Waymo and Tesla’s self-driving systems are more similar than people think

Everyone is moving toward transformer-based, end-to-end architectures.

The transformer architecture underlying large language models is remarkably versatile. Researchers have found many use cases beyond language, from understanding images to predicting the structure of proteins to controlling robot arms.

The self-driving industry has jumped on the bandwagon too. Last year, for example, the autonomous vehicle startup Wayve raised $1 billion. In a press release announcing the round, Wayve said it was “building foundation models for autonomy.”

“When we started the company in 2017, the opening pitch in our seed deck was all about the classical robotics approach,” Wayve CEO Alex Kendall said in a November interview. That approach was to “break down the autonomy problem into a bunch of different components and largely hand-engineer them.”

Wayve took a different approach, training a single transformer-based foundation model to handle the entire driving task. Wayve argues that its network can more easily adapt to new cities and driving conditions.

Tesla has been moving in the same direction.

“We used to work on an explicit, modular approach because it was so much easier to debug,” said Tesla AI chief Ashok Elluswamy at a recent conference. “But what we found out was that codifying human values was really difficult.”

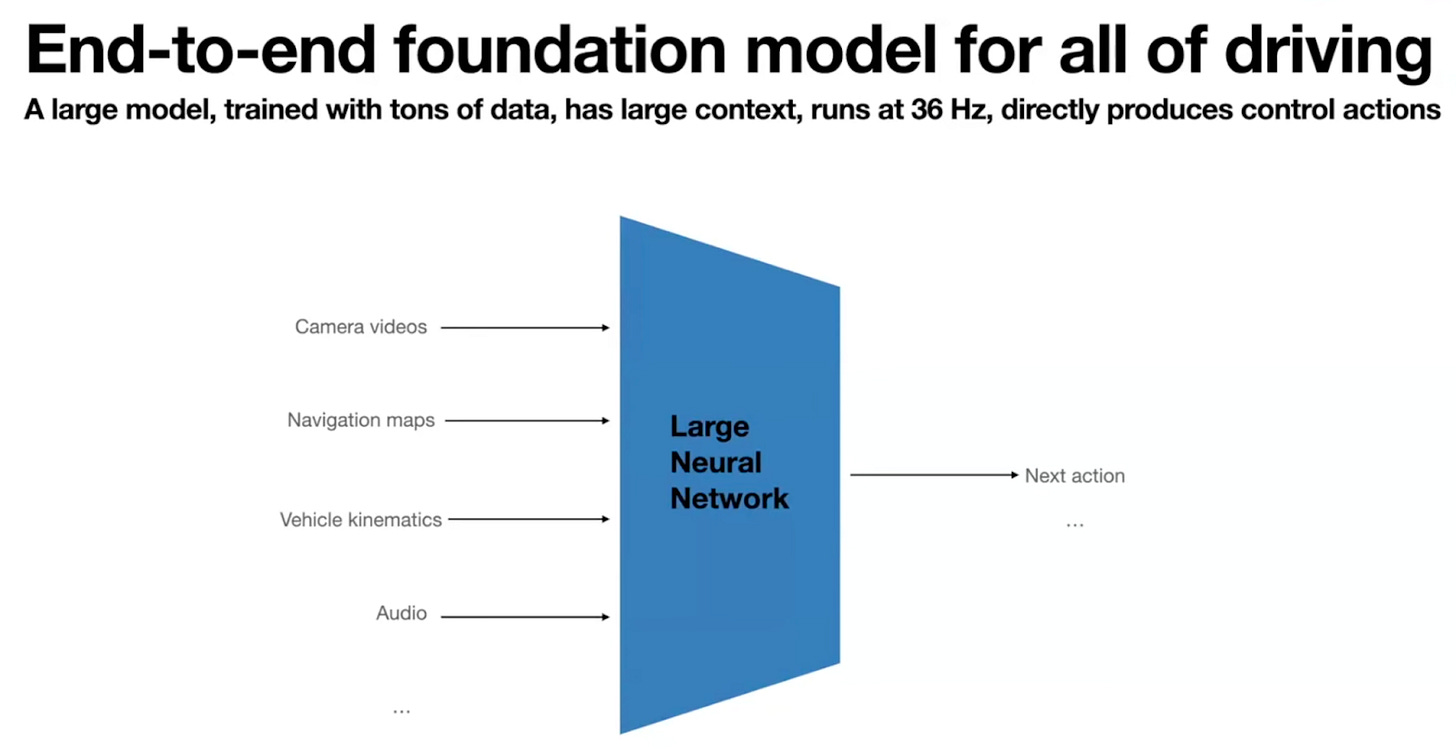

So a couple of years ago, Tesla scrapped its old code in favor of an end-to-end architecture. Here’s a slide from Elluswamy’s October presentation:

Conventional wisdom holds that Waymo has a dramatically different approach. Many people — especially Tesla fans — believe that Tesla’s self-driving technology is based on cutting-edge, end-to-end AI models, while Waymo still relies on a clunky collection of handwritten rules.

But that’s not true — or at least it greatly exaggerates the differences.

Last year, Waymo published a paper on EMMA, a self-driving foundation model built on top of Google’s Gemini.

“EMMA directly maps raw camera sensor data into various driving-specific outputs, including planner trajectories, perception objects, and road graph elements,” the researchers wrote.

Although the EMMA model was impressive in some ways, the Waymo team noted that it “faces challenges for real-world deployment,” including poor spatial reasoning ability and high computational costs. In other words, the EMMA paper described a research prototype — not an architecture that was ready for commercial use.

But Waymo kept refining this approach. In a blog post last week, Waymo pulled back the curtain on the self-driving technology in its commercial fleet. It revealed that Waymo vehicles today are controlled by a foundation model that’s trained in an end-to-end fashion — just like Tesla and Wayve vehicles.

For this story, I read several Waymo research papers and watched presentations by (and interviews with) executives at Waymo, Wayve, and Tesla. I also had a chance to talk to Waymo co-CEO Dmitri Dolgov. Read on for an in-depth explanation of how Waymo’s technology works, and why it’s more similar to rivals’ technology than many people think.

Thinking fast and slow

Some driving scenarios require complex, holistic reasoning. For example, suppose a police officer is directing traffic around a crashed vehicle. Navigating this scene not only requires interpreting the officer’s hand signals, it also requires reasoning about the goals and likely actions of other vehicles as they navigate a chaotic situation. The EMMA paper showed that LLM-based models can handle these complex situations much better than a traditional modular approach.

But foundation models like EMMA also have real downsides. One is latency. In some driving scenarios, a fraction of a second can make the difference between life and death. The token-by-token reasoning style of models like Gemini can mean long and unpredictable response times.

Traditional foundation models are also not very good at geometric reasoning. They can’t always judge the exact locations of objects in an image. They might also overlook objects or hallucinate ones that aren’t there.

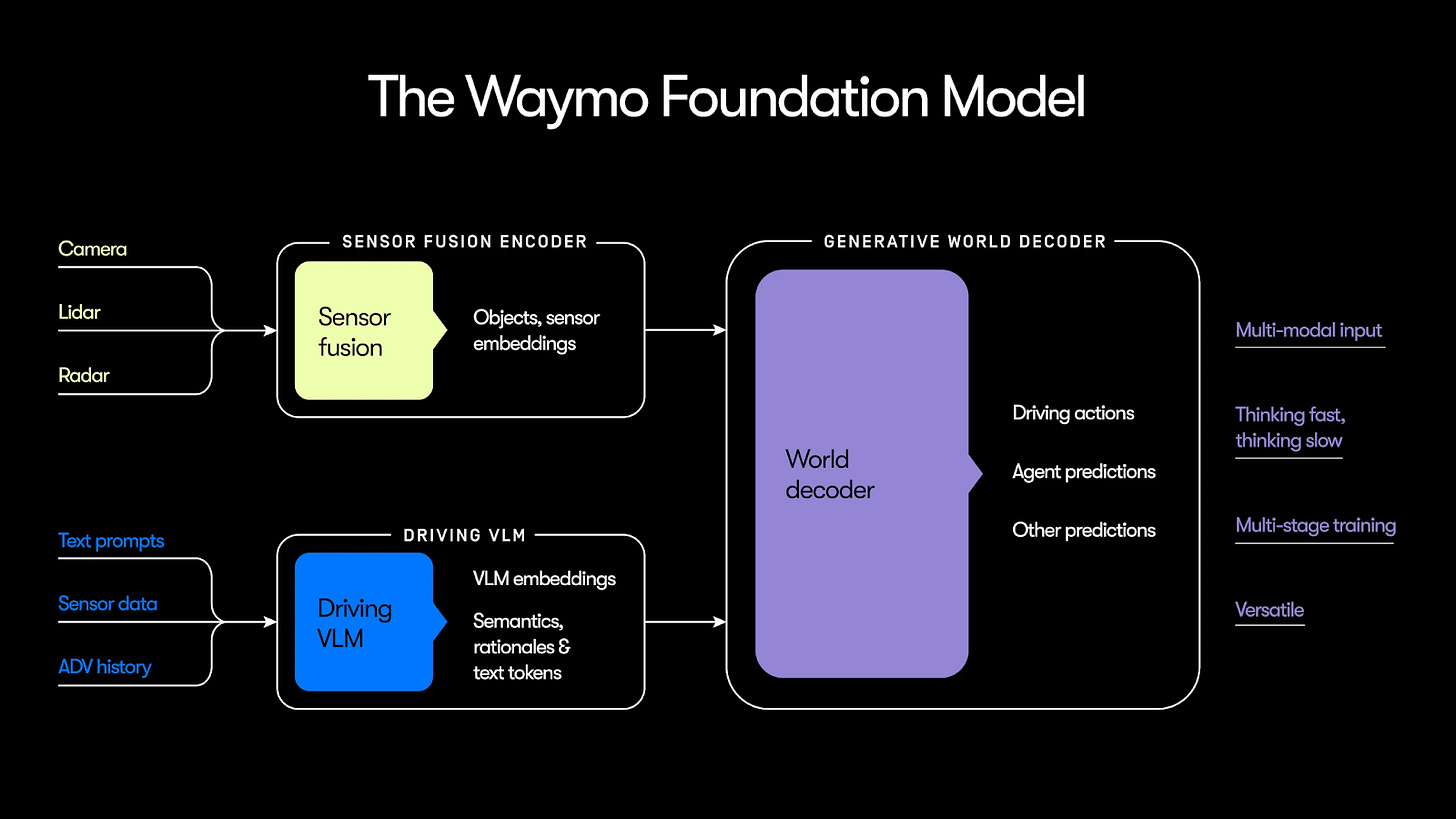

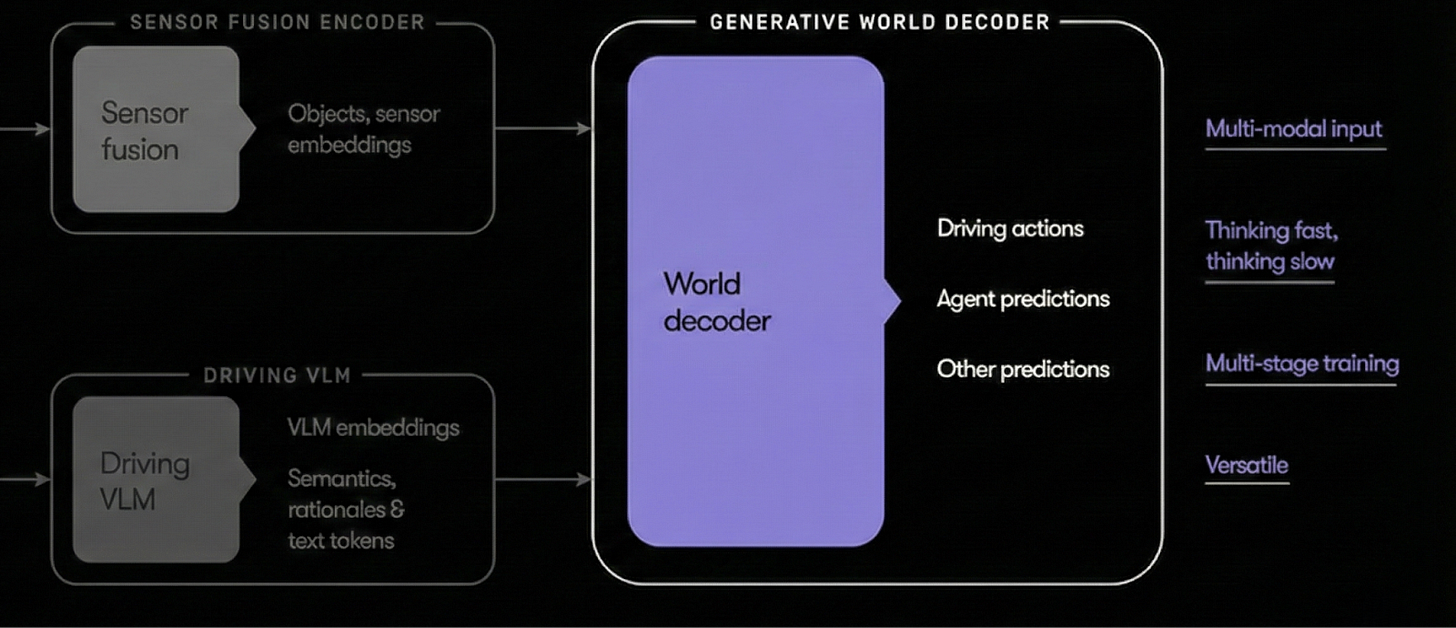

So rather than relying entirely on an EMMA-style vision-language model (VLM), Waymo placed two neural networks side by side. Here’s a diagram from Waymo’s blog post:

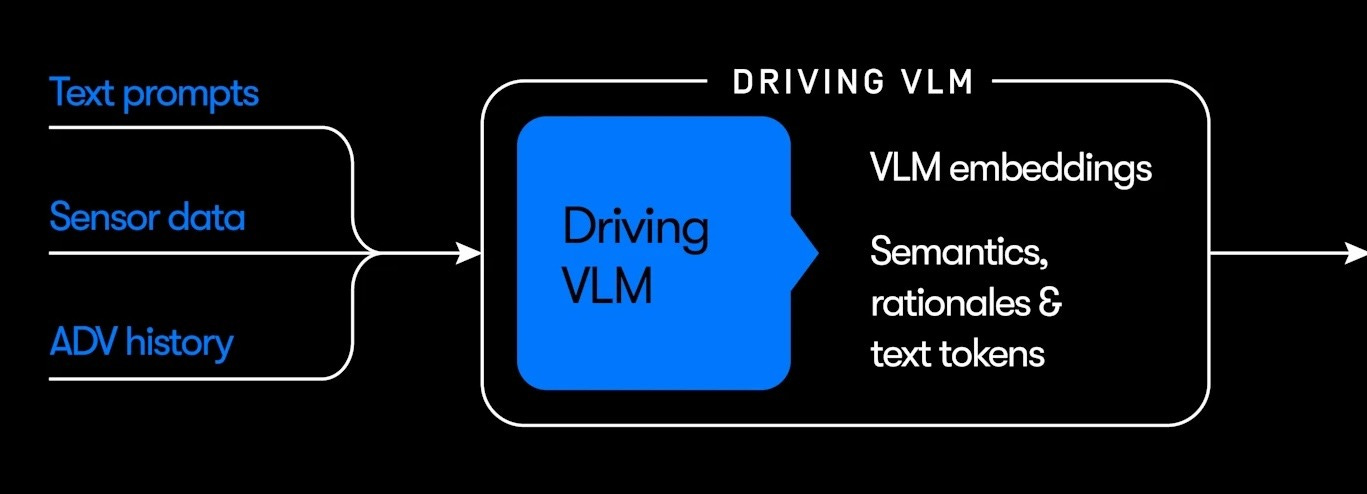

Let’s start by zooming in on the lower-left of the diagram:

VLM here stands for vision-language model — specifically Gemini, the Google AI model that can handle images as well as text. Waymo says this portion of its system was “trained using Gemini” and “leverages Gemini’s extensive world knowledge to better understand rare, novel, and complex semantic scenarios on the road.”

Compare that to EMMA, which Waymo described as maximizing the “utility of world knowledge” from “pre-trained large language models” like Gemini. The two approaches are very similar — and both are similar to the way Tesla and Wayve describe their self-driving systems.

“Milliseconds really matter”

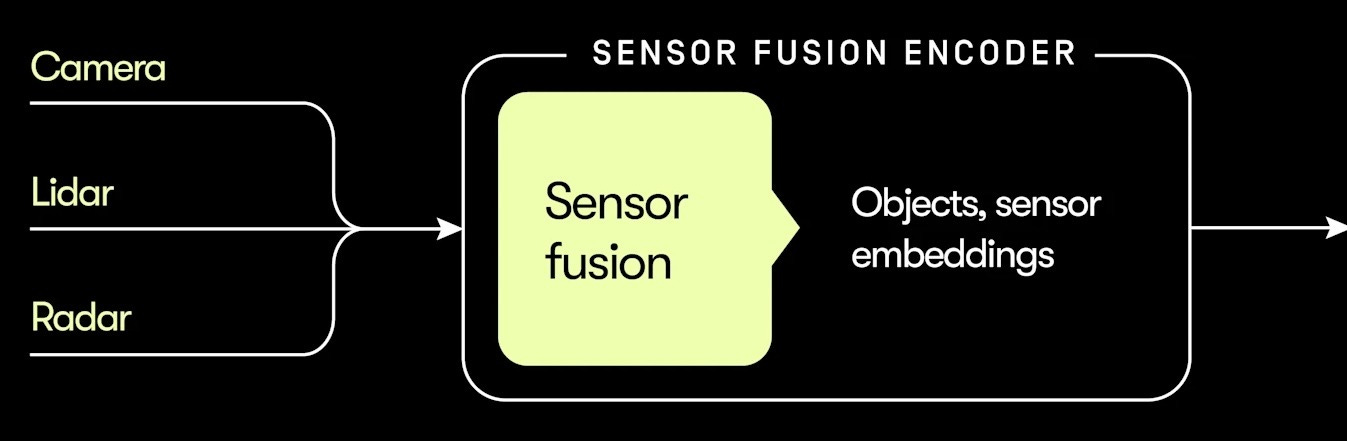

But the model in today’s Waymo vehicles isn’t just an EMMA-like vision-language model — it’s a hybrid system that also includes a module called a sensor fusion encoder that is depicted in the upper-left corner of Waymo’s diagram:

This module is tuned for speed and accuracy.

“Imagine a latency-critical safety scenario where maybe an object appears from behind a parked car,” Waymo co-CEO Dmitri Dolgov told me. “Milliseconds really matter. Accuracy matters.”

Whereas the VLM (the blue box) considers the scene as a whole, the sensor fusion module (the yellow box) breaks the scene into dozens of individual objects: other vehicles, pedestrians, fire hydrants, traffic cones, the road surface, and so forth.

It helps that every Waymo vehicle has lidar sensors that measure the distance to nearby objects by bouncing lasers off of them. Waymo’s software matches these lidar measurements to the corresponding pixels in camera images — a process called sensor fusion. This allows the system to precisely locate each object in three-dimensional space.

In early self-driving systems, a human programmer would decide how to represent each object. For example, the data structure for a vehicle might record the type of vehicle, how fast it’s moving, and whether it has a turn signal on.

But a hand-coded system like this is unlikely to be optimal. It will save some information that isn’t very useful while discarding other information that might be crucial.

“The task of driving is not one where you can just enumerate a set of variables that are sufficient to be a good driver,” Dolgov told me. “There’s a lot of richness that is very hard to engineer.”

So instead, Waymo’s model learns the best way to represent each object through a data-driven training process. Waymo didn’t give me a ton of information about how this works, but I suspect it’s similar to the technique described in the 2024 Waymo paper called “MoST: Multi-modality Scene Tokenization for Motion Prediction.”

The system described in the MoST paper still splits a driving scene up into distinct objects as in older self-driving systems. But it doesn’t capture a set of attributes chosen by a human programmer. Rather, it computes an “object vector” that captures information that’s most relevant for driving — and the format of this vector is learned during the training process.

“Some dimensions of the vector will likely indicate whether it’s a fire truck, a stop sign, a tree trunk, or something else,” I wrote in an article last year. “Other dimensions will represent subtler attributes of objects. If the object is a pedestrian, for example, the vector might encode information about the position of the pedestrian’s head, arms, and legs.”

There’s an analogy here to LLMs. An LLM represents each token with a “token vector” that captures the information that’s most relevant to predicting the next token. In a similar way, the MoST system learns to capture the information about objects that are most relevant for driving.

I suspect that when Waymo says its sensor fusion module outputs “objects, sensor embeddings” in the diagram above, this is a reference to a MoST-like system.

How does the system know which information to include in these object vectors? Through end-to-end training of course!

This is the third and final module of Waymo’s self-driving system, called the world decoder.

It takes inputs from both the sensor fusion encoder (the fast-thinking module that breaks the scene into individual objects) and the driving VLM (the slow-thinking module that tries to understand the scene as a whole). Based on information supplied by these modules, the world decoder tries to decide the best action for a vehicle to take.

During training, information flows in the opposite direction. The system is trained on data from real-world situations. If the decoder correctly predicts the actions taken in the training example, the network gets positive reinforcement. If it guesses wrong, then it gets negative reinforcement.

These signals are then propagated backward to the other two modules. If the decoder makes a good choice, signals are sent back to the yellow and blue boxes encouraging them to continue doing what they’re doing. If the decoder makes a bad choice, signals are sent back to change what they’re doing.

Based on these signals, the sensor fusion module learns which information is most helpful to include in object vectors — and which information can be safely left out. Again, this is closely analogous to LLMs, which learn the most useful information to include in the vectors that represent each token.

Modular networks can be trained end-to-end

Leaders at all three self-driving companies portray this as a key architectural difference between their self-driving systems. Waymo argues that its hybrid system delivers faster and more accurate results. Wayve and Tesla, in contrast, emphasize the simplicity of their monolithic end-to-end architectures. They believe that their models will ultimately prevail thanks to the Bitter Lesson — the insight that the best results often come from scaling up simple architectures.

In a March interview, podcaster Sam Charrington asked Waymo’s Dragomir Anguelov about the choice to build a hybrid system.

“We’re on the practical side,” Anguelov said. “We will take the thing that works best.”

Anguelov pointed out that the phrase “end-to-end” describes a training strategy, not a model architecture. End-to-end training just means that gradients are propagated all the way through the network. As we’ve seen, Waymo’s network is end-to-end in this sense: during training, error signals propagate backward from the purple box to the yellow and blue boxes.

“You can still have modules and train things end-to-end,” Anguelov said in March. “What we’ve learned over time is that you want a few large components, if possible. It simplifies development.” However, he added, “there is no consensus yet if it should be one component.”

So far, Waymo has found that its modular approach — with three modules rather than just one — is better for commercial deployment.

Waymo co-CEO Dmitri Dolgov told me that a monolithic architecture like EMMA “makes it very easy to get started, but it’s wildly inadequate to go to full autonomy safely and at scale.”

I’ve already mentioned latency and accuracy as two major concerns. Another issue is validation. A self-driving system doesn’t just need to be safe, the company making it needs to be able to prove it’s safe with a high level of confidence. This is hard to do when the system is a black box.

Under Waymo’s hybrid architecture, the company’s engineers know what function each module is supposed to perform, which allows them to be tested and validated independently. For example, if engineers know what objects are in a scene, they can look at the output of the sensor fusion module to make sure it identifies all the objects it’s supposed to.

These architectural differences seem overrated

My suspicion is that the actual differences are smaller than either side wants to admit. It’s not true that Waymo is stuck with an outdated system based on hand-coded rules. The company makes extensive use of modern AI techniques, and its system seems perfectly capable of generalizing to new cities.

Indeed, if Waymo deleted the yellow box from its diagram, the resulting model would be very similar to those at Tesla and Wayve. Waymo supplements this transformer-based model with a sensor fusion module that’s tuned for speed and geometric precision. But if Waymo finds the sensor fusion module isn’t adding much value, it can always remove it. So it’s hard to imagine the module puts Waymo at a major disadvantage.

At the same time, I wonder if Wayve and Tesla are downplaying the modularity of their own systems for marketing purposes. Their pitch to investors is that they’re pioneering a radically different approach than incumbents like Waymo — one that’s inspired by frontier labs like OpenAI and Anthropic. Investors were so impressed by this pitch that they gave Wayve $1 billion last year, and optimism about Tesla’s self-driving project has pushed up the company’s stock price in recent years.

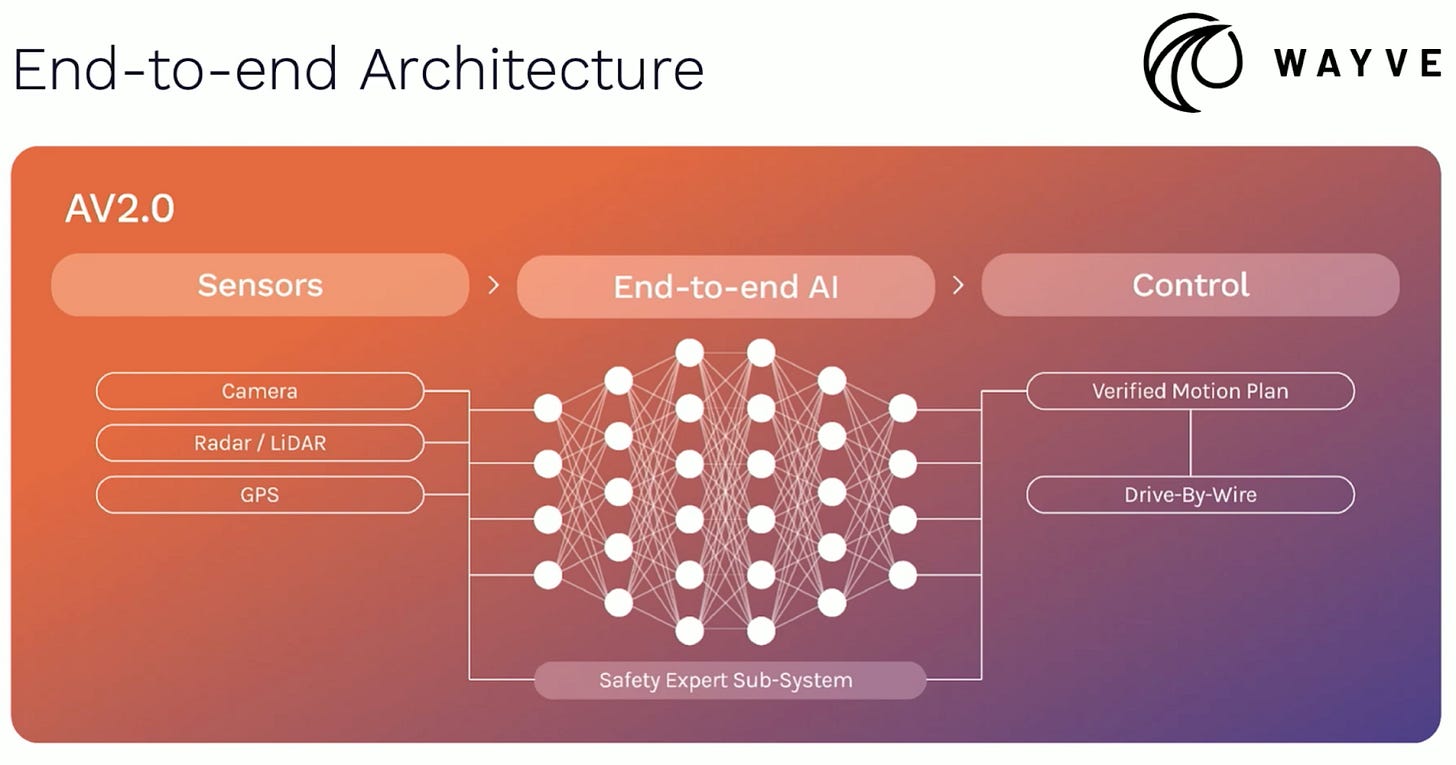

For example, here’s how Wayve depicts its own architecture:

At first glance, this looks like a “pure” end-to-end architecture. But look closer and you’ll notice that Wayve’s model includes a “safety expert sub-system.” What’s that? I haven’t been able to find any details on how this works or what it does. But in a 2024 blog post, Wayve wrote about its effort to train its models to have an “innate safety reflex.”

According to Wayve, the company uses simulation to “optimally enrich our Emergency Reflex subsystem’s latent representations.” Wayve added that “to supercharge our Emergency Reflex, we can incorporate additional sources of information, such as other sensor modalities.”

This sounds at least a little bit like Waymo’s sensor fusion module. I’m not going to claim that the systems are identical or even all that similar. But any self-driving company has to address the same basic problem as Waymo: that large, monolithic language models are slow, error-prone, and difficult to debug. I expect that as it gets ready to commercialize its technology, Wayve will need to supplement the core end-to-end model with additional information sources that are easier to test and validate — if it isn’t doing so already.

The idea that Tesla has any ML work that can be considered cutting edge seems fanciful. Where's the evidence of it? They hardly publish anything. The FSD division is run by a nobody. All observable indicators suggest that Google is on the frontier and Tesla trails.

That is similar to the popular meme that Tesla enjoys a data advantage over Google. Stop and think about that one for a few seconds. "Tesla has more data than Google" is pretty much the craziest claim I've ever heard.

I like how Comma.AI's add-on system layers their smarts atop existing vehicle systems, making use of certified vendor systems to support and validate their own top-level smarts.

For example, Comma (well, actually, the Open Source OpenPilot software) has its own LKAS capabilities that provide LKAS support on vehicles lacking it. However, when a vehicle has its own LKAS, the Comma LKAS capability becomes secondary, providing redundancy.

Comma also uses end-to-end training for their camera-based system, with a separate safety processor ("Panda") validating ("sanity checking") and managing CAN data flowing between Comma and the vehicle. Such safety processors are common throughout many industries, including the electric power grid, nuclear reactors, aircraft avionics, spacecraft and so on.

This is done by Comma despite strictly being a Level 2 system (at least presently). I hope all other self-driving companies are using equivalent safety hardware that exists and runs independently of the host.

This safety module provides a key side benefit: It is the ONLY part of the Comma system that must be validated at the hardware level, allowing the main system hardware to be designed to commercial standards, precisely like a smartphone.