Seven big advantages human workers have over AI

Geoffrey Hinton says "there's nothing special about people." He's wrong.

Computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton spent half a century doing foundational research that made today’s AI models possible. But since leaving Google last year, Hinton has shifted his focus to the economic and policy implications of AI. He has done numerous media interviews warning that powerful AI posed a risk to the jobs and very survival of human beings.

“There’s nothing special about people,” Hinton said in an interview last month with Bloomberg’s Wall Street Week. “We're incredibly complicated. And we're very wonderful to other people. But there's nothing you can't replicate in other material.”

Hinton believes that it’s only a matter of time before AI systems begin to outperform humans at a wide range of jobs. He worries that this will produce mass unemployment and a dramatic increase in inequality.

I agree with Hinton on one level—I don’t think there’s any specific cognitive task that an AI model won’t be able to do eventually. But this doesn’t imply that “there’s nothing special about people.” Some of the things that make us special—and valuable in the marketplace—are more related to what we are than what we can do.

People don’t just value other people for their ability to carry out specific tasks; they value characteristics that make us human—including our uniqueness, vulnerability, independence, and connections to other human beings. Artificial systems are unlikely to gain these characteristics no matter how rapidly machine learning and robotics progress. And this means that many jobs—including some of the most lucrative and prestigious ones—are going to stay in human hands for the foreseeable future.

1. Humans have physical bodies

“In the industrial revolution, we made human strength irrelevant,” Hinton said. “Now we're making human intelligence irrelevant. And that's very scary.”

I suspect this would be news to the two delivery men who wrestled a refrigerator up a flight of steps and into my kitchen a few weeks ago. Their jobs absolutely required human strength, and I don’t think there’s a robot in the world that could do it.

And the same is true for many other jobs. In fact, there are tens of millions of jobs in the United States that involve manipulating objects in the physical world:

Food preparation and serving (13.2 million workers)

Production operations (8.8 million)

Construction and extraction (6.2 million)

Installation, maintenance, and repair (6 million)

Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance (4.4 million)

Farming, fishing, and forestry (0.4 million)

In total, these occupations employ about 39 million people. Then there are another 45 million jobs providing services to patients, students, clients, or the general public:

Sales (13.4 million)

Education and libraries (8.7 million)

Protective services (3.5 million)

Personal care and service (3 million)

Community and social services (2.4 million)

It’s technically possible for many—maybe most—of these jobs to be done over a Zoom call. But almost all of them can be done more effectively face-to-face. A tutoring chatbot might be a useful supplement to a human second grade teacher, for example, but it’s hard to imagine elementary schools replacing teachers with chatbots any time soon.

So that’s a total of 84 million jobs—about half of all jobs in the US—that can’t be done effectively over Zoom. And this means that they also can’t be done by an AI model running in a data center. Could robots change that?

I’ve broken the occupations above into two groups because I think the analysis is different for each group. Let’s focus first on jobs that involve manipulating tangible objects.

2. Humans are flexible and self-repairing

In July, podcaster Nathan Labenz interviewed Rajat Bhageria, founder and CEO of Chef Robotics. Chef sells a robotic arm that scoops food into a plate or bowl. According to Bhageria, “food assembly” tasks like this account for 70 percent of the labor in the meal preparation industry. You can see one of their robots in action here:

A simple robot like this could dramatically improve the productivity of food preparation facilities, but it won’t eliminate human workers from food preparation. For example, when these scooping robots run out of ingredients, they need a human worker to bring them another bowl. Human beings are also needed to install, maintain, and repair the robots.

In other words, human workers complement special-purpose robots. Installing scooping robots eliminates scooping jobs, but it simultaneously creates new jobs operating and repairing the robots. And those jobs that are likely to be more interesting (and pay better) than the old scooping jobs. This type of automation is a recipe for rising productivity and wages, not mass unemployment.

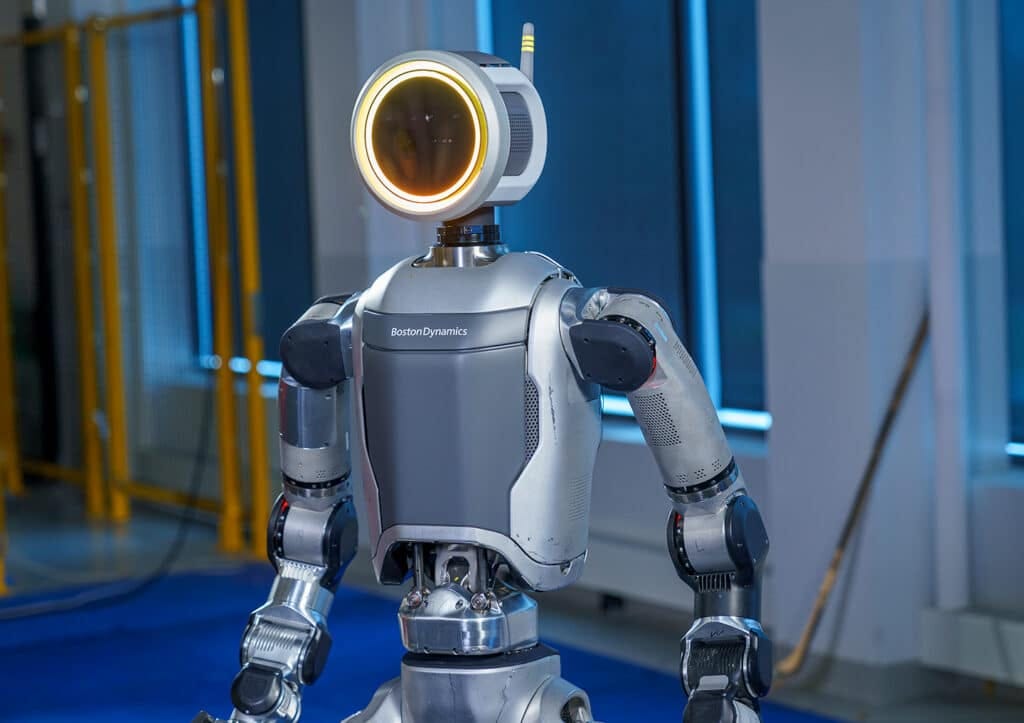

Could this be only a temporary situation? Some companies are working on humanoid robots that could eventually replace all the human workers on a factory floor. However, complex humanoid robots are likely to require far more maintenance than simple robots. So while humanoid robots might be able to replace most workers on a factory floor, they are likely to create even more jobs maintaining and repairing the robots. Indeed, these costs might be so high that it doesn’t make financial sense to use humanoid robots in many cases.

So humans are special because our bodies are simultaneously very versatile and very durable. Maybe we’ll invent robots like that eventually, but I don’t expect it to happen any time soon.

3. Humans like to interact with other humans

Now let’s consider my second broad category of in-person jobs: jobs like nursing, teaching, and sales that mainly involve interacting with other people. Some of these jobs can be done via video calls. And we can probably invent robots to perform other aspects of these jobs. But in either case, the experience of the patient, student, or customer just isn’t going to be the same.

The clearest example of this is nannies. Even if a humanoid robot can change diapers and give babies bottles of milk, most parents are going to prefer a flesh-and-blood nanny because babies want and need interactions with other human beings.

The same is true, to at least some extent, for elder care workers, elementary school teachers, therapists, nurses, lobbyists, waiters, and so forth. To be clear, not everyone is going to want the human-provided version of these jobs. Some people prefer a chatbot therapist—or might not think a human therapist is worth the higher cost.

But enough people are going to prefer human-provided services to create robust demand for human workers even after robots have mastered the mechanical aspects of these jobs.

4. Humans care what other humans think

Last year I wrote about my first session with a personal trainer:

On one level my trainer’s job is to design a workout for me and give me feedback on my technique. But if I just wanted fitness information, I could get it a lot cheaper from books, YouTube videos, or a workout app. On a deeper level my trainer’s job is motivational: to design a workout for me and then be disappointed in me if I don’t show up and do the work.

Many jobs try to influence people’s behavior by taking advantage of the fact that people care what other people think.

Take convenience stores, for example. Typically someone sits behind a register and rings up customer orders. Self-checkout technology has gotten good enough that it would be fairly easy to eliminate this job. Yet as far as I know nobody does this. One likely reason: a totally empty store would have a huge shoplifting problem.

This isn’t just because store clerks can physically prevent people from shoplifting—many stores actually discourage their clerks from confronting shoplifters. But the presence of store employees still deters shoplifting because most people have a sense of shame that prevents them from committing a crime in plain view of another person. A restocking robot wouldn’t have the same salutary impact on customer behavior.

There are lots of other examples like this in both positive and negative directions.

Teachers, coaches, therapists, and executive assistants all play a role similar to personal trainers: a big part of their job is to give people positive feedback when they do a good job, and that feedback means more coming from another human being.

Security guards, police officers, and lifeguards all have jobs like retail clerks: part of their job is to give people negative feedback when they misbehave, and that feedback means more coming from another human being.

Most of these jobs include some tasks that can be automated. For example, there are touchscreen kiosks that check people’s IDs. But placing such a kiosk at the entrance of a building would not encourage people to be on their best behavior the way a human security guard can.

By the same token, I expect teaching chatbots will help students with homework questions. But a flesh-and-blood teacher will be much better at motivating students to do their homework.

5. Humans are scarce

A 2012 story in the Wall Street Journal said that “Starbucks baristas are being told to stop making multiple drinks at the same time” after “customer complaints that the Seattle-based coffee chain has reduced the fine art of coffee making to a mechanized process with all the romance of an assembly line.”

Customers weren’t complaining about the quality of the coffee. Rather, having another human being give their coffee undivided attention for a minute or two gave their visit to Starbucks a sense of luxury.

Luxury products are defined by their scarcity. One thing that’s reliably scarce—and gets more scarce as society gets richer—is the time and attention of other people.

So it’s not a coincidence that the fanciest restaurants tend to be the most labor-intensive. In the front of the house are people to hang up jackets, refill water glasses, and sweep crumbs off the table. In the back, people carefully arrange every dish so that it looks like a work of art.

I expect this effect to get more powerful as more routine tasks get automated. Maybe in a decade we’ll have robots that can fill water glasses, hang up jackets, and arrange elaborate dishes on plates. But once the novelty wears off, I expect high-end restaurants to continue making heavy use of human labor to distinguish themselves from less exclusive rivals.

You see the same phenomenon in the corporate world. One reason companies assign salespeople to important customers is to signal that they value the relationship. More important customers get access to the vice president for sales, and the most important customers get direct access to the CEO.

Even if AI systems become capable of performing all the tasks of today’s salespeople, that does not imply that the job of salesperson will become obsolete. If anything, hiring human salespeople will become even more valuable as a way for a company to distinguish itself from competitors.

6. Humans are independent

Last year I asked a friend who works as a public defender whether she thought an AI system would be able to do her job. I was expecting her to talk about how an AI lawyer wouldn’t be able to represent clients in the courtroom. But she took the conversation in an unexpected direction.

She said that a big part of her job was just getting clients to trust her. A defense lawyer can’t do her job effectively unless her client trusts her enough to share the details of the case. Yet many criminal defendants do not trust “the system” and are reluctant to talk to anyone.

Now imagine if the same defendant were given a chatbot, rather than a human being, as a lawyer. The inability to have a face-to-face conversation would obviously make it harder to build a rapport. The defendant might also have entirely legitimate questions about the chatbot. Who programmed it? Does it have a hidden agenda? Who has access to the chat logs? Will the defendant be talking to “the same” chatbot from one conversation to the next?

An attorney is expected to exercise independent judgment on behalf of her client. She is supposed to protect the client’s confidentiality. And she’s supposed to do these things even if they run contrary to the interests of the people who pay her salary.

It is hard to give an AI system this kind of independence, and even harder to convince users that they have it. Every AI system runs on a server that’s owned and operated by somebody. That person or company will always have the ability to modify the model and may also be able to view its past conversations. So someone who chooses a chatbot for a lawyer is effectively trusting a company—which means trusting an unknown number of people who work for that company.

This problem isn’t limited to lawyers. Some people think that in the future, many companies will choose AI models, rather than human beings, to serve as their CEOs. An important characteristic of a CEO is independence: a CEO is supposed to put the interests of the company first.

But if a company made a chatbot its CEO, it would effectively be putting the maker of that chatbot in charge of the company. The AI vendor would have the power to change the behavior of the CEO and perhaps even to view the CEO’s private conversations.

Maybe the AI vendor would promise not to mess with the AI CEO without the approval of the board. But the very fact that it’s possible to modify the software or view its chat histories is going to influence the way other people interact with an AI CEO.

For example, a CEO needs to be able to make credible promises to employees, customers, suppliers, investors, and so forth. And part of what makes a CEO’s promises credible is the fact that she can resign in protest if her board tries to make her break her promises or do something unethical. Because such a resignation would be embarrassing and inconvenient, boards tend to give CEOs a certain amount of autonomy.

An AI CEO would have much less leverage. A corporate board wouldn’t need to fire an uncooperative AI CEO, it could simply modify its programming. This means that an AI CEO would have less credibility any time it tried to make commitments on behalf of the company—and hence would be less effective at the job than a human CEO.

7. Humans form relationships with other humans

Part of the value any senior executive brings to a new job is their professional network. Often a new CEO will try to hire people she worked with earlier in her career. And this is a case where independence really matters.

If a former boss tries to recruit you to work at his new company, you are more likely to say yes if you had a good experience at the previous job. But this only works because human managers have stable identities that persist from one job to the next.

The same point applies to other important roles in the economy. Success as a venture capitalist depends on developing relationships with startup founders. Conversely, success as an entrepreneur depends on developing relationships with investors.

A key part of journalism is developing trusted relationships with sources. And sources almost always develop personal relationships with specific reporters. If a reporter switches to a new job, they’re usually able to take their source relationships with them.

Indeed, I’d say that cultivating relationships like this is important in almost every elite profession—politics, law, finance, technology, and so forth. Making partner at a law firm usually requires developing strong relationships with the firm’s senior partners and major clients. Success as a lobbyist requires developing strong relationships with clients and policymakers.

I’m not going to claim that AI systems will never be able to develop relationships with people. But I do think they are going to be at a big disadvantage, relative to humans, in the high-stakes networking game. And some sources of human advantage are going to persist no matter how capable AI systems get.

Strong human relationships are almost always developed through face-to-face interactions. AI systems can’t meaningfully participate in relationship-building rituals like going out for a drink—and not only because they lack physical bodies.

A human being can only be in one place at a time, so going out for a drink with someone sends a credible signal that you’re prioritizing your relationship with that person over competing uses for your time. An AI system may not be able to do this. Toward the end of the 2013 movie Her, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) is shocked to learn that his AI assistant Samantha (Scarlett Johansson) is having 8,316 simultaneous conversations. Paradoxically, the ability to network with everyone simultaneously might actually make AI systems worse at networking.

It’s also important that human beings have identities that extend beyond their role at work. A common way to deepen a professional relationship is to spend time together outside of business hours. Close friends get to know one another’s spouses and kids, visit one another’s homes, go on trips together, and so forth.

It’s hard to imagine AI systems ever being able to participate in rituals like these. AI systems don’t have spouses, children, or homes. Even if an AI system has human-level intelligence and a robot body, are people going to invite it along on a ski trip or to a child’s birthday party?

It’s hard to say how friendship might evolve if we end up with actual AI systems with human-level intelligence and the capability to talk to thousands of people at once. But it seems likely that in this world humans will give priority to friendships with other humans.

So I expect that the highest levels of most professions will continue to look the way they do today: human beings connected by a dense network of professional and personal relationships. Access to these networks will continue to be extremely valuable, and I doubt AI systems will be able to beak into them.

What a great breakdown of the different types of work that we'll continue to need humans for even in an era of powerful AI. I wrote up a forecast a few weeks ago of three archetypal jobs that will probably grow more than the BLS expects over the next decade:

https://www.2120insights.com/p/three-jobs-that-might-grow-more-than

At a high level, these are:

- Jobs where people are needed to be personally accountable for factual accuracy in fields where there will continue to be emerging knowledge (e.g. biologists, legal experts, etc.)

- Jobs where having a human is inherently valuable to the customer (therapists/counselors, and personal service workers among others, similar to the many examples you cite here)

- Jobs that require significant management decisions to be made by a directly accountable individual (managers, whether directly by regulation or downstream of it, and entrepreneurs)

I left out "jobs that require physical work, specific expertise and can perform in unpredictable environments" as I see this as a bit of a question mark over the very long run. As you mention, it will be interesting to see what the ROI of humanoid robots looks like over time.

I also appreciate your breakdown of employment across occupational categories-- if you do more detailed projections of these at some point, would be happy to collaborate!

This reminds me of a scene in William Gibson's near-future novel "Virtual Light". The main character checks into a swanky hotel and is impressed by the ro it's scurrying around cleaning and performing other menial tasks.

His more worldly companion is unimpressed, though: "That just means they can't afford to pay people to do it."

How long before products have labels proudly proclaiming, "No Bots! No robotic labor was involved in the production of this product," as a seal of high quality?