Johansson's beef with OpenAI points to unclear laws on voice cloning

No one is sure if it's legal to reproduce a celebrity's voice without permission.

Last September, users gained the ability to speak to ChatGPT using one of five voices dubbed Breeze, Cove, Ember, Juniper, and Sky. Then earlier this month, OpenAI announced a new model, GPT-4o, that could understand the user’s tone of voice and vary its own tone in response. Due out in the coming weeks, this feature should enable more lifelike conversations.

That May 13 announcement prompted comparisons to Her, the 2013 movie about a lifelike digital assistant voiced by Scarlett Johansson. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman invited the comparison when he tweeted the word “her” on the same day.

A week later, Scarlett Johansson released a statement implying that OpenAI had introduced the “Sky” voice at the GPT-4o event (it was actually released in September) and accusing the company of basing Sky on her voice.

OpenAI denied it.

“The voice of Sky is not Scarlett Johansson's, and it was never intended to resemble hers,” Altman said in a statement last week. “We cast the voice actor behind Sky’s voice before any outreach to Ms. Johansson. Out of respect for Ms. Johansson, we have paused using Sky’s voice in our products.”

There’s no question that OpenAI wanted to use Johansson’s voice; the company twice approached her about the idea.

But according to documentation OpenAI shared with the Washington Post, Sky is the voice of a different actress. OpenAI hired her last June, months before it first approached Johansson. And the other woman’s agent told the Washington Post that OpenAI never mentioned Johansson or the movie Her while they were creating the Sky voice.

OpenAI’s decision to stop using Sky means there’s unlikely to be a legal battle between Johansson and OpenAI. But the controversy made me wonder about the state of the law here. This won’t be the last time a company is accused of using a famous person’s voice—and, perhaps, face or other identifying details—in an AI product.

To help me understand the legal landscape, I talked to Eric E. Johnson, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma and an authority on this area of law.

“Very convoluted”

As longtime readers of Understanding AI know, a number of states have passed deepfake laws in the last few years. However, most of these laws have been narrowly focused on two specific deepfake categories: sexually explicit deepfakes and deepfakes designed to influence elections.

So in most states (including California, where OpenAI is based) the main legal protection for people’s voices comes from a common-law concept called the right of publicity. It gives celebrities the right to control the commercial use of their name, voice, and likeness. But Johnson told me that the law here is “very convoluted and very confused.”

Two key rulings out of California helped to establish that celebrities can control the use of their voice in at least some circumstances. In 1988, the federal Ninth Circuit Appeals Court ruled that carmaker Ford had violated Bette Midler’s right of publicity when it broadcast an ad featuring another woman singing one of Midler’s songs. Ford hired one of Midler’s backup singers and coached her to “sound as much as possible like the Bette Midler record.”

In 1992, the same court ruled for Tom Waits in a lawsuit against snack maker Frito-Lay. The company hired an impersonator who imitated Waits’s “raspy, gravelly singing voice.”

Some people have argued that these cases would give Johansson solid grounds for a lawsuit. But two differences could work in OpenAI’s favor in a hypothetical legal fight.

First, Ford and Frito-Lay were openly trying to reproduce the plaintiffs’ voices. In contrast, OpenAI says that Sky’s similarity to Johansson’s voice is coincidental. Maybe contrary evidence would emerge at trial. But if OpenAI is telling the truth, it would undermine Johansson’s case.

Second, the earlier cases both involved advertisements, a quintessentially commercial use of a celebrity’s identity. While ChatGPT is a commercial product in a colloquial sense, Johnson said it’s unclear if courts would classify it that way in a hypothetical right of publicity lawsuit. Courts do not typically consider creative works such as novels, films, or music albums to be commercial even though they are typically produced and sold by for-profit companies. A court could easily reach the same conclusion about OpenAI’s use of the Sky voice.

“If it's just something that comes with the suite of tools with ChatGPT, just because you charge money for them, that doesn't make it commercial,” Johnson told me.

However, two more recent rulings found the right of publicity can apply when a famous person’s identity is used in video games:

The band No Doubt sued Activision for using their identities in the game Band Hero without permission. A California state appeals court ruled for the band in 2012.

College football star Ryan Hart sued Electronic Arts under New Jersey law for making him a character in its game NCAA Football. In 2013, a federal appeals court ruled in Hart’s favor. Another group of college football players won a similar victory under California law later that same year.

We can expect these rulings to figure prominently in future legal battles over the use of a celebrity’s voice, face, and other identifying characteristics in AI products.

There probably won’t be a voice free-for-all

So it’s not clear if the law in California or most other states gives a celebrity control over the use of her voice in AI products. At the same time, Johnson doesn’t expect a legal free-for-all when it comes to AI reproducing the voices of real people. He expects mainstream tech companies to pay for the use of celebrity voices in their AI products whether or not they are legally required to do so.

Indeed, Johnson says that’s been the pattern in the 30 years since the Midler and Waits decisions. Those rulings did not necessarily set clear boundaries for the use of celebrity voices. But companies making ads have mostly erred on the side of caution, proactively seeking permission in cases where the law is unclear.

OpenAI seems to have taken this same approach, suspending use of the Sky voice rather than risk a lawsuit from Johansson. And it seems likely that other tech companies will have a similar attitude.

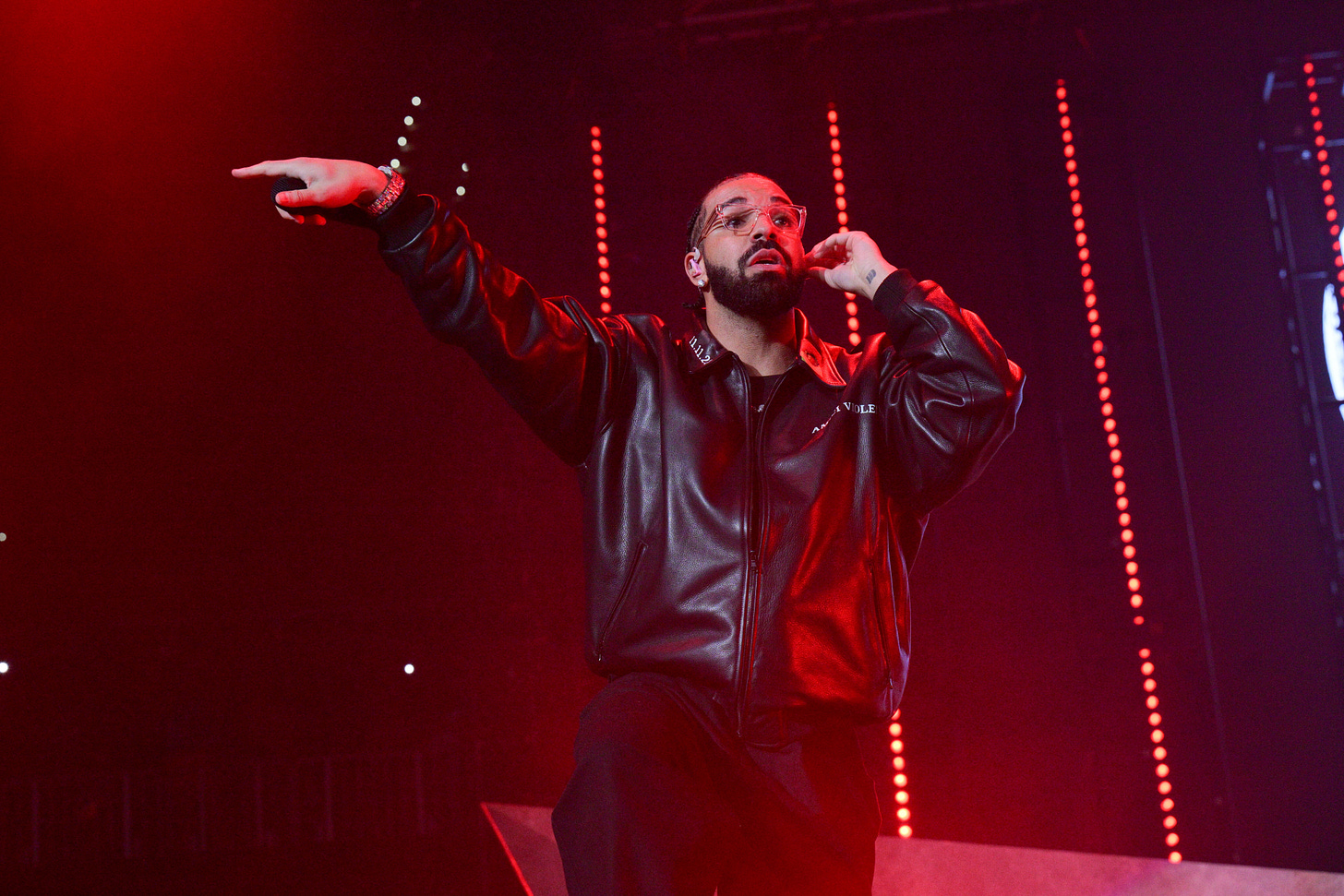

YouTube announced last November that it would take down AI-generated content if it “simulates an identifiable individual, including their face or voice.” YouTube made the announcement a few months after someone released a fake, AI-generated song using the voice of the rapper Drake.

It’s not clear that AI-generated songs like this break any laws. But YouTube has a close relationship with major record labels and seems to be acting voluntarily to help them out.

At some point, of course, someone will test the limits of the law, use AI to reproduce a celebrity’s voice, and get sued. While current case law is murky, Johnson predicts the courts will ultimately interpret the law in ways that prevent unauthorized use of a celebrity’s voice in AI products.

“The common law tends to follow people's intuitions about what's right or wrong,” Johnson told me. If a big company is “perceived as getting something they should have paid for, that's when that sense of justice is most likely to be engaged. I don't think we're likely to be headed toward an era where big companies like OpenAI are just doing anything they want with people's voices.”

Explicit voice protections are coming to Tennessee

So far I’ve focused on California because OpenAI is based on California and because many celebrities live in California. Many states have right of publicity laws that are broadly similar to California’s. And as in California, there’s a lot of uncertainty about how much control celebrities have over the unauthorized use of their voice.

But one state, Tennessee, recently overhauled its right of publicity law to give people explicit and broad control over the use of their voice. Previously, Tennessee’s right of publicity law prohibited the use of someone’s likeness “for purposes of advertising products, merchandise, goods, or services.“ The new law, called the ELVIS Act, is not limited to narrowly commercial uses such as advertising. It appears to prohibit almost any unauthorized use of someone’s “voice or likeness.”

Not only that, the Tennessee law prohibits the distribution of an “algorithm, software, tool, or other technology, service, or device, the primary purpose or function of such algorithm, software, tool, or other technology, service, or device is the production of a particular, identifiable individual's photograph, voice, or likeness.“

This new law doesn’t take effect until July 1 and has not been tested in court. I could imagine a legal challenge arguing that its restrictions on non-commercial speech violate the First Amendment.

Tennessee lawmakers tried to address this by exempting the use of a voice for an itemized list of uses such as news, criticism, scholarship, and parody “to the extent such use is protected by the First Amendment.”

If the law is upheld in court, it could be a big deal. Most celebrities, consumers, and technology companies don’t live in Tennessee, of course. But most popular AI product are likely to be offered for sale in Tennessee, and that could expose technology companies to lawsuits if they use AI to clone someone’s voice. And so the law could effectively set a nationwide standard.

On the specific case of OpenAI and Johansson, it's worth listening to back-to-back comparisons to judge for yourself whether Sky actually sounds like Johansson. Here are two examples:

- https://v.redd.it/qphc92w26p1d1

- https://www.reddit.com/r/singularity/comments/1cx1np4/voice_comparison_between_gpt4o_and_scarlett/

To my ear, they sound distinctly different.

The F/A-18 Mission computer incorporated speech in 1980. Digitized from a real voice. With audio cues like "Pull Up" when too close to the ground. Years later, pilots who had been saved by the gentle female voice wanted to know the name of the woman behind the voice. We tried to figure it out, but Gene Adams, the inventor, had passed away by then. Not sure we ever did get to the bottom of it.