Elon Musk wants to dominate robotaxis—first he needs to catch up to Waymo

I talked to Dmitri Dolgov, co-CEO of Waymo.

This evening, Elon Musk will take the stage in Los Angeles for an event titled “We Robot.” Musk has said that the event, which was originally scheduled for August, will feature a “Tesla Robotaxi unveil.” A lot could be riding on the day’s announcements.

The stock market values Tesla at $755 billion, far more than companies like General Motors ($53 billion) and Ford ($42 billion) that sell more vehicles than Tesla. Tesla’s high valuation seems to reflect hopes that Tesla will dominate the emerging market for driverless cars.

That’s certainly Musk’s view. During a July earnings call, Musk told investors that Tesla will “solve autonomy.”

"If you don't believe it, sell the stock," Musk said.

Yet Tesla’s engineers have struggled to meet the ambitious timelines announced by Musk over the years. Since 2016, Musk has repeatedly claimed that Tesla is less than two years from full autonomy. Yet one independent evaluation of Tesla’s latest Full Self Driving software, version 12.5, found that it required a human intervention once every 13 miles. That’s far short of the level of reliability needed for driverless operation.

In contrast, Google’s Waymo has been offering fully driverless rides since 2020. In August, Waymo reached 100,000 weekly rides, a 10-fold increase over the preceding year. Waymo now offers service in four cities, with further expansion planned in the new year.

Last week I talked to Dmitri Dolgov, co-CEO of Waymo, about how Waymo has gotten where it is today and where it’s going next. An engineer by training, Dolgov has been at Waymo since it began as the Google self-driving car project in 2009.

To position Tesla as the market leader, Musk needs to portray Waymo’s approach as a technological dead end. Over the years, Musk has made a number of claims about Waymo that get endlessly repeated by Tesla fans. So I asked Dolgov about some of these claims.

In reality, Tesla and Waymo’s technology is more similar than Musk or his acolytes like to admit. The main difference is that Waymo started offering driverless rides four years ago, whereas Tesla has yet to offer its first driverless ride.

Claim #1: Waymo’s software is based on hand-coded rules

The last time I wrote an article comparing Waymo and Tesla, reader BobC had the following comment: “[Waymo’s] system appears to rely on lots of hand programming and manual classification, meaning their system likely is fragile and difficult to scale.” This is a viewpoint I hear a lot when I talk to Tesla fans. But it’s wrong—or at least several years out of date.

When Google launched its self-driving car project in 2009, it probably did “rely on lots of hand programming and manual classification” because modern deep learning techniques hadn’t been invented yet.

In 2012, a landmark paper demonstrated that a type of AI model called a convolutional neural network could dramatically improve the accuracy of image classification. That discovery not only kicked off the deep learning revolution, it was directly relevant for self-driving cars, which need to identify and classify objects like vehicles, pedestrians, and stop signs.

Self-driving software is conventionally divided into three stages: perception, prediction, and planning. By the late 2010s, Waymo was using neural networks extensively for perception. But the company was still using older techniques for prediction and planning. Dolgov told me that during this period “we were kind of bumping up against a ceiling” with early deep learning techniques.

Then in 2017, Google researchers invented the transformer architecture that powers today’s large language models. Their colleagues at Waymo soon realized that it could be used for self-driving—including prediction and planning tasks where older machine learning techniques hadn’t worked well.

“We had this insight that this problem of reasoning in the space of trajectories and decision making for autonomous vehicles is not unlike how language works,” Dolgov told me.

The transformer had “some of the nicer properties that we were struggling to achieve with convolutional networks,” Dolgov said. Transformers provided a “big boost across the stack, including perception, generative models for planning and behavior prediction.”

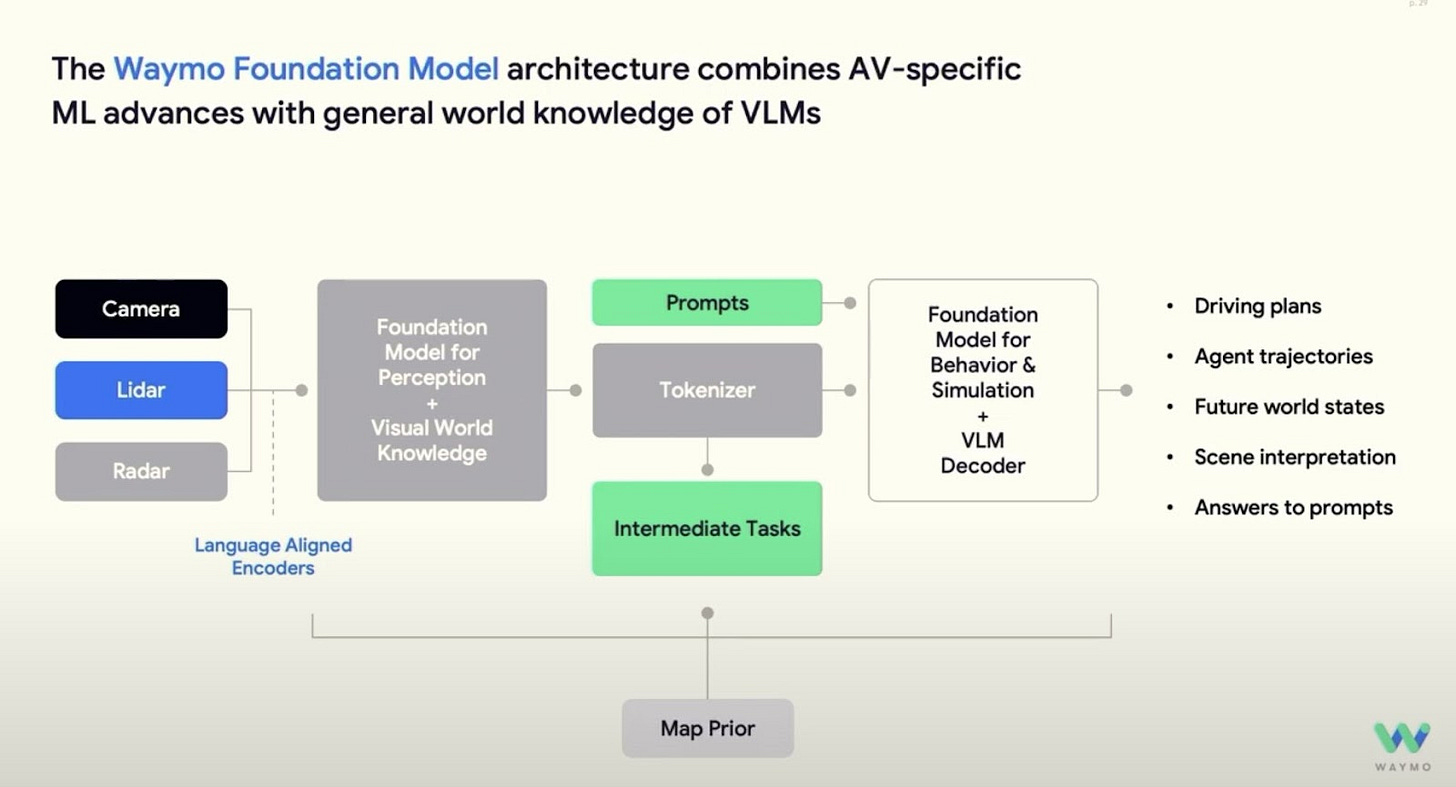

Over the last couple of years, Waymo has published a series of papers on using transformer-based networks for both perception and prediction. At a talk last month, Dolgov showed this diagram of the modern Waymo Driver:

Two things are notable here. First, Waymo is using transformer-based foundation models for all stages of its self-driving pipeline: perception, prediction, and planning. Second, the whole system is trained end to end. During training, gradients from the behavior network propagate backwards to the perception network. Paying readers can read my September article that explains all of this in more detail.

For its part, Tesla began experimenting with deep learning around 2017.

Andrej Karpathy is a computer scientist who led Tesla’s self-driving team from 2017 to 2022. “When I joined, there was no computer vision team,” Karpathy said in a 2022 interview. “Tesla was just going from the transition of using Mobileye, a third party vendor for all of its computer vision, to having to build its computer vision system.”

Karpathy said that in 2017, Tesla had only “two people training neural networks” on a workstation they kept under a desk.

By 2019, Tesla’s self-driving software was using neural networks for perception—but that was it. “Essentially, right now AI and neural nets are used really for object recognition,” Elon Musk said at a 2019 event showing off Tesla’s self-driving technology.

Prediction and planning were still being done using older techniques. At the same 2019 event, Karpathy said that he expected Tesla to add a “fleet learning component”—that is, neural networks trained using real-world data—for prediction and planning. Karpathy predicted that Tesla’s then-current approach, “writing all of those rules by hand,” was “going to quickly plateau.”

FSD version 12, released last year, was the first version to use an end-to-end neural network. In a tweet last year, Musk said that Tesla was getting ready to introduce a new neural network for vehicle control. He said this would “drop >300k lines of C++ code by ~2 orders of magnitude.”

So I see more similarities than differences in the evolution of Waymo and Tesla’s self-driving software. Both companies made little to no use of neural networks in their early systems. Both companies started using neural networks for perception in the late 2010s. And both companies only recently shifted to end-to-end architectures that used neural networks for all stages of the self-driving pipeline.

Claim #2: Waymo is highly dependent on maps

Waymo’s vehicles have highly detailed maps of areas where they operate. Tesla fans portray this as a weakness, claiming it will be astronomically expensive for Waymo to create and update these maps nationwide.

But according to Dolgov, this criticism misunderstands Waymo’s technology.

“The world changes,” Dolgov told me. “You can’t expect to have a perfect map. And of course we don’t. Every day, probably hundreds of times, if not thousands of times, we drive through construction zones where the world has changed very drastically.”

Dolgov said the cost of collecting map data is “not a significant factor in terms of our expansion into places. It is a contributor to the overall cost but there are many other things and it is not at the top of the list.”

Dolgov declined to share numbers, but a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation should make it clear this isn’t a significant issue. For example, there are 43,000 lane-miles of roads in the San Francisco metro area. Let’s suppose—conservatively—that it costs $50 to collect and process one lane-mile of map data (that’s enough money to buy an expensive mapping vehicle, pay someone to drive it on every road several times, and have plenty of money left over for post-processing). Then the total cost of creating a map for the San Francisco metro area would be around $2 million—a trivial sum given the size of the ride-hailing market in San Francisco.

What about updating the map? Once Waymo’s commercial service is up and running, vehicles can collect data automatically as they drive around San Francisco streets. There’s no need for a separate mapping fleet. And a lot of post-processing can be automated. Tesla has tweeted about its “fleet scale auto-labeling” technology to automatically create detailed maps from video footage. I would be shocked if Waymo didn’t have a similar technology.

Meanwhile, Tesla also uses maps. Back in August, I drove a Tesla vehicle on a divided highway. I noticed that the car always knew how many lanes were on the opposite side of the road, even when there was a high wall in the median. The car was clearly getting this information from an onboard map.

So yes, Waymo uses more detailed maps than Tesla, and that will modestly increase the cost of expanding to new cities. But I believe Dolgov when he says this won’t be an obstacle to expanding Waymo’s service. And there’s no reason to think the Waymo Driver is less able than Tesla FSD to cope with a map that’s out of date.

Claim #3: Waymo’s software can’t handle freeway driving

It’s true that Waymo does not yet offer driverless freeway rides to paying customers. But neither does anyone else in the industry. And Waymo has made more progress on freeway driving than any of its rivals, including Tesla.

Back in 2013, the Google self-driving car program built a freeway driving assistant—similar to Tesla’s later Autopilot system—and let Google employees use it on their commutes. The self-driving system worked so well that employees quickly started to over-rely on it. They’d spend their commutes texting or putting on makeup instead of paying attention to the road. The experience convinced Google executives not to sell driver assistance technology to carmakers and focus instead on a fully driverless taxi service.

So why don’t Waymo’s commercial robotaxis use freeways today? Most of the time, freeways are easier to navigate than surface streets. They have wide, well-marked lanes and hardly any pedestrians or bicyclists. But even on freeways, crazy stuff happens once in a while.

“You have mattresses falling off of the car in front of you,” Dolgov told me. “You have cars getting into accidents and spinning out. You see people driving at extreme speeds. You see people falling off of motorcycles. You see people jaywalking. Because of the speeds involved, we want to make sure that we have very high confidence before we open up.”

When a driverless vehicle encounters a problem it can’t handle, it goes into what’s called a minimal risk condition—it slows down and stops. That’s usually easy to do on a city street going 20 mph. It can be much harder to do safely on a freeway going 70 mph. Stopping too suddenly on the freeway can cause a traffic jam or even a pileup.

Despite all of those challenges, Waymo began driverless testing on freeways in Phoenix in January and in San Francisco in August.

“We're going to follow the same playbook and the same process that we have always applied for scaling,” Dolgov told me. I would not be surprised if Waymo began offering freeway rides for paying customers in the coming months.

Tesla hasn’t had to grapple with these challenges yet because it still has a human driver in every vehicle. When Tesla’s FSD software encounters a situation it doesn’t understand, it simply beeps to signal for the human to take over. If and when Tesla goes fully driverless, it will need a more sophisticated approach.

Claim #4: Waymo cars depend on remote assistance

This claim is true. Waymo has a staff of people to provide vehicles with remote assistance when they get “stuck.” And I view this as one of the big unanswered questions about Waymo’s technology.

Waymo has long acknowledged the existence of these remote operators, but it hasn’t provided much detail about where they’re located, what they do, or how often they interact with Waymo’s vehicles. This was one of the few topics Dolgov wouldn’t say much about in our interview last week. Until Waymo provides more details (as competitor Zoox did last month), I think the public has cause to be skeptical.

At the same time, some people think the existence of remote operators means the vehicles aren’t actually self-driving. They suspect Waymo has a secret room full of people with steering wheels that are actually driving Waymo’s vehicles. This isn’t true, according to Dolgov.

“The cars are fully autonomous,” Dolgov told me. “They are responsible for everything that is safety related, and if connectivity goes away they will keep driving.”

I believe him. I also think it’s a mistake to see Tesla’s lack of remote operators as an advantage.

No matter how quickly Tesla’s self-driving technology improves, it will be many years before it’s good enough to handle literally any situation it encounters. This means that for at least a few years, Tesla’s driverless vehicles are going to need occasional assistance from humans. The only question is whether that person will be in the car or remote.

So I’ll be watching tonight to see if Musk mentions plans to hire remote operators. If he doesn’t, that would be a sign that the company is not yet serious about creating a fully driverless service.

Waymo is not a car manufacturer

At this point you might be wondering why Waymo isn’t expanding more quickly. If Waymo has a highly scalable end-to-end architecture and collecting map data isn’t prohibitively expensive, why is Waymo only operating in four cities?

One big reason is that manufacturing Waymo’s cars is a slow and expensive process. Waymo’s current fleet is made up of Jaguar I-Paces that are rumored to cost more than $100,000 each. Waymo may need to bring that cost down to make its service financially viable.

Every Waymo vehicle has lidar sensors that add thousands—perhaps tens of thousands—of dollars to the cost of each vehicle. Another major cost is upfitting, the process of taking an off-the-shelf car (like a Jaguar I-Pace) and modifying it for self-driving. Police departments can spend $50,000 adding the lights, sirens, and other equipment to a police car. I would not be surprised if Waymo’s process for upfitting the Jaguar I-Pace is similarly expensive.

One reason these vehicles are expensive is that Waymo has only deployed a few hundred of them. Manufacturing costs tend to fall when a product is produced at scale. The key is for an automaker to add Waymo’s hardware to vehicles while they’re still on the assembly line, avoiding the costly upfitting process.

The problem is that setting up a new assembly line is expensive. So it only makes sense for an automaker to invest in a custom assembly line if they expect Waymo to buy thousands of vehicles.

Until recently, Waymo only had a few hundred vehicles in its entire fleet, so it was forced to buy stock vehicles and modify them itself. But now Waymo is likely getting ready to order thousands—and soon tens of thousands—of vehicles as it expands to new cities. That will inevitably bring down the price Waymo pays for each vehicle. But it will take time for Waymo’s automotive partners to set up new production lines.

In 2021, Waymo announced plans to develop a vehicle with the Chinese carmaker Zeekr that is being tested on public roads today. Dolgov told me that making the manufacturing process simpler and less expensive was Waymo’s “primary focus” with the Zeekr vehicle.

However, the Biden Administration recently slapped a 100 percent tariff on Chinese vehicles, which could double the price Waymo pays for Zeekr-based vehicles. Continued geopolitical tensions could put further pressure on Waymo not to build a driverless service using Chinese vehicles.

Last week, Waymo announced a deal with Hyundai to customize its Ioniq 5 electric vehicle for Waymo’s use. But on-road testing for this vehicle isn’t scheduled to begin until late next year, with mass production likely to follow a year or two after that.

At the same time, Jaguar recently announced it was halting production of the I-Pace at the end of 2024. Waymo appears to be stockpiling I-Paces, but it’s not clear how many Jaguar vehicles Waymo has or how quickly Waymo can add them to its commercial fleet.

So Waymo may face a vehicle shortage over the next year or two.

This creates a window of opportunity for Tesla. If Tesla can get its self-driving technology working in the year or so, then it may be able to reach a significant scale before Waymo can.

“People think that Waymo is ahead of Tesla. I think personally Tesla is ahead of Waymo,” Karpathy said in a September interview. “I know it doesn’t look like that but I’m still very bullish on Tesla and its self-driving program. Tesla has a software problem. Waymo has a hardware problem. And I think that software problems are much easier.”

What he means is that Tesla already has a fleet of millions of vehicles that could be able to run Tesla’s self-driving software once it is good enough for safe driverless operation. In contrast, Waymo is trying to build a fleet from scratch, and that’s going to be a slow and difficult process.

It won’t be easy for Tesla to scale a robotaxi service

If vehicle manufacturing were Waymo’s only bottleneck, I’d find this argument pretty persuasive. But I think Karpathy is ignoring other bottlenecks that will apply to Tesla as much as Waymo.

Take maintenance, for example. No matter how good Waymo or Tesla’s software is, their cars are still going to get flat tires sometimes. If Tesla is running a fully driverless taxi service, customers are going to expect Tesla to send someone out to replace the tire and get the vehicle on its way.

Waymo is currently building out a network of depots in Los Angeles, Phoenix, and San Francisco and hiring people to clean, charge, and repair its cars. Recently Waymo signed a deal to offload some of these functions to Uber in its next two markets: Austin and Atlanta. But it will still take time for Uber to build the infrastructure required to provide these services.

If Tesla is serious about entering the robotaxi market, it’s going to need the same kind of infrastructure. Tesla may be able to hire third-party companies to do much of this work, but it’s still going to take a lot of time to identify partners and negotiate deals across dozens of cities.

So it’s not like Tesla is going to be able to create a robotaxi network simply by pushing out a better version of FSD. Tesla is going to have to do a lot of the same hard work as Waymo.

So that’s a big thing I’ll be watching for at tonight’s event: is Tesla building the non-software infrastructure that will be required to offer a nationwide taxi network? If not, then I’m going to be very skeptical of any claims about an imminent Tesla robotaxi service, no matter how impressive Tesla’s demos are.

This made me chuckle: "Tesla has a software problem. Waymo has a hardware problem. And I think that software problems are much easier"

AI software is the great intellectual challenge of the 21st century. Building cars at scale was perfected by Henry Ford in 1910. Cars have been a commodity for the 100+ years since.

In Karpathy's defense, as your article explains, building a lot of cars can take a few years, and perhaps that will partly offset Waymo's many-year lead on software. But what he says is still a chuckle

Indeed, Tesla does not have any magic way of leap-frogging Waymo. Same hard problems everywhere.

Besides, Tesla does not use lidar. Vision alone was repeatedly shown to be not robust enough.

That said, Waymo still likely has work cut for it. Freeway driving, rare events. It is not only a matter of having more cars. But unlike Musk, Dolgov does not think bluster will pave over issues.