An unlikely ally for open-source protein-folding models: Big Pharma

Drug companies are funding open-source AI to avoid depending on Google.

Protein-folding models are the success story in AI for science.

In the late 2010s, researchers from Google DeepMind used machine learning to predict the three-dimensional shape of proteins. AlphaFold 2, announced in 2020, was so good that its creators shared the 2024 Nobel Prize in chemistry with an outside academic.

Yet many academics have had mixed feelings about DeepMind’s advances. In 2018, Mohammed AlQuraishi, then a research fellow at Harvard, wrote a widely read blog post reporting on a “broad sense of existential angst” among protein-folding researchers.

The first version of AlphaFold had just won CASP13, a prominent protein-folding competition. AlQuraishi wrote that he and his fellow academics worried about “whether protein structure prediction as an academic field has a future, or whether like many parts of machine learning, the best research will from here on out get done in industrial labs, with mere breadcrumbs left for academic groups.”

Industrial labs are less likely to share their findings fully or investigate questions without immediate commercial applications. Without academic work, the next generation of insights might end up siloed in a handful of companies, which could slow down progress for the entire field.

These concerns were borne out in the 2024 release of AlphaFold 3, which initially kept the model weights confidential. Today, scientists can download the weights for certain non-commercial uses “at Google DeepMind’s sole discretion.” Pushmeet Kohli, DeepMind’s head of AI science, told Nature that DeepMind had to balance making the model “accessible” and impactful for scientists against Alphabet’s desire to “pursue commercial drug discovery” via an Alphabet subsidiary, Isomorphic Labs.

AlQuraishi went on to become a professor at Columbia, and he has fought to keep academic researchers in the game. In 2021, he co-founded a project called OpenFold, which sought to replicate AlphaFold’s innovations openly. This not only required difficult technical work, it also required innovations in organization and fundraising.

To get the millions of dollars’ worth of computing power they would need, AlQuraishi and his colleagues turned to an unlikely ally: the pharmaceutical industry. Drug companies are not generally known for their commitment to open science, but they really did not want to be dependent on Google.

Supporting OpenFold gives these drug companies input into the project’s research priorities. Pharmaceutical companies also get early access to OpenFold’s models for internal use. But crucially, OpenFold releases its models to the general public, along with full training data, source code, and other materials that have not been included in recent AlphaFold releases.

“I’d like to see the work have an impact,” AlQuraishi told me in a Monday interview. He wanted to contribute to new discoveries and the creation of new therapies. Today, he said, “most of that is happening in industry.” But projects like OpenFold could help carve out a larger role for academic researchers, accelerating the pace of scientific discovery in the process.

Protein folding: from sequence to structure

Proteins are large molecules essential to life. They perform many biological functions, from regulating blood sugar (like insulin) to acting as antibodies.

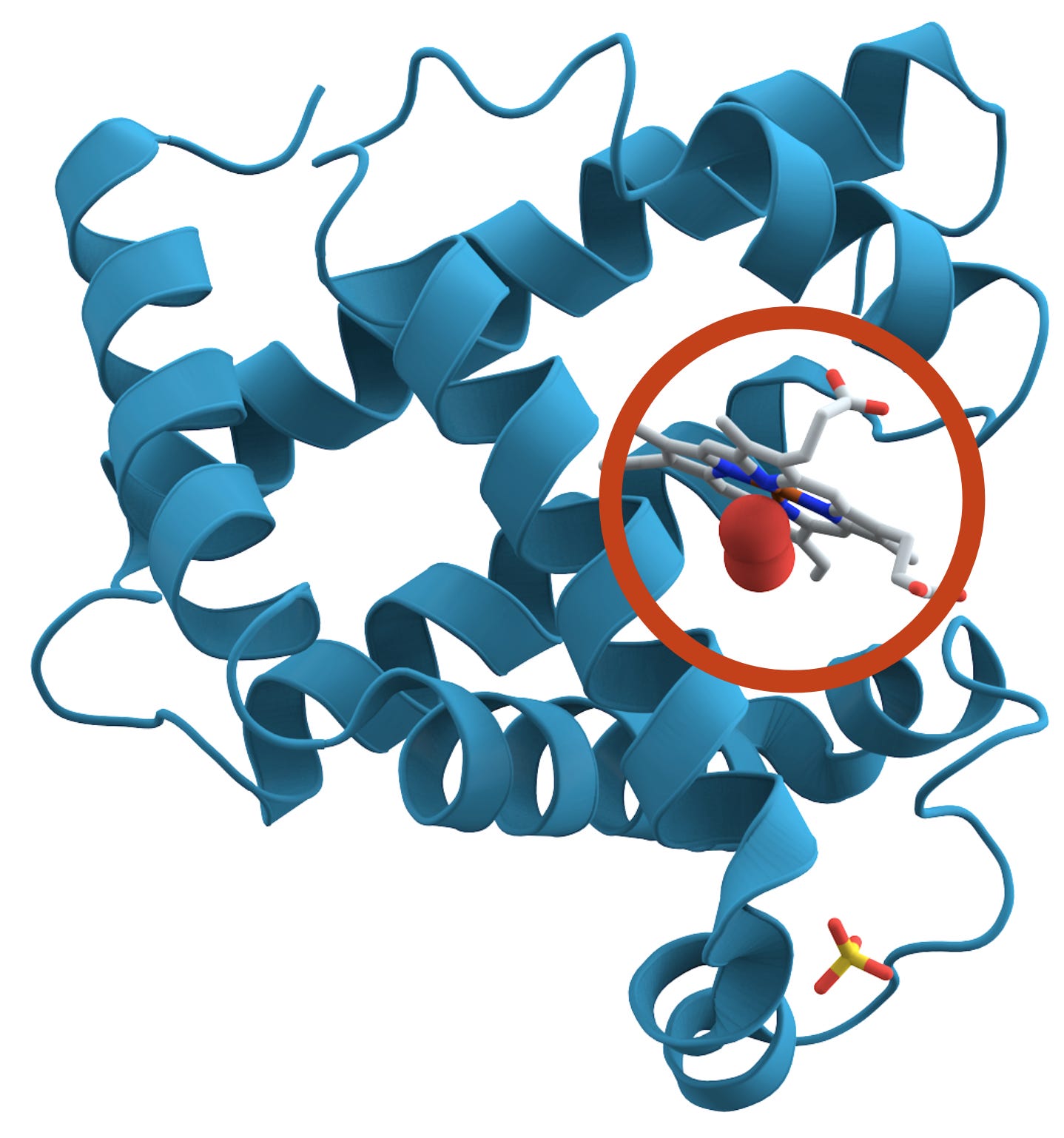

The shape of a protein is essential to its function. Take the example of myoglobin (pictured), which stores oxygen in muscle tissue. Myoglobin’s shape creates a little pocket that holds an iron-containing molecule (the grey shape circled). The pocket’s shape lets the iron bind with oxygen reversibly, so the protein can capture and release it in the muscle as necessary.

It’s expensive to determine a protein’s shape experimentally, however. The conventional approach involves crystallizing the protein and then analyzing how X-rays scatter off the crystal structure. This process, called X-ray crystallography, can take months or even years for difficult proteins. Newer methods can be faster, but they’re still expensive.

So scientists often try to predict a protein’s structure computationally. Every protein is a chain of amino acids — just 20 types — that fold into a 3D shape. Determining a protein’s amino acid chain is “very easy” compared to figuring out the structure directly, said Claus Wilke, a professor of biology at The University of Texas at Austin.

But the process of predicting a 3D structure from the amino acids — figuring out how the protein folds — isn’t straightforward. There are so many possibilities that a brute-force search would take longer than the age of the universe.

Scientists have long used tricks to make the problem easier. For instance, they can compare a sequence with the 200,000 or so structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Similar sequences are likely to have similar shapes. But finding an accurate, convenient prediction method remained an open question for over 50 years.

This changed with AlphaFold 2, which made it dramatically easier to predict protein structures. It didn’t “solve” protein folding per se — the predictions aren’t always accurate, for one — but it was a substantial advance. A 2022 Nature article reported that 80% of 214 million protein structure predictions were accurate enough to be useful for at least some applications, according to the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI).

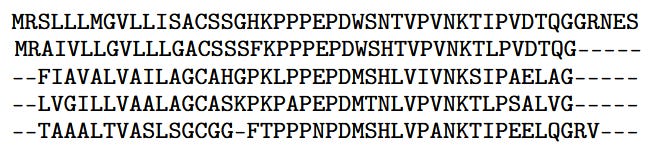

AlphaFold 2 combined excellent engineering with several clever scientific ideas. One important technique DeepMind used is called coevolution. The basic idea is to compare the target protein with proteins that have closely related sequences. A key step is to compute a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) — a grid of protein sequences organized so that equivalent amino acids are in the same column. Including an MSA in AlphaFold’s input helped it to infer details about the protein’s structure.

The original OpenFold

DeepMind released AlphaFold 2’s model weights and a high-level description of the architecture but did not include the training code or all the training data used. OpenFold, founded in 2021, sought to make this kind of information freely available.

AlQuraishi’s background prepared him well to co-found the project. He grew up in Baghdad as a computer kid — starting with a Commodore 64 at the age of five. When he was 12, his family moved to the Bay Area. He founded an Internet start-up in his junior year of high school and went to Santa Clara University for computer engineering.

In college, AlQuraishi’s interests shifted from tech entrepreneurship to science. After a year and a half of working to add computational biology capabilities to the software Wolfram Mathematica, he went to Stanford to get his doctorate in biology. After his PhD, he went on to study the application of machine learning to the protein-folding problem.

After the first AlphaFold won the CASP13 competition in 2018, AlQuraishi wrote that DeepMind’s success “presents a serious indictment of academic science.” Despite academics outnumbering DeepMind’s team by an order of magnitude, they had been scooped by a tech company new to the field.

AlQuraishi believed that tackling big problems like protein folding would require an organizational rethink. Academic labs traditionally consist of a senior scientist supervising a handful of graduate students. AlQuraishi worried that small organizations like this wouldn’t have the manpower or financial resources to tackle a big problem like protein folding.

“I haven’t been too shy about trying new ways of organizing academic research,” AlQuraishi told me on Monday.

AlQuraishi thought that academic labs needed more frequent communication and better software engineering. They would also need substantial access to compute: when Geoff Hinton joined Google in 2013, AlQuraishi predicted that “without access to significant computing power, academic machine learning research will find it increasingly difficult to stay relevant.”

So in 2021, AlQuraishi teamed up with Nazim Bouatta and Gustaf Ahdritz to co-found the OpenFold project. The project didn’t just have an ambitious technical mission, it would also come to have an innovative structure.

OpenFold’s first objective was to reverse-engineer parts of AlphaFold 2 that DeepMind had not made public — including code and data used for training the model. While DeepMind had only drawn from public datasets in its training process, it did not release the multiple sequence alignment (MSA) data it had computed for use in training. MSAs are expensive to compute, so many other research groups settled for fine-tuning AlphaFold 2 rather than retraining it from scratch. OpenFold released both a public dataset of MSAs — using four million hours of donated compute — and training code.

The second goal was refactoring AlphaFold 2’s code to be more performant, modular, and easy to use. AlphaFold 2 was written in JAX — Google’s machine learning framework — rather than the more popular PyTorch. OpenFold wrote its code in PyTorch, which boosted performance and made it easier to adopt into other projects. Meta used parts of OpenFold’s architecture in its ESM-Fold project, for instance.

A third goal — true to AlQuraishi’s computer science background — was to study the models themselves. In their preprint, the OpenFold team analyzed the training dynamics of AlphaFold’s architecture. They found, for instance, that the model reached 90% of its final accuracy in the first 3% of training time.

Finally, AlQuraishi and his collaborators wanted to make sure there was a protein-folding model that pharmaceutical companies could use. They saw this as necessary because AlphaFold 2 was initially released under a non-commercial license. But this goal became irrelevant after AlphaFold 2’s license was changed to be more open.

The OpenFold team had made substantial progress on all of these goals by June 22, 2022, when it announced the release of OpenFold and the first 400,000 proteins in its MSA dataset. There was more refinement to be done — the preprint wouldn’t come out for another five months; the model code would continue to be iterated on — but OpenFold also had other scientific goals. AlphaFold 2 initially only predicted the structure of a single amino acid chain; could OpenFold replicate later efforts to predict more complex structures?

So the same day, OpenFold also announced that pharmaceutical companies — who are also interested in the same types of protein folding questions — would help fund OpenFold’s further research in exchange for input into its research direction.

The race to replicate AlphaFold 3

The peer-review process is so slow that the official OpenFold paper was published by Nature Methods in May 2024 — a year and a half after the initial release. A week before the paper came out, Google DeepMind incidentally demonstrated the value of open research.

DeepMind announced AlphaFold 3, which was able to predict how interactions with other types of molecules would impact the 3D shapes of proteins. But there was a caveat: the model would not be released openly. DeepMind had partnered with Isomorphic — Google’s AI drug discovery start-up that Hassabis founded in 2021 — to develop AlphaFold 3. Isomorphic would get full access and the right to commercial use; everyone else would have to use the model through a web interface.

Scientists were furious. Over 1,000 signed an open letter attacking the journal Nature for letting DeepMind publish a paper on AlphaFold 3 without providing more details about the model. The letter remarked that “the amount of disclosure in the AlphaFold 3 publication is appropriate for an announcement on a company website (which, indeed, the authors used to preview these developments), but it fails to meet the scientific community’s standards of being usable, scalable, and transparent.”

DeepMind responded by increasing the daily quota to 20 generations and promising that it would release the model weights within six months “for academic use.” When it did release the weights, it added significant restrictions. Access is strictly non-commercial and at “Google DeepMind’s sole discretion.” Moreover, scientists would not be able to fine-tune or distill the model.

This prompted an immediate demand for open replications of AlphaFold 3. Within months, companies like ByteDance and Chai Discovery had released models following the training details in the AlphaFold 3 paper. An MIT lab released the Boltz-1 model under an open license in November 2024.

In June 2024, AlQuraishi told the publication GEN Biotechnology that his research group was already working on replicating AlphaFold 3. But replicating AlphaFold 3 posed new challenges compared to AlphaFold 2.

Reverse engineering AlphaFold 3 requires succeeding on a larger variety of tasks than AlphaFold 2. “These different modalities are often in contention,” AlQuraishi told me. Even if a model matched AlphaFold 3’s performance in one domain, it might falter in another. “Optimizing the right trade-offs between all these modalities is quite challenging.”

This makes the resulting model more “finicky” to train, AlQuraishi said. AlphaFold 2 was such a “marvel of engineering” that OpenFold was largely able to replicate it with its first training run. Training OpenFold 31 has required a bit more “nursing,” AlQuraishi told me.

There’s 100 times more data to generate too. Google DeepMind used tens of millions of the highest-confidence predictions from AlphaFold 2 to augment the training set for AlphaFold 3, as well as many more MSAs than it used for AlphaFold 2. OpenFold has had to replicate both. One PhD student currently working on OpenFold 3, Lukas Jarosch, told me that the synthetic database in progress for OpenFold 3 might be the biggest ever computed by an academic lab.

All of this ends up requiring a lot of compute. Mallory Tollefson, OpenFold’s business development manager, told me in December that the project has probably used “approximately $17 million of compute” donated from a wide variety of sources. A lot of that is for dataset creation: AlQuraishi estimated that it has cost around $15 million to make.

OpenFold has an unusual structure

Coordinating all of this computation takes a lot of work. “There’s definitely a lot of strings that Mohammed [AlQuraishi] needs to pull to keep such a big project running in practice,” Jarosch said.

This is where OpenFold’s structure — and membership in the Open Molecular Software Foundation — are essential aspects of the project. I think it also shows a clever alignment of incentives.

Other groups have been quicker to release partial replications of AlphaFold 3: for instance, the company Chai Discovery released Chai-1 in September 2024, while OpenFold 3-preview was only released in October 2025. And scientists needing an open version currently use other models: several people I spoke to praised Boltz-2, released in June 2025. But those replications are either made or managed by companies: Boltz recently incorporated as a public benefit corporation.

Companies can move quickly and marshal resources, but also have incentives to close down access to their models, so that they can license the product to pharmaceutical companies.2

While individual academics have less access to resources, they still have incentives not to share commercially lucrative results. For some areas like measuring how proteins bind with potential drugs, “people have never really made the code available because they’ve always had this idea that they can make money with it,” according to Wilke, the UT Austin professor. He said it’s held back that area “for decades.”

Yet OpenFold, in Jarosch’s estimation, “is very committed to long-term open source and not branching out into anything commercial.” How have they set this up? Partly by relying on pharmaceutical companies for funding.

At first glance, pharmaceutical companies might seem like an odd catalyst for open source. They are famously protective of intellectual property such as the hundreds of thousands of additional protein structures their scientists have experimentally determined. But pharmaceutical companies need AI tools they can’t easily build themselves.

$17 million is a lot of money to spend on compute. But when split 37 ways, it’s cheaper than licensing a model from a commercial supplier like Alphabet’s Isomorphic. Add in early access to models and the ability to vote on research priorities and OpenFold becomes an attractive project to fund.

If the pharmaceutical companies could get away with it, they’d probably want exclusive access to OpenFold’s model. (An OpenFold member, Apheris, is working on building a federated fine-tune of OpenFold 3 exclusive to the pharmaceutical companies who provide the proprietary data for training). But having a completely open model is a good compromise with the academics actually building the model.

From an academic perspective, this partnership is attractive too. Resources from pharmaceutical companies make it easier to run large projects like OpenFold. The computational resources they donate are more convenient for large training runs because jobs aren’t limited to a day or a week as with national labs, according to Jennifer Wei, a full-time software engineer at OpenFold. And the monetary contributions, combined with the open-source mission, help attract engineering talent like Wei — an ex-Googler — to produce high-quality code.

Pharmaceutical input makes the work more likely to be practically relevant, too. Lukas Jarosch, the PhD student, said he appreciated the input from industry. “I’m interested in making co-folding models have a big impact on actual drug discovery,” he told me.

The companies also give helpful feedback. “It’s hard to create benchmarks that really mimic real-world settings,” Jarosch said. Pharmaceutical companies have proprietary datasets which let them measure model performance in practice, but they rarely share these results publicly. OpenFold’s connections with pharmaceutical companies give a natural channel for high-quality feedback.

When I asked AlQuraishi why he had stayed in academia rather than getting funding for a start-up, he told me two things. First, he wanted to “actually be able to go after basic questions,” even if they didn’t make money right away. He’s interested in eventually being able to simulate an entire working cell completely on a computer. How would he be able to get venture funding for that if it might take decades to pan out?

But second, the experience of watching LLMs become increasingly restricted underlined the importance of open source. “It’s not something that I thought I cared about all that much,” he told me. “I’ve become a bit more of a true open source advocate.”

There was no OpenFold 2. OpenFold named its second model OpenFold 3 to align with the version of AlphaFold it sought to replicate. It turns out that confusing model naming is not unique to LLMs.

Boltz claims it will keep its models open source and focus on end-to-end services around its model, like fine-tuning on a company’s custom data. This may remain the case, but Boltz’s incentives ultimately point towards getting as much money from companies as possible.