How consumer demand could limit AI-driven growth

There's a huge difference between automating some jobs and automating all of them.

Some people believe that rapid progress in AI will lead to unprecedented economic growth—perhaps as high as 30 percent annually. At that rate, the world would become 1,000 times wealthier in a generation.

I’m skeptical of predictions like this for a number of reasons. Rapid progress in AI software won’t necessarily translate to rapid progress in robotics. Without much better robots we will continue to need human workers for most tasks. And an AI-powered economy would face various other bottlenecks, from strict building regulations to shortages of key minerals. Aden Barton’s excellent January piece for Understanding AI explored some of these supply-side constraints.

But one of the biggest reasons I doubt we’ll ever see this kind of extreme economic growth is related to demand rather than supply. Even if AI radically increases our capacity to produce goods and services, there are limits to the amount of these goods and services people will want to buy. Indeed, industries with rapid productivity growth often shrink as a share of the overall economy.

The math here is subtle, so rather than clumsily trying to explain it with words, I’m going to illustrate it with an economic fable. I hope this will provide a mathematical intuition for what happens when goods and services get radically cheaper to produce. After the fable I’ll discuss the implications for AI-driven growth.

An economy of shirts and massages

Imagine there’s a remote tropical island where villagers do two kinds of work: weave shirts and give each other massages. It takes 1,000 hours to weave a shirt and 2 hours to give a massage. The average villager works 2,100 hours annually to buy two shirts a year and get one massage a week.

One day foreigners arrive with new weaving machines that improve productivity 10-fold. Now it takes only 100 hours to weave a shirt (massages still take 2 hours). The average villager works a bit less—2,000 hours—but is able to buy 18 shirts per year and get two massages per week.

A generation later, the foreigners return with more advanced weaving machines that allow villagers to produce a shirt in 10 hours. Now the average villager works 1,800 hours to buy 100 shirts a year and get eight massages a week.

This pattern of 10-fold productivity gains continues for two more generations:

The left two columns of this chart show steadily increasing productivity in shirt-making. The time to make a shirt fell from 1,000 hours in the first period to six minutes in the last one. As a result, villagers went from buying two shirts per year to 500.

Yet the share of the economy devoted to the production of shirts is falling. In the first period, shirts accounted for 95 percent of worker time (and hence economic output). By the final period, shirts were just three percent of the economy.

Notice also that GDP growth is declining over time. The first time shirt-making productivity grew tenfold, it yielded 767 percent GDP growth. In the final period, GDP only grew by 27 percent. By this point shirts had become a small share of economic output, so even large gains in shirt-making productivity had a modest impact on economy-wide growth.

Now obviously I made all of these numbers up. If you’re skeptical of my conclusions, I encourage you to make a copy of my spreadsheet and play with the numbers yourself. I think you’ll find that the only assumption that matters is that there’s a limit to how many shirts people want.

If villagers continued devoting 95 percent of their income to shirts—and hence were buying 20,000 shirts annually in the final period—then GDP would have grown at a constant rate. But that’s silly—nobody needs 50 shirts per day.

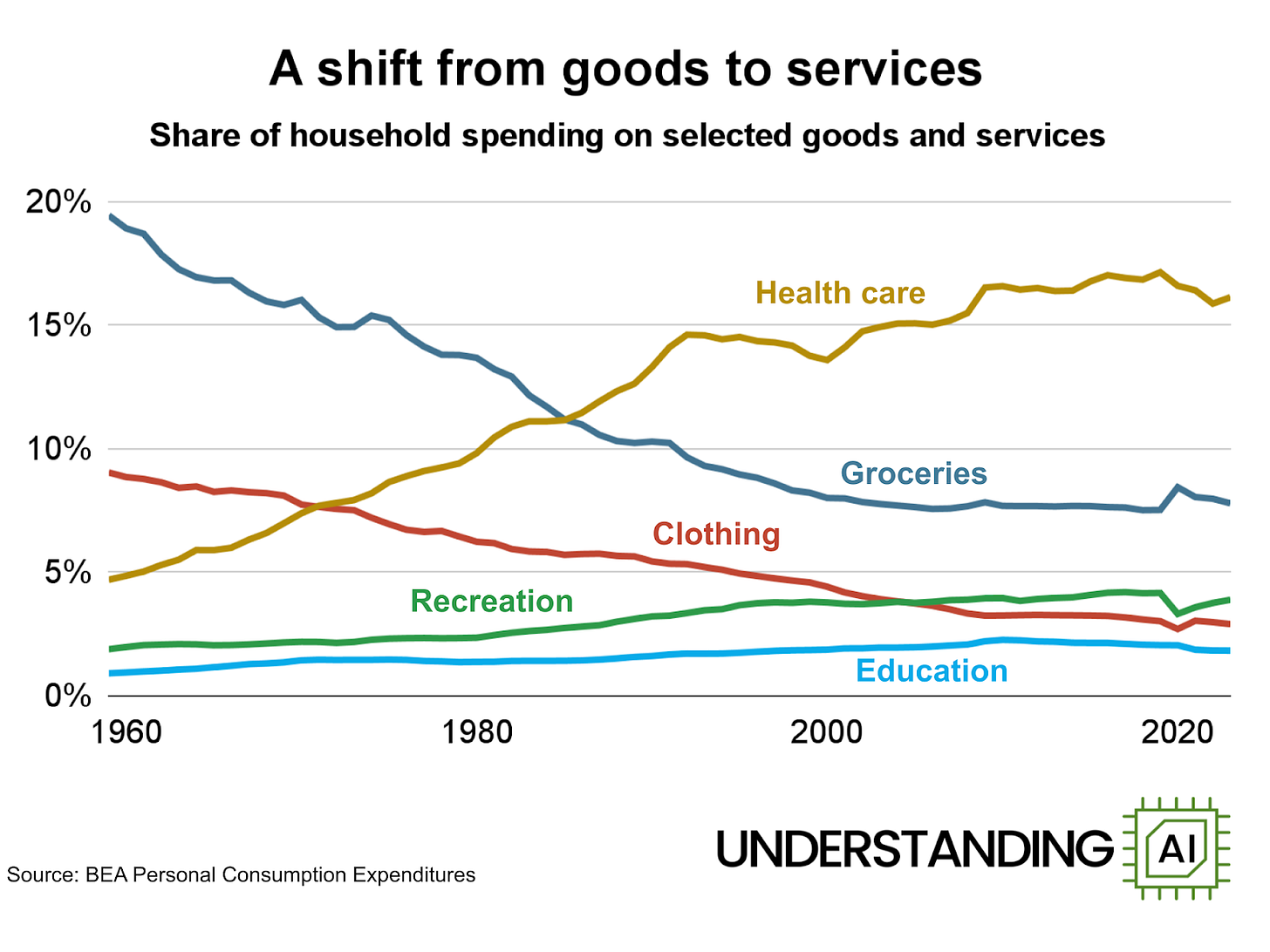

My fable is based on a real historical phenomenon. In 1900, the average household spent 14 percent of its income on clothing. By 1960, it had fallen to 9 percent. Today it’s less than 3 percent.

And this isn’t because we’re buying fewer clothes than we did in 1900—quite the opposite. People are buying more clothing than ever. We (at least in the US) just aren’t increasing our purchases quickly enough to offset falling prices.

So the apparel industry is shrinking as a share of GDP as households shift spending toward goods and services that have not been automated and hence have been getting relatively more expensive—things like education, health care, and recreational services.

Sometimes price cuts spur rapid growth

In 1919 Agatha Christie was a young woman in London expecting her first child. She and her husband hired a maid and a nanny but didn’t own a car.

“Looking back, it seems to me extraordinary that we should have contemplated having both a nurse and a servant,” Christie wrote. “But they were considered essentials of life in those days, and were the last things we would have thought of dispensing with. To have committed the extravagance of a car, for instance, would never have entered our minds. Only the rich had cars.”

This was a period of rapid growth for the fledgling car industry. Henry Ford and other innovators were rapidly reducing automobile prices. In the US, the price of a Model T fell from around $950 in 1910 to less than $400 by 1927. As a result, US automobile sales rose from 181,000 in 1910 to 4.5 million in 1929, a 25-fold increase.

In other words, this is a case where rising productivity—and hence falling prices—led to rapid growth in the overall automobile industry.

In the jargon of economists, demand for cars was highly elastic in the early 20th century. There were lots of people who wanted a car in the 1910s but couldn’t afford one. So as prices fell during the 1920s, a lot of people became first-time car owners.

In recent decades, demand for cars has looked more like demand for clothing: cars have continued to get more affordable, but the share of income we devote to cars has been declining. In 1960, households spent 5.9 percent of their incomes on cars and car parts. In 2023 it was 4.1 percent. Most households today already have one—and often two—cars, so further price cuts don’t stimulate demand the way they did a century ago.

So while demand for cars was highly elastic in 1924, it’s much less so in 2024.

Implications for AI

Some thinkers believe that AI is about to unleash rapid productivity growth in many industries simultaneously. In a recent essay, Leopold Aschenbrenner wrote that “extremely accelerated technological progress, combined with the ability to automate all human labor, could dramatically accelerate economic growth (think: self-replicating robot factories quickly covering all of the Nevada desert).” He acknowledges that “perhaps we’ll want to retain human nannies,” but insists that “we could see economic growth rates of 30%/year and beyond, quite possibly multiple doublings a year.”

I can’t prove that this prediction is wrong, though it sounds pretty unlikely to me. But I want to encourage people thinking about this to take the “perhaps we’ll want to retain human nannies” point seriously. My fable illustrates why this is important.

At the beginning of the fable, massages accounted for only 5 percent of the island economy. But by the final period, massages were 97 percent of economic activity. And this happened not despite the rapid progress in weaving technology but because of it. Society got so good at making shirts that they could provide for everyone’s needs with a tiny share of the island’s labor, freeing up most of the labor for giving massages.

The same basic principle would apply in a world where AI automates 80, 90, or 95 percent of all jobs. In the short term, of course, this would drive a period of rapid economic growth. AI will probably enable the creation of some new products—like delivery robots or new medicines—that initially enjoy rapid growth.

But the process will be inherently self-limiting, just as it has been for cars and textiles. At some point, people will feel they have enough AI-generated goods and services and they’ll use the savings to purchase services like child care that can only be provided by other human beings. And the faster prices fall, the sooner we’ll reach a point of inelastic demand.

I expect AI optimists to resist this comparison. “Sure,” they’ll say, “automating one industry might cause spending to shift toward other industries that are harder to automate. But AI is different because it’s not just going to automate one industry. It’s going to automate every industry simultaneously.”

I don’t see much point in arguing about how quickly any given industry might be automated. But I want to insist that there’s a huge, important difference between automating most jobs and automating all of them. And AI just isn’t going to automate all jobs.

There’s zero chance that parents are going to want robots taking care of their children because young children need to form emotional connections to other human beings. A similar point applies to coaches, therapists, and other jobs where many people are going to prefer a human being over a chatbot or robot.

Precisely because these services are impossible to automate, they are likely to become more, not less, important over time. Any analysis that treats them as an afterthought is going to wind up making bad predictions.

so this argument seems to be more about how high GDP level can get and not growth rates. I find it extremely easy to imagine a world with advanced technology where a typical person is richer than someone making 500k or even 5M per year today, while consuming the same amount of human labor as people today (because they are the typical person). This is granting that robot massages, childcare workers, etc can't replace the human versions. But if you live in a giant house and robots do all your chores and all your home meals are five-star quality with 0 effort (though missing the human touch of a waiter) and you get around in your hypersonic self-flying car, you can be very rich even if your human service consumption is just as constrained as today.

The potential role of automation and intelligence in care work is one of the most intriguing questions out there. A lot people dismiss child care robots; but in truth a lot of child care, and care work in general, is drudgerous, repetitive and sometimes dangerous (home health aides have higher injury rates than police officers). There is a need for emotional connection, and that may require human labor to accomplish. But the actual time and labor involved might be small - a 10 minute check-in every 2 or 3 hours. Think of the time you spend with your child at the playground: mostly you're looking at your phone or chatting with other parents. I think there's probably a lot of scope for automation in care work, if only to focus care workers' time on the social and emotional aspects of care and leave the boring stuff to robots and computers.