States are racing ahead of Congress to regulate deepfakes

Several states just banned deepfakes in political ads and porn.

I’m excited to publish this guest post by Charlie Guo, author of the excellent Substack newsletter Artificial Ignorance and co-host of Monday’s reader meetup in San Francisco.

If you like Understanding AI, I bet you’ll like Artificial Ignorance as well. Charlie has a degree in computer science from Stanford and is an alum of Y Combinator—so he has serious technology chops. But as you’ll see in this post, he also knows a lot about the policy issues raised by AI. My favorite part of his newsletter is the Friday roundup, where he guides readers through three of the week’s biggest AI stories. Subscribe to his newsletter here.

Last week, the EU passed its flagship AI Act, a sweeping set of regulations that cover not only AI's usage, but also its testing and development. Here in the US, it's a bit of a different story. While plenty of legislation has been proposed, not much has actually been signed into law at the federal level. The White House has tried to close that gap via Executive Order, but there's only so much the president can do without congressional action.

But states are forging ahead with their own laws on AI. And they're focused on one use case in particular: deepfakes.

It's easy to understand why: over the past year, deepfakes have been at the center of a growing number of fraud and abuse cases. The highest-profile example came in January, when Twitter (now X) was bombarded with AI-generated porn of Taylor Swift. But there have been others, like when AI Tom Hanks was promoting dental scams, or when 4Chan created audio of Emma Watson's voice reading Mein Kampf. There are also victims that aren't rich or famous—families have sent money to scammers impersonating loved ones with cloned voices.

So let's take a look at what states are doing to protect constituents today, and what the federal government is working on implementing for tomorrow.

At least 15 states now have deepfake laws

While deepfakes have captured the public's imagination over the past year, they've actually been around for quite a while. The term "deepfake'' was coined in 2017 by Reddit users sharing synthetic videos online. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they were focused on pornography at first: face-swapping celebrity faces onto porn performers’ bodies. But other use cases quickly emerged: in 2018, a deepfake video of Barack Obama disparaging Donald Trump went viral, in an illustration of the dangers of the technology.

According to this excellent website from the government affairs firm Multistate, at least 15 states have passed laws concerning deepfakes, with more on the way. Some of these laws have been around since 2019, but thirteen of those fifteen states have passed new statutes in just the last year. And virtually all of the laws focus on two applications of deepfake technology: politics and pornography.

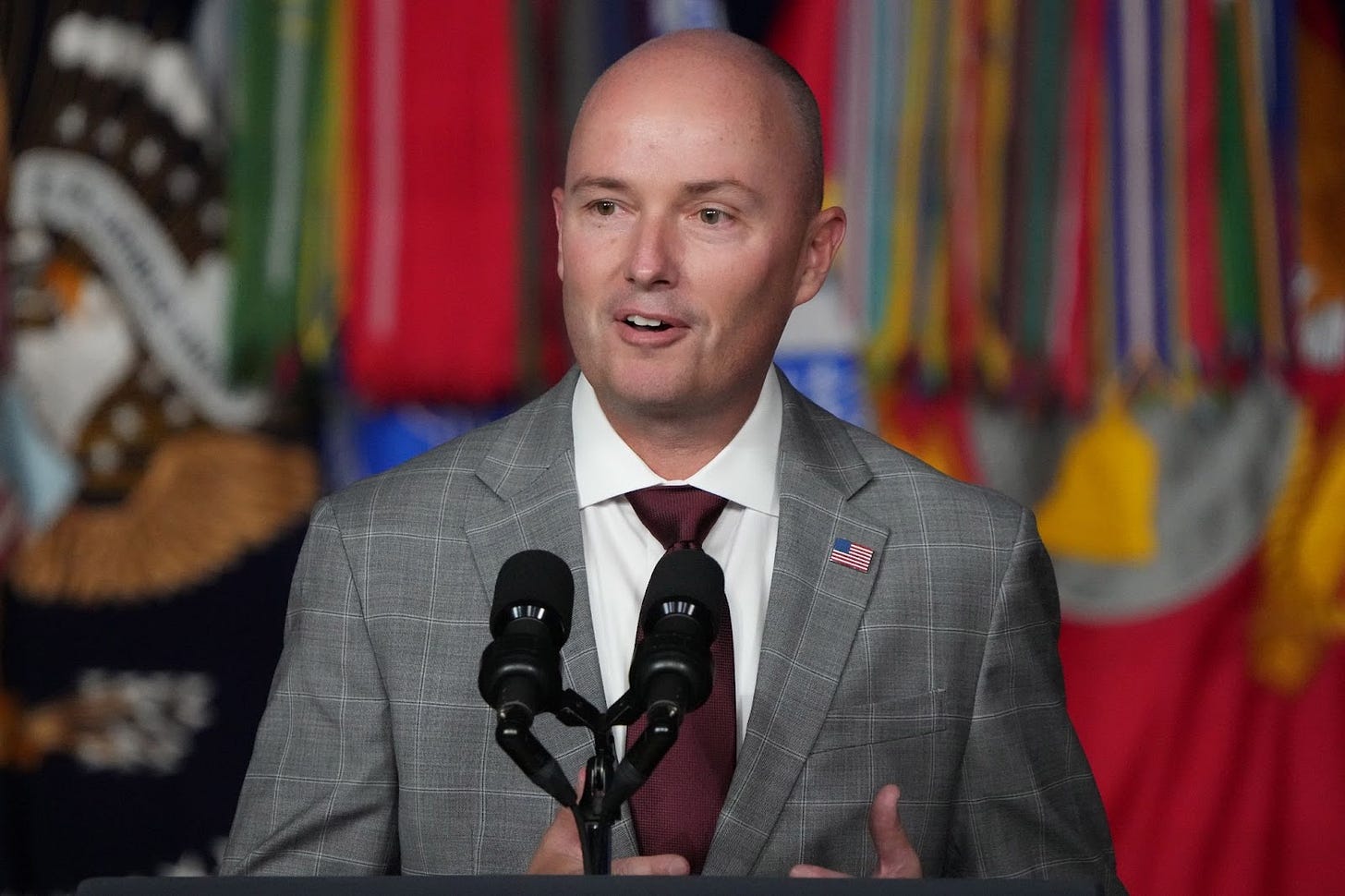

On the politics side, states are concerned about the use of deepfakes in elections and political campaigns. Texas, which passed one of the earliest laws, made it a crime to create and publish deceptive deepfake videos within 30 days of an election. Some states, like Michigan and Minnesota, have extended that window to 90 days. Other states like California and Utah require that political deepfakes be labeled but don’t ban them outright.

States that have passed laws prohibiting, or requiring disclosure of, election-related deepfakes:

California (2019 and 2022)

Indiana (2024)

Michigan (2023)

Minnesota (2023)

New Mexico (2024)

Texas (2019)

Utah (2024)

Washington (2023)

Deepfake pornography laws—often using the phrase "sexually explicit image" instead of "pornography"—cover the creation, publishing, and distribution of altered or synthetic media. The language of these laws varies widely, including phrases like "a composite fictitious person depicted in the nude," "digitally altered sexual image," and "artificially generated intimate parts." Some laws provide civil remedies, while others create criminal penalties. Two states (Louisiana and South Dakota) only outlaw the creation of deepfake CSAM (child sexual abuse material).

States that have passed laws banning or regulating sexual deepfakes:

California (2019)

Georgia (2020)

Hawaii (2021)

Illinois (2023)

Indiana (2024)

Louisiana (2023, CSAM only)

Minnesota (2023)

New York (2023)

South Dakota (2024, CSAM only)

Texas (2023)

Utah (2024)

Virginia (2019)

Washington (2024)

These are not comprehensive lists. For example, Tennessee's proposed ELVIS Act seeks to create an entirely new category of banned deepfake content: impersonating musicians and singers. And other states are still considering passing deepfake legislation during the current legislative session.

These laws have some significant limitations. One is that they mostly cover photos and videos—AI voice cloning has only gotten good in the past couple of years, and the laws haven't yet caught up.

But the biggest issue is that state laws cannot be comprehensive by definition: each state law has slightly different language, and many states have no deepfake laws on the books at all. This patchwork implementation leaves a lot of loopholes, and puts the burden on individuals to keep up with the latest laws in their state.

Which is why Congress is trying to pass federal deepfake legislation that would create a standard across all fifty states. It's difficult to say whether it will succeed; there isn't much bipartisan support for anything these days. But there are a few different approaches being considered in Congress.

Proposed deepfake regulation at the federal level

Today, federal lawmakers are proposing to target deepfake porn with the DEFIANCE Act. The bill, specifically focused on sexually-explicit images, would create a legal avenue for victims to pursue damages against the creators and distributors of said content.

But some proposed bills are looking to go much further than deepfake porn, and are looking to create new protections for "likenesses" in general. Existing protections for "likenesses" (which don’t include things like talking or singing) mostly exist at the state level and cover the commercial use of identities—that is, inappropriately using someone's face or image to make money. And while that would cover some of the strange celebrity endorsements we've seen, it's a fairly narrow protection in the age of deepfakes.

New legislation would attempt to change some of the limitations of our current approach. The NO FAKES Act and No AI Fraud Act are two very similar bills (in the Senate and House, respectively) that would create a federal right of publicity for all individuals, both famous and obscure. In both cases, people would have the ability to file civil lawsuits against those who create and distribute unauthorized deepfakes for any reason, not just commercial activity. In particular, the No AI Fraud Act sets minimum damages at $5,000 for each unauthorized publication.

While there are some First Amendment exceptions, the laws add some additional risks to hosting content—meaning that AI tools and social media platforms would become responsible for ensuring unauthorized AI deepfakes are somehow blocked. But it's unclear how social media platforms would identify said AI-generated content—especially given that there are no reliable methods of detecting deepfake content for domains such as text. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has pointed out that making platforms liable for hosting deepfake content could create a chilling effect:

Many of these services won’t be in a good position to know whether AI was involved in the generation of a video clip, song, etc., nor will they have the resources to pay lawyers to fight back against improper claims. The best way for them to avoid that liability would be to aggressively filter user-generated content, or refuse to support it at all.

Other bills could make that easier—the AI Labeling Act would require clear labels on any AI-made content. However, it's still hard to say whether or not these laws are too broad, as there are clearly valid First Amendment use cases for using someone's likeness, including news, protests, and parody.

Finding the right balance

Part of what makes broad regulation of deepfakes difficult are the First Amendment challenges that come with it. People have been creating altered (some might say "misleading") images for many years, and for the most part it’s not illegal to do so. It’s not illegal for me to Photoshop my friend's face onto a meme without his consent, nor is it illegal for me to record myself impersonating a celebrity. Banning people from doing these same things using AI technology would significantly restrict people’s freedom of speech.

Crafting deepfake laws targeting specific use cases—like pornography or political advertising—gives more room for nuance and context. Some use cases, like parody or creative expression, seem socially beneficial. Others, like having an AI movie star make offensive remarks or cloning an ex-girlfriend to create AI voice messages, seem more sinister. And we can look at where we have existing laws banning media manipulation and misinformation—at the application, not technology, level. There are plenty of cases where blatant misrepresentation is illegal—you can't do it in a political ad, an investment prospectus, or a courtroom.

I don't envy legislators here—it's going to be incredibly difficult to strike the right balance. Too narrow, and you won't meaningfully change the incentives for AI deepfakes. Too broad, and you risk stifling creative expression and limiting legitimate speech.

Moreover, enforcing these laws won’t be easy. It was one thing when only a handful of companies had the ability to wield deepfake technology. Now, anyone with a GPU and a few days to learn the ropes can create celebrity deepfakes. And when it comes to foundation models like Stable Diffusion, we're not going to put the genie back in the bottle.

Ultimately, we're going to need thoughtful, precise, and practical laws to combat AI fraud and abuse—laws that focus on actual harms rather than speculative ones, and that avoid imposing heavy costs that cannot keep up with the technology's advancement. Given how fast the industry is moving, and how broadly AI is working its way into our daily lives, it's important for lawmakers to get it right.

If you found this article helpful, please subscribe to Charlie’s newsletter.

Legislators can pass all the laws they want, but enforcement is a world away from signing bills into law. Does no-one recall the Volstead act, or the 75+ years of reefer-madness cannabis prohibition? Rotsa ruck, y'all.

What a fascinating topic. My question is: Are these laws enforceable? "The language of these laws varies widely, including phrases like "a composite fictitious person depicted in the nude," "digitally altered sexual image," and "artificially generated intimate parts." Seems incredibly broad. Would Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus" be illegal? Only if done on the computer?