Do driverless cars have a first responder problem?

Waymo continues to bolster its safety case—Cruise not so much.

I’m a journalist with a computer science master’s degree. In the past I’ve written for the Washington Post, Ars Technica, and other publications.

Understanding AI explores how AI works and how it’s changing the world. If you like this article, please sign up to have future articles sent straight to your inbox.

On August 14, a pedestrian named Sammy Davis was struck by a city bus in San Francisco. An ambulance rushed Davis to the hospital, but he was declared dead 20 to 30 minutes after arrival.

Davis’s death didn’t attract much attention until Forbes’s Cyrus Farivar obtained an internal memo from the San Francisco Fire Department blaming two stalled Cruise driverless vehicles for delaying the ambulance.

Farivar’s story led to a flurry of local and national coverage suggesting that Cruise contributed to Davis’s death. Cruise strongly disputed this, arguing that its vehicles hadn’t actually blocked the ambulance at all. The San Francisco Fire Department eventually put out a statement that “the San Francisco Fire Chief has not attributed this pedestrian death to Cruise AVs.”

Based on my reporting, I think it’s unlikely that Cruise contributed to Davis’s death. I spoke to two emergency physicians who told me that a one-minute delay would be unlikely to make a difference for a victim as badly hurt as Davis—though we’ll never know for sure.

What is clear is that Cruise—and its main rival, Waymo—could do a better job handling emergency situations like this. The memo about Davis’s deadly crash was one of dozens that Farivar obtained via an open-records request and published online. These memos document at least 68 times self-driving cars in San Francisco interfered with first responders or otherwise behaved in ways that emergency workers found disconcerting.

According to SFFD records, several Waymo or Cruise vehicles blocked narrow roads, forcing fire trucks to take detours en route to fires. AVs got stuck near firefighting operations, forcing firefighters to work around them as they positioned hoses and ladders. A few AVs parked in front of fire stations, trapping fire trucks inside. A couple of Cruise vehicles drove over firefighters’ hoses.

In my last article, I argued that Cruise and (especially) Waymo have cautious driving styles that help to minimize their chances of crashing into other vehicles. A point I didn’t emphasize enough is that it’s possible to create a dangerous situation by being too timid. Sometimes that’s slamming on the brakes unexpectedly and getting rear-ended. Other times, it’s being frozen with indecision for so long that you impede the work of firefighters or paramedics.

I think these are serious concerns that AV companies—especially Cruise—need to work harder to address. But my reporting on this issue over the last two weeks hasn’t changed my basically positive outlook toward driverless taxis. After all, it was a human-driven bus, not a robotaxi, that struck Davis. And self-driving technology has the potential to save a lot of lives in the long run.

It’s not always safe to stop

A company creating a driverless car faces a chicken-and-egg problem. It doesn’t want to release its vehicle on public streets until it can safely handle every situation it might encounter. But the real world has a “long tail” of tricky situations that are difficult to anticipate in advance.

One way Waymo and Cruise deal with this is by defaulting to inaction. If a driverless vehicle isn’t sure it understands its current situation, it will come to a stop and await instructions from headquarters. Can that be that annoying to other drivers? Sure. But the vast majority of the time it’s not a big deal.

Occasionally it is a big deal though. For example, back in July Cruise reported an incident where one of its vehicles got rear-ended after it slammed on its brakes to avoid hitting a bag blowing in the wind. The other vehicle was probably at fault, legally speaking. But the crash wouldn’t have happened if Cruise had handled the situation more gracefully.

A video from August shows a close call where a Cruise car begins a left turn but then stops abruptly for no apparent reason. Fortunately the driver behind the Cruise car was alert enough to hit the brakes and avert a crash. But it’s easy to imagine this scenario leading to a crash if the rear driver hadn’t been so vigilant.

A bias toward inaction can also cause problems at the scenes of fires, car crashes, and other emergencies. Sometimes Waymo or Cruise vehicles seem to get so confused by the chaos in these locations that they stop for minutes at a time.

Take the tragic incident on August 14, for example. It was a human-driven bus—not an AV—that hit Sammy Davis. But three Cruise AVs got caught up in the ensuing traffic jam.

After the crash, a fire truck arrived and blocked the left lanes of the one-way street to protect the crash site. A few minutes later, an ambulance arrived and pulled up behind one of the Cruise cars. I’ve drawn a diagram to depict the situation at this point in time (by this point a third Cruise vehicle had already departed).

The front Cruise car in my diagram drove off before the paramedics loaded the patient into the ambulance. But the rear Cruise car remained frozen in place for around a minute after the patient was loaded into the ambulance. Eventually, the fire truck backed up to give the ambulance room to go around the left side of the stalled Cruise car.

An SFFD memo written shortly after the crash claimed Cruise blocked two lanes. But Cruise showed me video footage contradicting that. There were two stalled Cruise cars, but they were actually in the same lane, one in front of the other. Other cars were able to squeeze by in the right lane the whole time.

Cruise argues that the ambulance carrying Davis could have taken this same route. I’m not sure about that—the lane might have been too narrow. But either way, I think it’s hard to dispute that the Cruise vehicles handled the situation poorly.

The rear Cruise vehicle was stuck in place for more than six minutes. Whether or not Cruise’s vehicles delayed Davis’s return to the hospital, it’s clearly not helpful to have stalled AVs cluttering up an emergency site.

This was not an isolated incident

Forbes’s Cyrus Farivar obtained SFFD reports on more than 60 incidents involving Cruise or Waymo self-driving vehicles since the start of 2023. While some were fairly innocuous—for example, AVs driving through fire scenes inappropriately but not seriously impeding firefighters’ work—there were a number of cases where the vehicles were a real nuisance.

To understand how significant a problem this is, it’s important to think quantitatively: to divide the number of incidents by the total number of miles traveled. In this case, Waymo and Cruise have collectively completed more than 4 million miles on San Francisco roads since the start of 2023.

So while 60 altercations with the SFFD might seem like a lot, it works out to fewer than 1 incident for every 60,000 miles of driving. Obviously Waymo and Cruise AVs encounter ambulances and fire trucks far more often than that, and they behave better the vast majority of the time.

Unfortunately, we don’t have comparable statistics for human drivers. It’s hard to imagine a human driver making exactly the same mistakes Cruise and Waymo have—human drivers don’t tend to get frozen with indecision for minutes at a time. But I talked to two emergency medicine doctors for this story—one in Northern Virginia and the other in New York City. Both said it was fairly common for human drivers to get in the way of ambulances.

“When I think about city streets in New York, there are often delays because ambulances have to get around cars with drivers in them,” said Dr. Colleen Smith, an emergency medicine specialist in New York City.

My guess is that self-driving vehicles are a bigger nuisance to first responders than human-driven ones. But it’s hard to say how big the difference is—or exactly how much these kinds of glitches hinder emergency workers.

Room for improvement

One reason for optimism here is that there are some straightforward steps AV companies can take to avoid these kinds of problems in the future. And at least one major AV company—Waymo—says it is working to implement them.

Last week I asked Darius Luttropp, the deputy chief of operations at SFFD, if the department had ideas for improving interactions between AVs and first responders. He said the department had three specific requests:

A way to take manual control of a stalled vehicle

A way to talk to remote operators without leaning through a car’s window

A way to automatically notify AV companies of emergency locations to avoid

Waymo says that its vehicles already have a capability for manual takeover—it’s described on page 16 of its manual for first responders. The company is experimenting with audio alerts that can be heard outside the vehicle. And Waymo says it already has an emergency notification system in Phoenix and is working to set up a similar system in San Francisco.

Cruise seems to be a bit behind the curve here. When I asked a Cruise representative about the SFFD requests, she didn’t mention any plans for an emergency notification system. The company’s guide for law enforcement does provide a way for first responders to take over a vehicle. But the guide encourages first responders to contact Cruise via a toll-free number “rather than using in-car buttons designed for occupants.”

The problem, Deputy Chief Luttropp told me, is that SFFD doesn’t issue cell phones to first responders and has no plans to do so. “The requirement to use a cell phone is kind of a line for us,” he said.

“We want all these technologies to have microphones and speakers,” Luttropp said, so they can “make direct verbal communication. Ideally the end goal is not having to get into the vehicle or roll down the window.”

So Waymo and—especially—Cruise have some work to do to improve their relationship with emergency responders. But notably, SFFD’s requests do not require any technological breakthroughs. All three of SFFD’s requests seem straightforward if Waymo and Cruise decide to implement them.

Waymo bolsters its safety case

Last week Waymo released new data strengthening the case that their vehicles crash less often than human-driven vehicles. The study was a collaboration between Waymo and reinsurance company Swiss Re, which has access to a comprehensive database of insurance claims. The study compares successful insurance claims against Waymo to those against a typical human driver.

Over 3.8 million miles of driverless operations, Waymo experienced 76 percent fewer property damage claims than a typical human driver. Even more impressive, there wasn’t a single crash where Waymo had to pay a bodily injury claim. A typical human driver causes a bodily injury about once every 1.1 million miles, so we’d expect to see three or four injury claims across 3.8 million miles of human driving.

People almost always report major crashes to their insurance companies, especially when the other party was at fault. So this data is more comprehensive than the data on police-reported crashes I wrote about in my last article. And Phil Koopman, an expert on AV safety at Carnegie Mellon, told me that the main findings of the Waymo study were statistically credible, albeit with some caveats.

The study only counted crashes where Waymo was found at least partially at fault. But it’s conceivable that Waymo’s driving style could increase crashes without Waymo being legally at fault in any of them. The best drivers prevent crashes by anticipating and compensating for the bad behavior of drunk, inexperienced, and distracted drivers. If Waymo did this less than the average driver, it could lead to more crashes without Waymo necessarily being at fault in any particular crash.

Still, Koopman views the study as another data point backing up Waymo’s contention that its vehicles crash less often than human drivers.

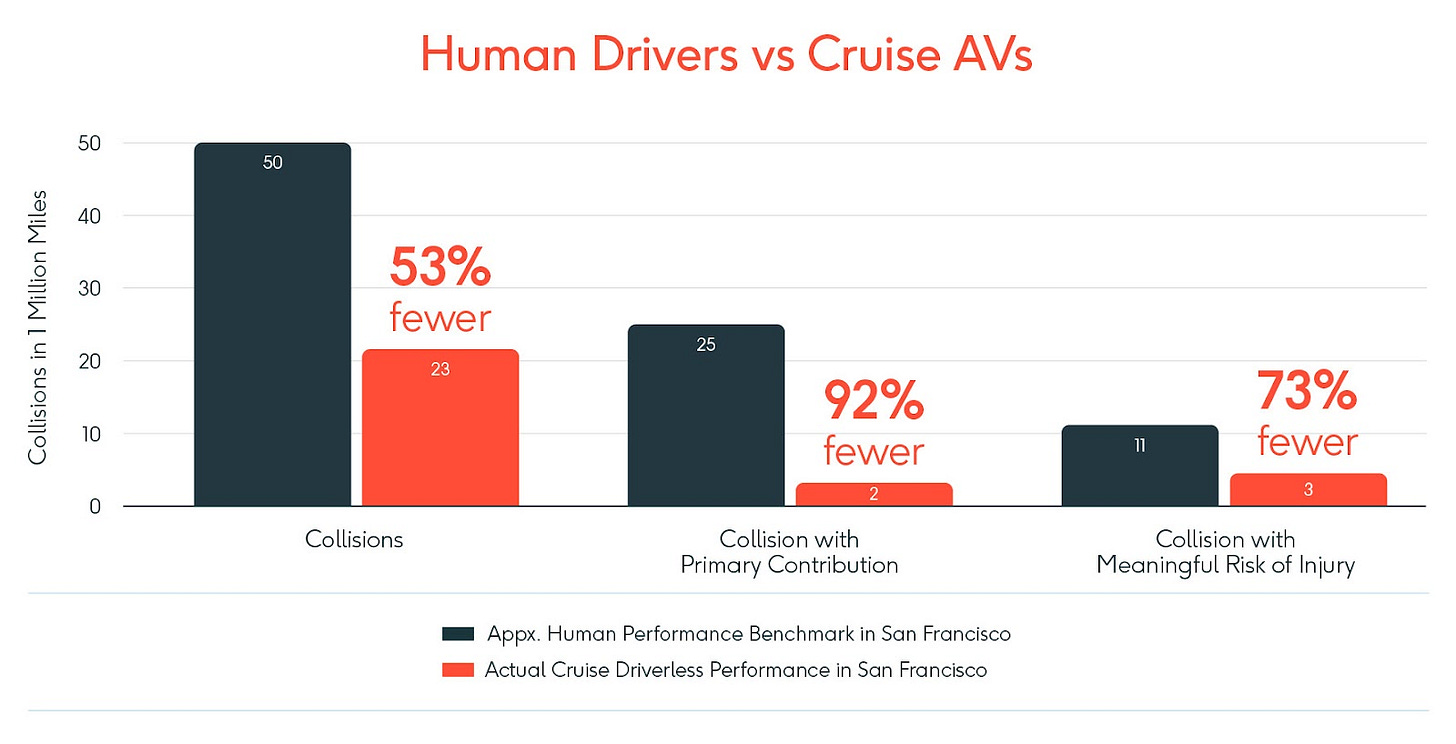

In contrast, Koopman isn’t convinced by the safety data Cruise has published so far. Back in April, Cruise published a report analyzing the company’s first million miles on the road. Here is a key chart from that report:

This looks impressive, but Koopman doesn’t buy it. He noted that “collision with meaningful risk of injury” is not an industry-standard metric and that Cruise has not explained the methodology underlying the human benchmark Cruise is using.

“These metrics are so cherry-picked and the baseline is so opaque, that bar chart means nothing,” Koopman told me.

“What we see from Cruise is a conspicuous display of opacity,” Koopman told me. In contrast, he said, “the Waymo technical guys are being fairly transparent.”

I’ve talked to a number of industry insiders over the last month, and multiple people said they thought the California Department of Motor Vehicles actually did Cruise a favor when it asked Cruise to cut its San Francisco fleet by half on August 18. Cruise needs to continue testing its vehicles on public roads so it can learn from mistakes and get better. But the company seems to have gotten over its skis in recent months.

With half as many cars on the road, Cruise will get half as many negative headlines for mistakes made by its cars. The extra breathing room could give Cruise time to not only hone its technology, but also to streamline its procedures and repair relationships with city officials. Maybe Cruise can even produce some safety statistics that are transparent and rigorous enough to convince skeptics like Koopman.

One interesting thing in the Swiss RE + Waymo paper is that the Testing Operations results (with a safety driver) are still better than the Rider Only results (with no safety driver), particularly for lower-speed (property damage only) collisions. This likely indicates that in the situations where a human decides to take over, they then outperform the AI (just as a human would have taken over and done much better in the emergency situation described in the post). It's not obvious how to leverage that to do better, but it is interesting.

Excellent reporting and analysis! Thank you so much for the effort you put into these in-depth articles.