The AI Investment Boom

AI Demand is Driving Skyrocketing US Investment in Computers, Data Centers, and Other Physical Infrastructure

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 45,000 people who read Apricitas!

Last month, Microsoft made a high-profile announcement that it is paying to reopen reactor one at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant to meet the company’s growing data center power demand, joining Amazon as the second major US tech company to turn to legacy nuclear facilities for their increasing energy needs. Microsoft is the primary investor and computing provider for OpenAI, who kicked off a revolution in AI development with its release of ChatGPT less than two years ago—and the Three Mile Island reopening underscored the frenzied growth in physical investment currently going on to meet the demands of these new AI systems.

Today, AI products are used ubiquitously to generate code, text, and images, analyze data, automate tasks, enhance online platforms, and much, much, much more—with usage expected only to increase going forward. Yet these cutting-edge models require enormous computing resources for their training and inference, that computing requires massive arrays of advanced hardware housed at industrial-scale facilities, and those facilities require access to vast quantities of power, water, broadband, and other infrastructure for their operations.

Thus, the downstream result of the AI boom has been a rapid increase in US fixed investment to meet the growth in computing demand, with hundreds of billions of dollars going to high-end computers, data center facilities, power plants, and more. Right now, US data center construction is at a record-high rate of $28.6B a year, up 57% from last year and 114% from only two years ago. For context, that’s roughly as much as America spends on restaurant, bar, and retail store construction combined.

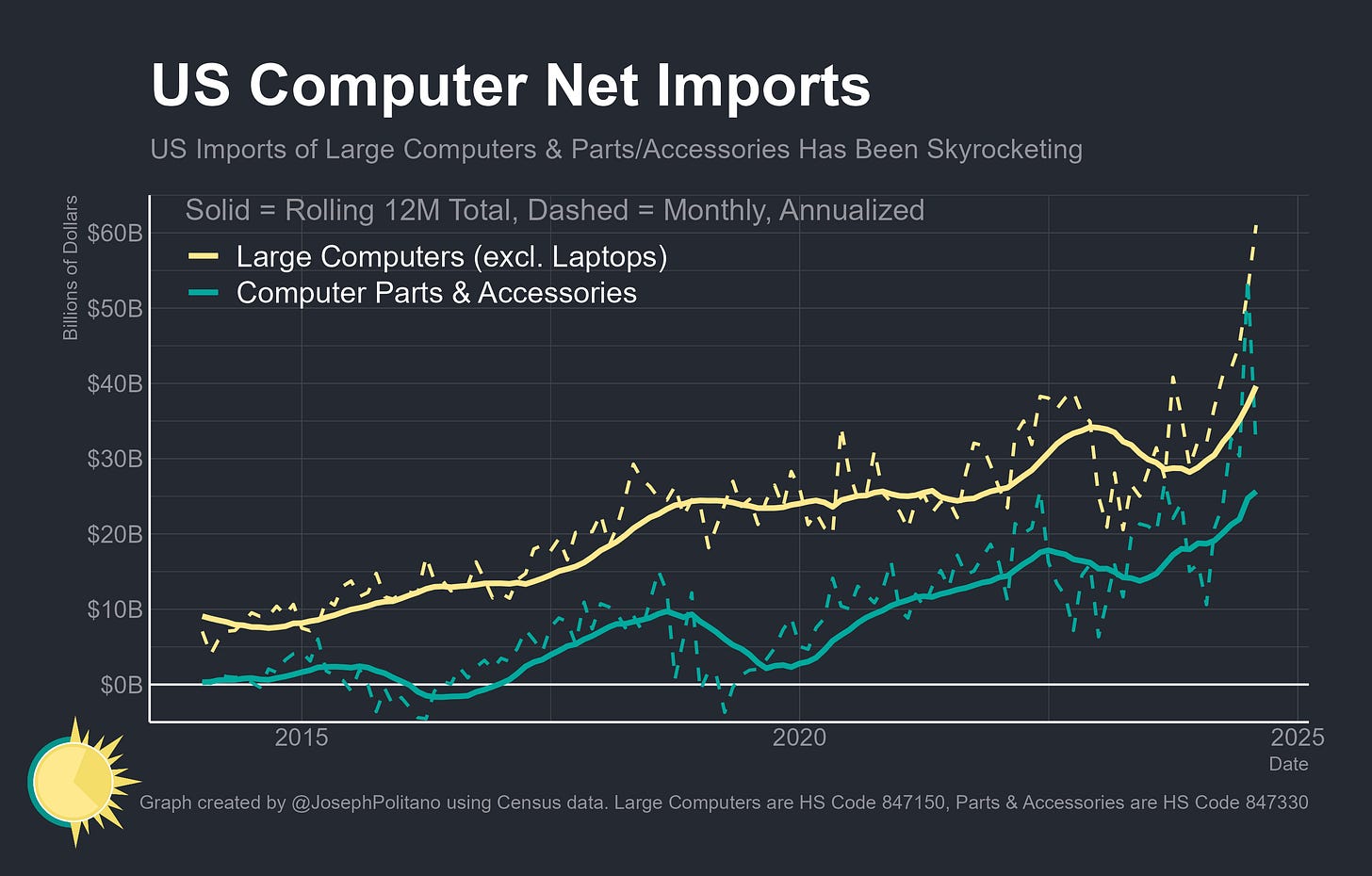

However, that construction figure is only for the physical buildings themselves—it excludes the massive racks of high-powered computers that form the brains of data centers plus the vast quantities of cables, fans, and other parts necessary to make that brain work. In August, net US imports of large computers (like those used for AI training) rose to a new record high, and net imports of computer parts, accessories, and other components had set a record high just the month before—in total, the US has brought in more than $65B across the two categories over the last year on top of rising domestic production.

The majority of these new data centers, computers, and equipment are being bought by companies in the information technology space—that includes computing infrastructure providers like Amazon, web search firms like Google, and software publishers like Microsoft. Those companies have increased their net holdings of property, plant, and equipment by more than $95B over the last year, a record high, as they each compete to rapidly scale up and deploy their AI systems.

It’s a stark change from a little over a decade ago, when Facebook bought up Instagram for only $1.2B, following it up by paying $15B for WhatsApp two years later. At the time, these acquisitions were some of the largest in tech history and marked the beginning of an era where lightweight software publishers were considered the industry’s future—in total, Instagram had only 13 employees at the time it was purchased, Whatsapp had only 55, and neither company had much of a physical presence beyond some office space and programmers’ workstations. Today, Facebook (now Meta) has spent $15.2B on capital expenditures in the first half of 2024 alone, much of it on massive arrays of computing infrastructure to support the company’s Llama brand of AI models. So far, the AI boom has been more hardware-intensive than any tech boom in history, and that is rapidly boosting construction and investment within the United States.

Physical Investment for Digital Minds

American businesses’ investment in computers and related equipment has skyrocketed to a new record high amidst the AI boom, jumping 16.6% over the last year even after adjusting for inflation. That’s in stark contrast to the nearly-decade-long relative stagnation in investment seen throughout the 2010s, which was only really shattered by the digital demands of the pandemic-era remote work boom. Computer investment retracted a bit in 2022 as work-from-home levels and internet usage stabilized, but it then came roaring back with the AI boom starting in late 2023.

Yet not all computers are created equal—total computer investment may be at record levels, but the growth in the highest-end computer systems has been even faster. Taiwan’s TSMC is the world’s leading manufacturer of cutting-edge semiconductors, and the ravenous demand for AI compute is visible in the growing amount of chips, computers, and related components that the US now imports from Taiwan. Those imports have totaled more than $38B over the last year, rising more than 140% over the previous year, with little sign of stopping. All three categories have seen rapid growth, but direct US imports of logic chips have seen the largest relative increase, rising from relatively minimal levels to nearly $5B a year. Computer parts and components remain the largest import item—a reminder that data centers require more than just computers for their day-to-day operation and even when operational require further supplies for their maintenance and repair.

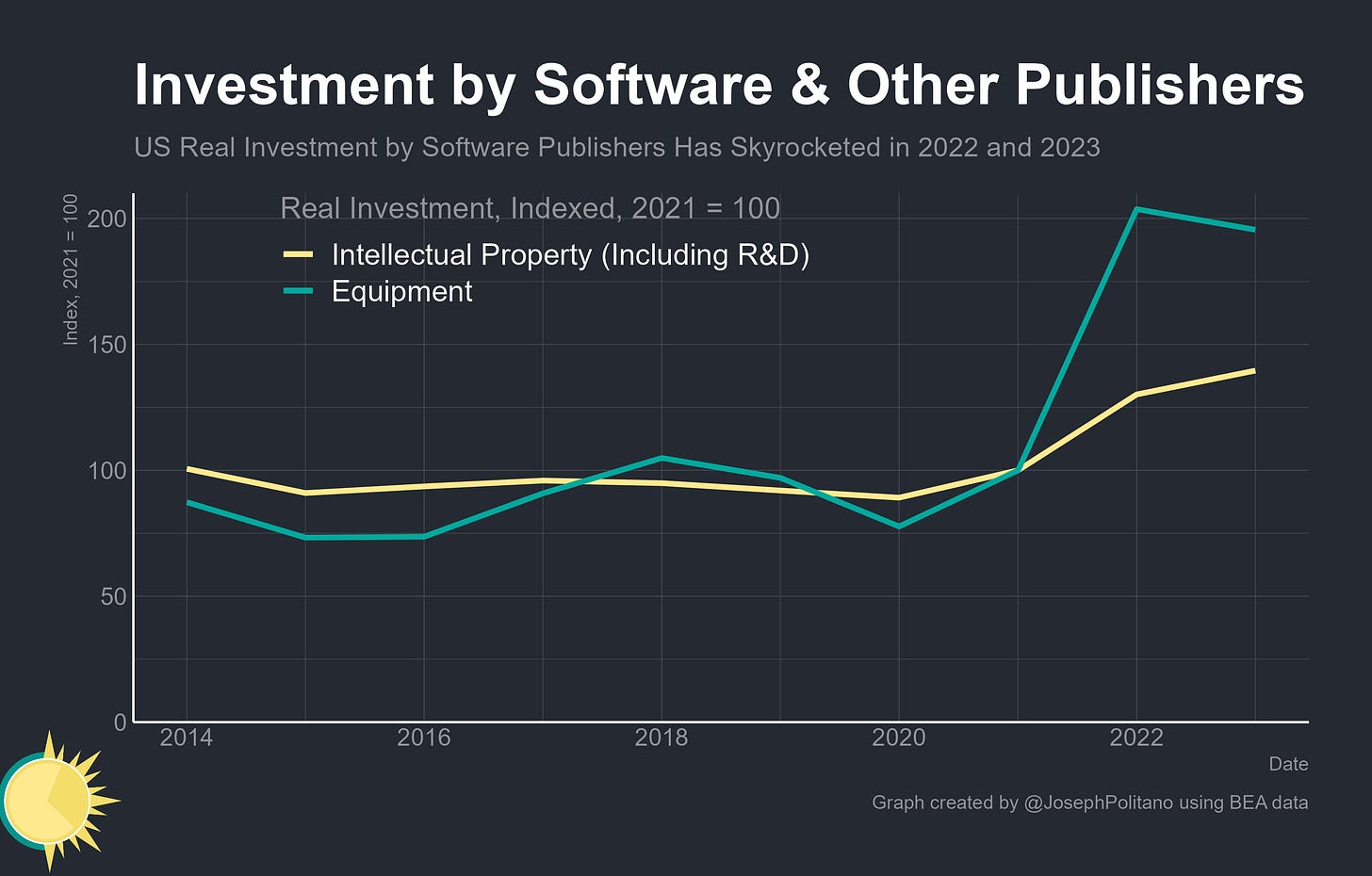

Breaking down the detailed sector-level investment data available through 2023 shows that although data processors and web search firms like Amazon/Google continued to have the largest investment levels in the tech space, it was software developers who saw the fastest investment growth. Software publishers’ real investment in intellectual property—which encompasses many of the AI models themselves plus related research and development—grew by 40% since 2021, while real investment in equipment like computers grew by an astonishing 96%. The era of leading software developers being hardware-light companies has been replaced by an era where developers are racing each other to see who can build out hardware capabilities the fastest.

The Local Cloud

All of this hardware investment is not, however, evenly spread throughout the country. While data centers have to be spread out to some extent in order to serve networking needs and avoid binding infrastructure constraints, it’s often beneficial to concentrate them in large clusters to multiply their effectiveness and reduce costs/latency. That’s especially true for AI, which is why firms are pushing the limits of data center size and networking to throw as much computing power at model development as possible.

While we do not have granular data center construction data—official construction numbers only break down data center spending at the regional level—we can still see some interesting underlying patterns. The US data center buildout has remained strongest in its historical clusters within the American South, but growth has been much faster in markets throughout the Midwest and West Coast, while the Northeast has been functionally unaffected.

That buildout can have large implications for local power demand—over the last few months, the Energy Information Administration has repeatedly raised its projections for load growth based on data center demand, now predicting that total commercial-sector electricity consumption will rise 3% this year and another 1% next year. While those projections still leave commercial users as a smaller driver of rising power consumption than residential electrification and industrial reshoring, they represent the sector’s fastest demand growth in years—for context, commercial power consumption rose only 5% in total between 2007 and 2023 and the pre-AI-boom official estimates put computers & office equipment at only 11.4% of total commercial power consumption.

Yet in some parts of the country, data center power consumption has been a major driver of electricity load growth—to use an illustrative example, North Dakota’s commercial power consumption has risen by more than 45% after the opening of several key data centers in 2022. However, North Dakota is a relatively tiny power and computing market, so the most significant increases in raw power demand have instead come from larger data center clusters in larger states like Virginia and Texas.

The byteway in the Northern Virginia suburbs of DC is the largest cluster of computing power in the world, and it’s caused the state to see a 30% increase in commercial energy consumption since 2019 and the largest raw increase in commercial power demand in the nation. Texas, which has explicitly worked to attract data centers and crypto miners as part of its energy load management program, has also seen a 10% increase in commercial power consumption since 2019, with much larger growth expected in the coming years.

That data center load growth has been a contributor to the Lone Star State’s notable overperformance in renewable investment, where it leads the rest of the country significantly. Indeed, ERCOT (Texas’ power grid) and PJM (which serves Virginia) are both currently projected to outpace the nation in renewables growth through this year and 2025. The agglomeration benefits of data centers mean that AI firms are increasingly looking to concentrate near large power resources, hence the renewed focus on nuclear energy and the growing desire for tech companies to directly invest in power generation infrastructure as they build computing capabilities.

The Long Shadow of the Techcession

Amidst the AI boom, revenue in the information technology space has rebounded from the slowdown of 2022 and 2023—software publishers, web search portals, and computing infrastructure providers have all seen their incomes rise by 12-15% over the last year. It’s a far cry from the halcyon days of 2021, but still puts revenue growth on the strong side of pre-COVID norms.

Yet despite the tech sector’s recent rebound in revenues and boom in physical investment, employment growth has remained remarkably weak. The US has added only 32k tech jobs over the last year, lower than at any point in 2021, 2022, or the 9 years preceding the pandemic. Even the software publishers and computing infrastructure industries at the forefront of this AI boom have seen functionally zero net employment growth over the last year—the dismal job market that has beleaguered recent computer science graduates simply has not improved much.

That’s not to say there’s been no labor market impact of the AI investment boom, but rather that they’ve been primarily outside of traditional information tech sectors. Total compensation in semiconductor manufacturing increased 25% from Q1 2023 to Q1 2024 as workers in companies like NVIDIA got much more valuable stock options. Some of the 30k increase in commercial construction jobs over the last year is certainly downstream of data center demand—that’s in addition to the ongoing job boom in industrial construction for chip fabs and other manufacturing sectors, plus the employment gains as part of the electricity power and broader infrastructure buildout. Yet so far, the job dynamics of the AI boom have been radically different than the past decade of tech labor markets as growth focuses more on hardware investments, manufacturing/design firms, and infrastructure builders more than traditional programmers.

Conclusions

Right now, AI developers are competing intensely and each banking that continued product improvements and greater commercialization will more than validate the historical scale of current investments. In the near term, investment is only expected to increase as more advanced models are developed and AI usage is expanded into more real-world applications (like self-driving vehicles). Policymakers also view AI as a key part of the future US economy—AI development and data center capacity are cutting-edge industries where America has built a significant lead by virtue of the dominance of Silicon Valley and large US tech conglomerates, and thus the AI boom has benefitted US investment more than perhaps any other country.

Yet that makes it more likely geopolitical competition will intensify around hardware capacity—the CHIPS Act that is driving so much of current US electronics industrial policy was a pre-ChatGPT creation, and some industry heads already complain that it’s showing its age in terms of priorities and scale. The significant increase in demand for high-end semiconductors has boosted US reliance on Taiwanese imports, which the CHIPS Act was supposed to help ameliorate, and there are any number of components where the US remains dependent on China to meet data-center-scale supply. Plus, the US will likely continue restricting Chinese access to the highest-end chips in hopes of holding back their AI development, while China continues to build out its chipmaking capacity in hopes of reducing import dependence. As this AI investment boom continues, expect it to only move further into the forefront of the ongoing Chip War.