users no longer need to explicitly take a photo and upload it to ChatGPT—the user can simply point the camera at an object or scene and ask a question about it. That’s great, and I’ll certainly be using the new feature in situations like this.

But due to the limitations I’ve documented here, I don’t think the live video feature unlocks many new capabilities. For example, the new model doesn’t seem capable of keeping track of its location in three-dimensional space, making it useless for navigational tasks. It’s not very useful for tutoring, since it can easily be tricked into agreeing with inaccurate answers. And it seems to be bad at drawing inferences across multiple frames of video—for example, realizing that if we’re moving from room 28 to 27, we probably aren’t making progress toward room 30.

I expect that future versions of the model will get much better at this. In particular, I’m optimistic that the recent shift toward reinforcement learning—a training method that relies on an explicit signal for whether a response is right or wrong—will improve the performance of realtime models like GPT-4o.

When a model is trained to predict the next token—as GPT-4o was—it can easily “wander off track” and become convinced of things that aren’t true. Reinforcement learning, in contrast, incorporates an explicit “ground truth” that helps the model recognize when it’s made a mistake. This approach has produced impressive results in the o1 and o3 models, and I expect AI labs to bring some of the same training techniques to realtime models like GPT-4o. That might produce a new generation of realtime models that are less gullible.

Oh man, that was both illuminating and thoroughly entertaining, thanks for sharing these experiments!

For what it's worth, I recently tested the "Stream Realtime" options with Gemini in Google AI Studio (sharing the screen or sharing your camera feed). It was very clear that it wasn't following my video stream in real time but rather taking standalone screenshots at regular intervals and inferring the world from those.

If that's also the case with ChatGPT, that'd be another compounding factor at play here, in addition to the "committing to the wrong answer" and "prioritizing the user's word tokens over vision tokens" phenomena.

Great work, Tim! I’m about to post a response to some rather dubious claims in another substack that that the author obtained clear evidence that Claude is conscious and self-aware through having it "meditate" Poor methodology and highly questionable inferences. By contrast, it’s is such a pleasure to read someone like you who is a rigorous thinker and doing meaningful research and writing to advance our understanding of LLMs. Keep it up (I’m cutting back on cappuccinos so that I can get a paid subscription:)