16 charts that explain the AI boom

It’s one of the largest investment booms in the post-war era.

AI bubble talk has intensified in recent weeks. Record investments combined with economic weakness have left some leery of a dip in investor confidence and potential economic pain.

For now, though, we’re still in the AI boom. Nvidia keeps hitting record highs. OpenAI released another hit product, Sora, which quickly rose to the top of the app store. Anthropic and Google announced a deal last Thursday to give Anthropic access to up to one million of Google’s chips.

In this piece, we’ll visualize the AI boom in a series of charts. It’s hard to put all of AI progress into one graph. So here are 16.

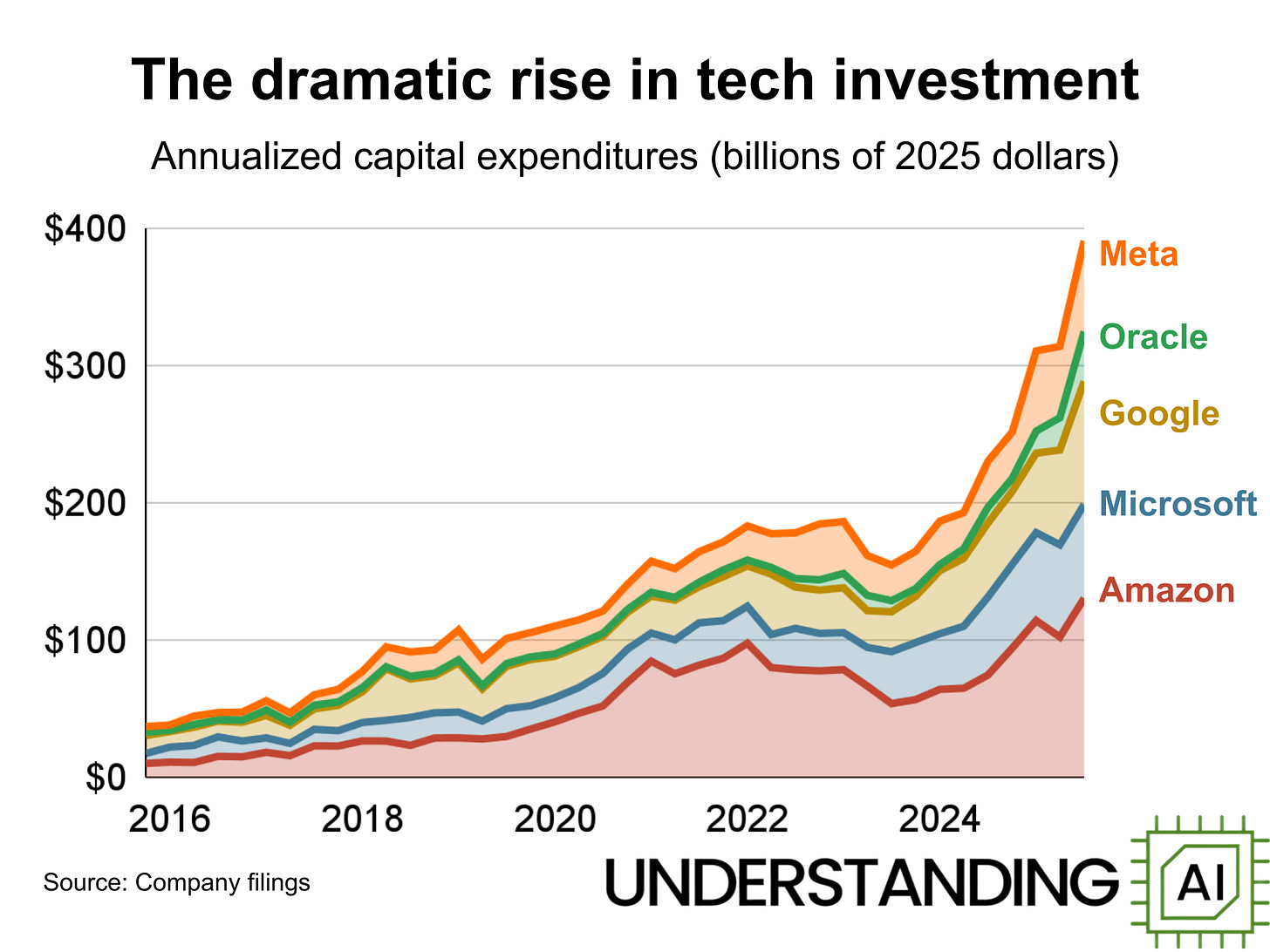

1. The largest technology companies are investing heavily in AI

If I had to put the current state of AI financials into one chart, it might be this one.

Training and running current AI models require huge, expensive collections of GPUs, stored in data centers. Someone has to invest the money to buy the chips and build the data centers. One major contender: big tech firms, who account for 44% of the total data center market. This chart shows how much money five big tech firms have spent on an annualized basis on capital expenditures, or capex.

Not all tech capex is spent on data centers, and not all data centers are dedicated to AI. The spending shown in this chart includes all the equipment and infrastructure a company buys. For instance, Amazon also needs to pay for new warehouses to ship packages. Google’s capex also covers servers to support Google search.

But a large and increasing percentage of this spending is AI related. For instance, Amazon’s CEO said in their Q4 2024 earnings call that AI investment was “the vast majority” of Amazon’s recent capex. And it will continue to grow. In Meta’s Q2 2025 earnings call, CFO Susan Li noted that “scaling GenAI capacity” will be the biggest driver of increased 2026 capex.

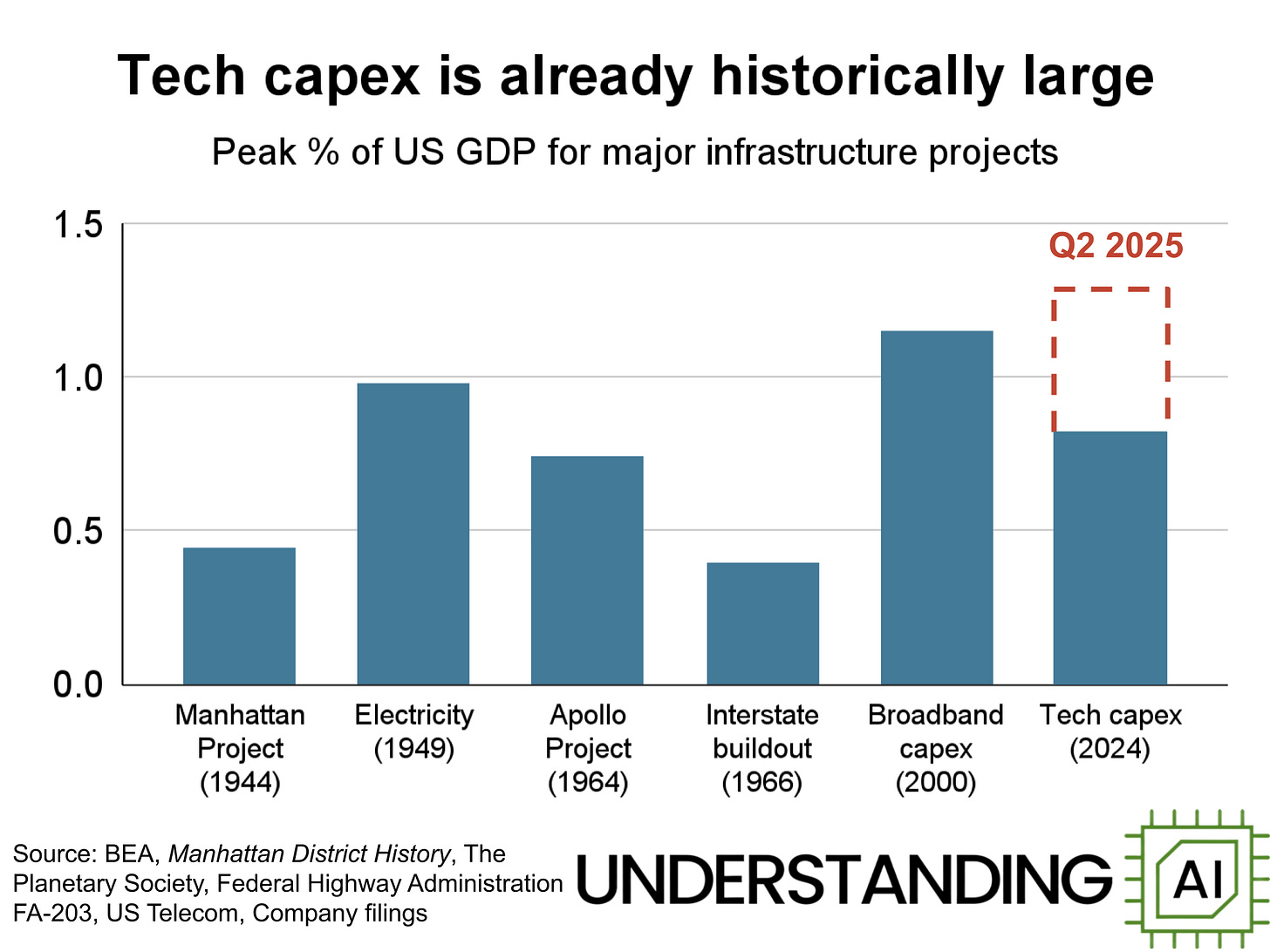

2. AI spending is significant in historical terms

Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Alphabet, and Oracle spent $241 billion in capex in 2024 — that was 0.82% of US GDP for that year. In the second quarter this year, the tech giants spent $97 billion — 1.28% of the period’s US GDP.

If this pace of spending continues for the rest of 2025, it will exceed peak annual spending during some of the most famous investment booms in the modern era, including the Manhattan Project, NASA’s spending on the Apollo Project, and the internet broadband buildout that accompanied the dot-com boom.

This isn’t the largest investment in American history — Paul Kedrosky estimated that railroad investments peaked at about 6% of the US economy in the 1880s. But it’s still one of the largest investment booms since World War II. And tech industry executives have signaled they plan to spend even more in 2026.

One caveat about this graph: not all the tech company capex is directed at the US. Probably only around 70 to 75% of the big tech capex is going to the US.1 However, not all data center spending is captured by big tech capex, and other estimates of US AI spending also lie around 1.2 to 1.3% of US GDP.

3. Companies are importing a lot of AI chips

AI chips have a famously long and complicated supply chain. Highly specialized equipment is manufactured all across the world, with most chips assembled by TSMC in Taiwan. Basically all of the AI chips that tech companies buy for US use have to be imported first.

The Census data displayed above show this clearly. There’s no specific trade category corresponding to Nvidia GPUs (or Google’s TPUs), but the red line corresponds to large computers (“automatic data processing machines” minus laptops), a category that includes most GPU and TPU imports. This has spiked to over $200 billion in annualized spending recently. Similarly, imports of computer parts and accessories (HS 8473.30), such as hard drives or power supply units, have also doubled in the past year.

These imports have been exempted from Trump’s tariff scheme. Without that exemption, companies would have had to pay somewhere between $10 and $20 billion in tariffs on these imports, according to Joey Politano.

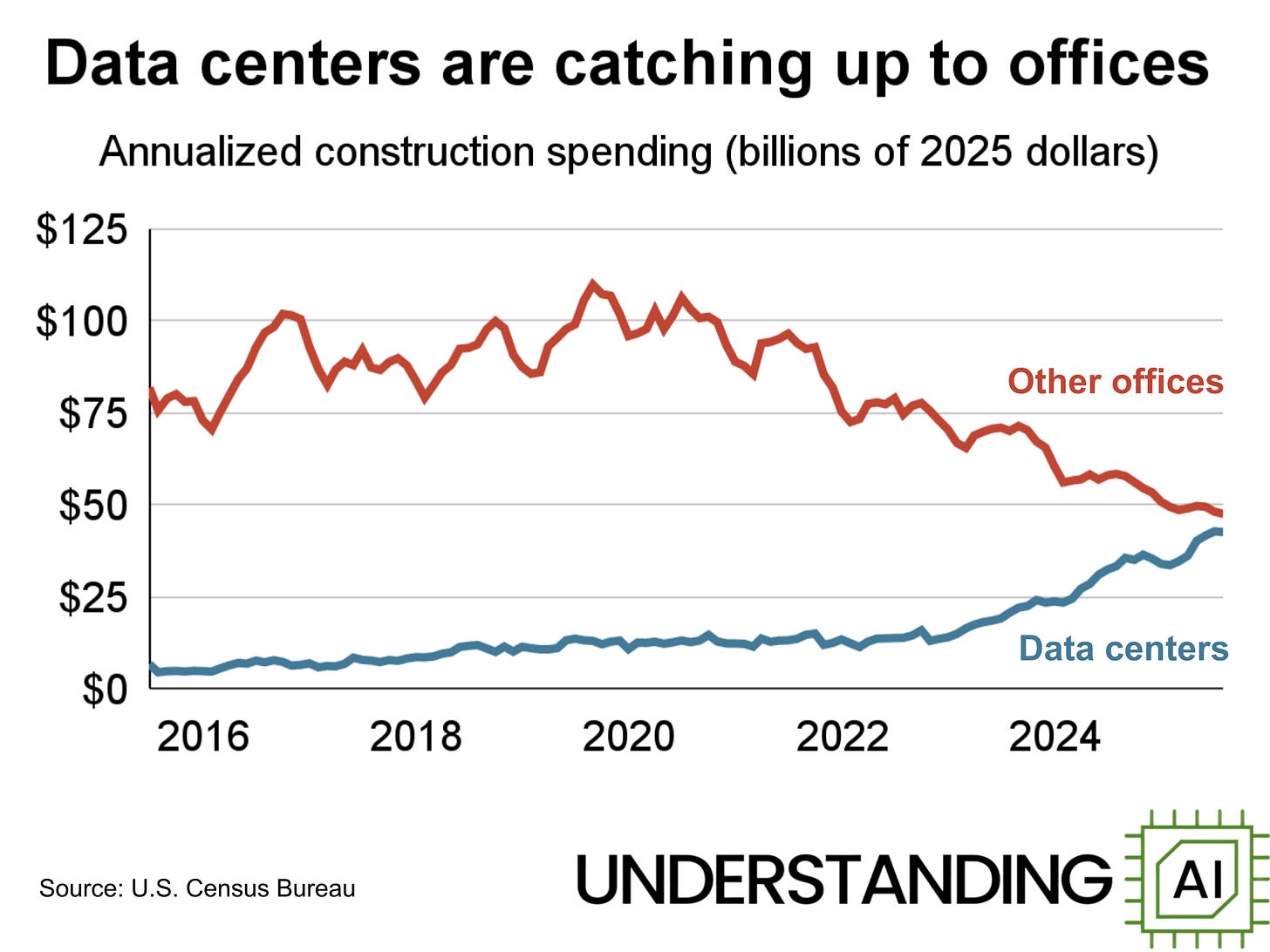

4. They’re building a lot of data centers too

The chart above shows the construction costs of all data centers built in the US, according to Census data. This doesn’t include the value of the GPUs themselves, nor of the underlying land. (The Stargate data center complex in Abilene, Texas is large enough to be seen from space). Even so, investment is skyrocketing.

In regions where data centers are built, the biggest economic benefits come during construction. A report to the Virginia legislature estimated that a 250,000 square foot data center (around 30 megawatts of capacity) would employ up to 1,500 construction workers, but only 50 full-time workers after the work was completed.

A few select counties do still earn significant tax revenues; Loudoun County in Virginia earns 38% of their tax revenue from data centers. However, Loudoun County also has the highest data center concentration in the United States, so most areas receive less benefit.

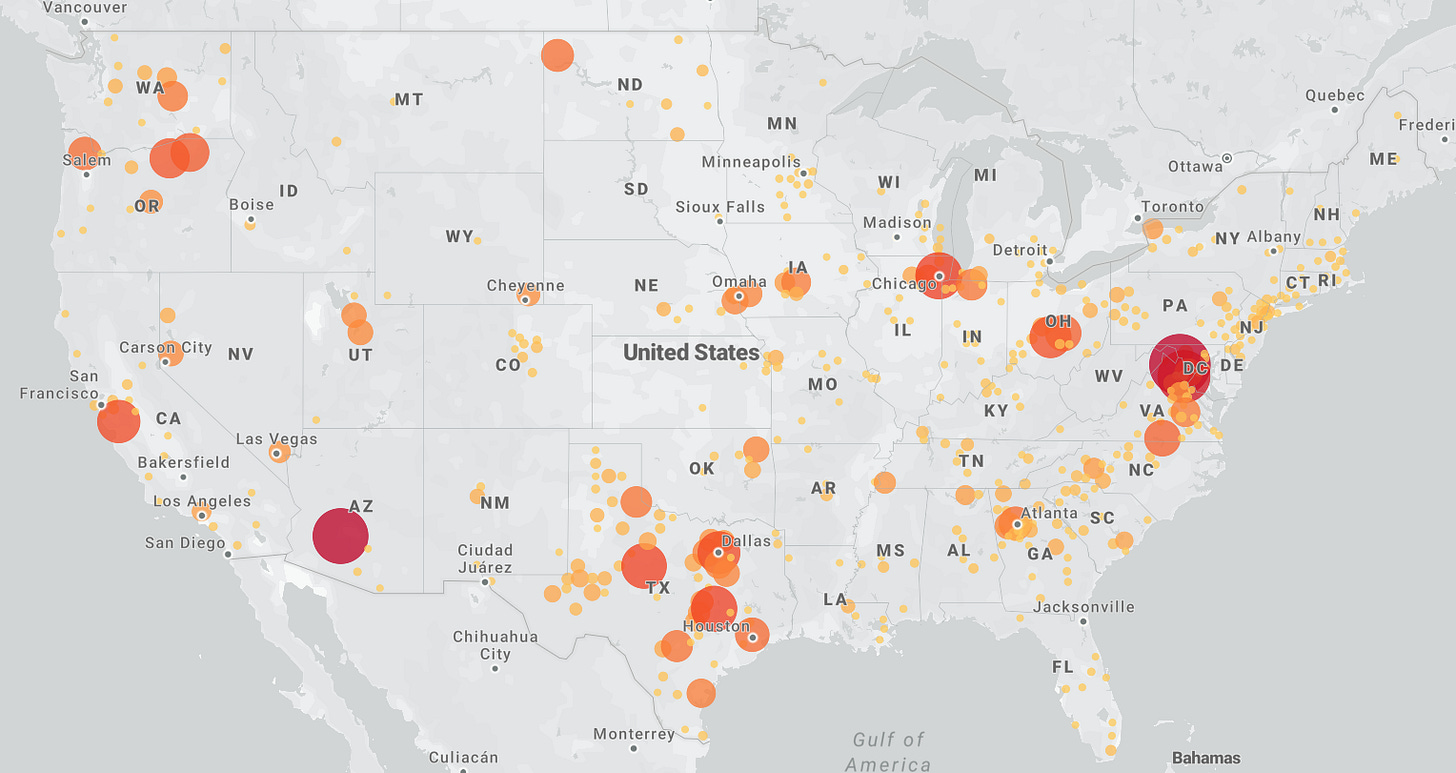

5. Data centers, particularly large ones, are geographically concentrated

This is a map from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) which shows the location of data centers currently operating or under construction. Each circle represents an individual data center; larger circles (with a deeper shade of red) are bigger facilities.

There’s a clear clustering pattern, where localities with favorable conditions — like cheap energy, good network connectivity, or a permissive regulatory environment — attract most of the facilities in operation or under construction. This is particularly true of the big data centers being constructed for AI training and inference. Unlike data centers serving internet traffic, AI workloads don’t require ultra-low latency, so they don’t need to be located close to users.

6. Few data centers are being built in California

The chart above shows ten of the largest regions in the US for data center development, according to CBRE, a commercial real estate company. Northern Virginia has the largest data center concentration in the world.

Access to cheap energy is clearly attractive to data center developers. Of the ten markets pictured above, six feature energy prices below the US industrial average of 9.2¢ per kilowatt-hour (kWh), including the five biggest. Despite California’s proximity to tech companies, high electricity rates seem to have stunted data center growth there.

Electricity prices are one major advantage that the US has over the European Union in data center construction. In the second half of 2024, commercial electricity prices in Europe averaged €0.19 per kW-hour, around double the comparable US rate.

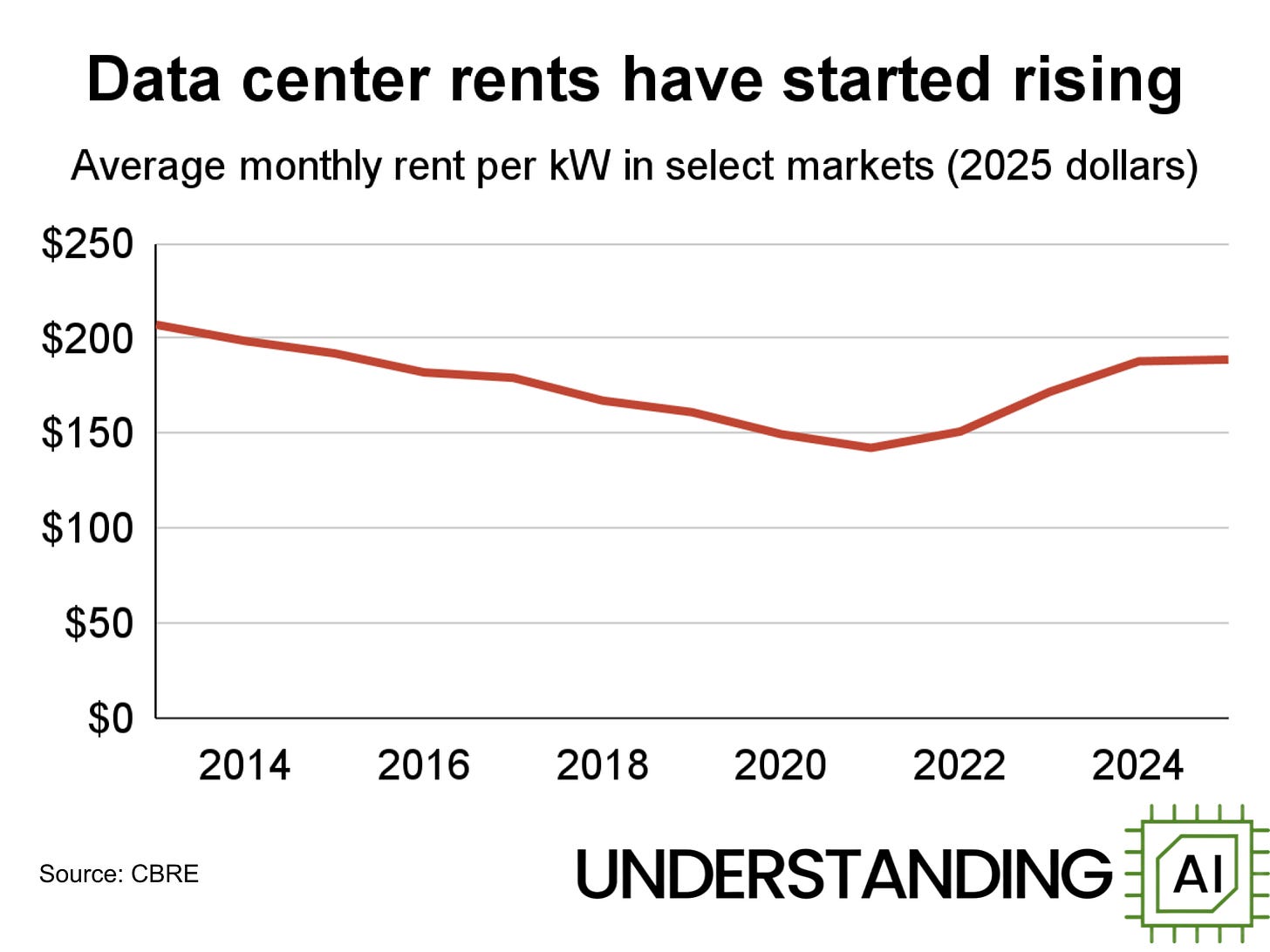

7. Low vacancy and high demand are pushing up data center rents

Companies often rent space in data centers, and the rents companies pay are often on a per kilowatt basis. During the 2010s, these costs were steadily falling. But that has changed over the last five years, as the industry has gotten caught between strong AI-driven demand and increasing physical constraints. Even after adjusting for inflation, the cost of data center space has risen to its highest level in a decade.

According to CBRE, this is most true with the largest data centers, which “recorded the sharpest increases in lease rates, driven by hyperscale demand, limited power availability and elevated build costs.” In turn, hyperscalers like Microsoft consistently claim that demand for their cloud services outstrips their capacity.

This leads to a situation where major construction is paired with record low vacancy rates, around 1.6% in what CBRE classifies as “primary” markets. So even if tech giants are willing to spend heavily to expand their data centers, physical constraints may prevent them from doing so as quickly as they’d like.

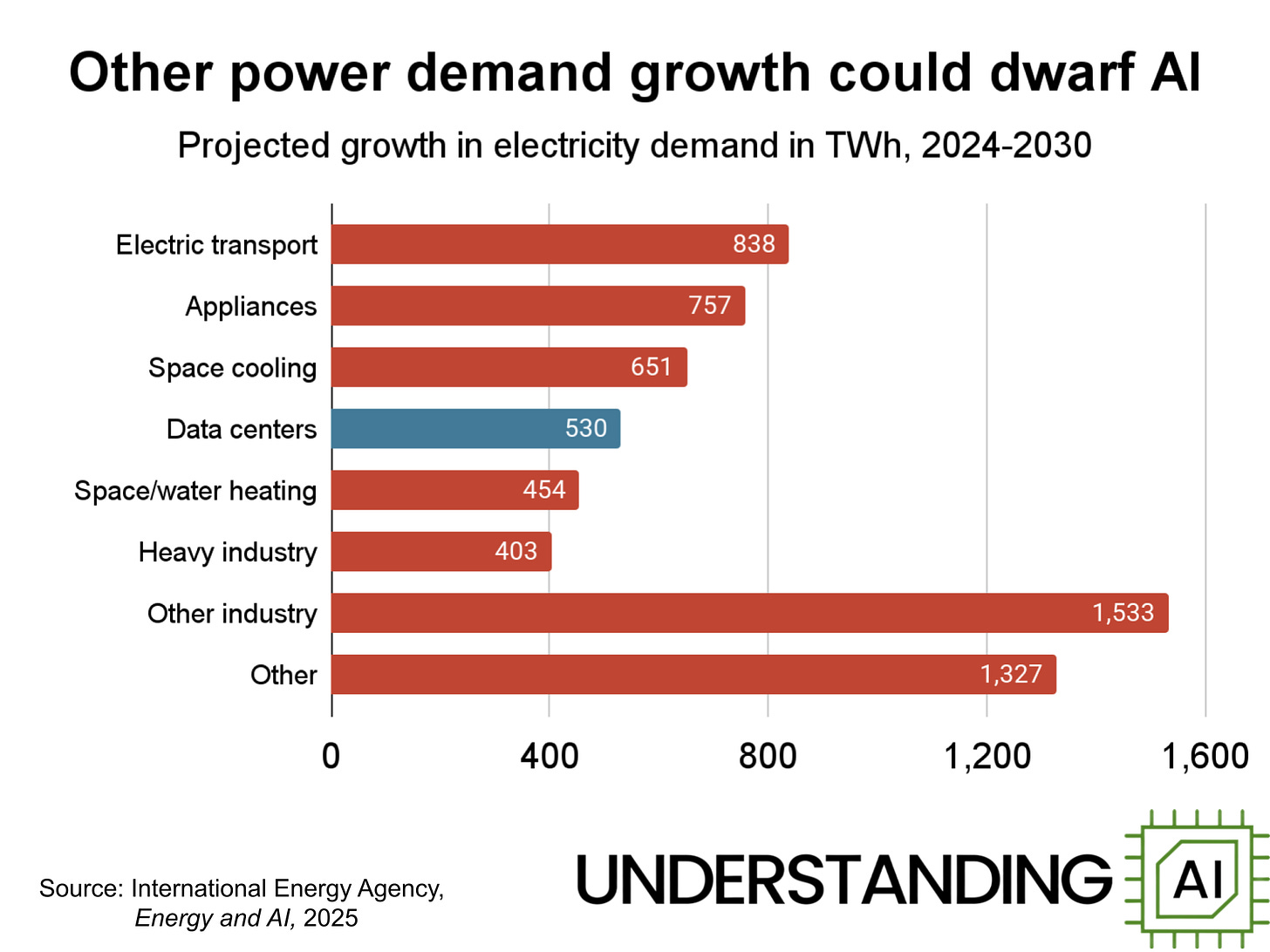

8. Data center power consumption might double by 2030 — or it might not

The International Energy Agency estimates that data centers globally consumed around 415 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity in 2024. This figure is expected to more than double to 945 TWh by 2030.

That’s 530 TWh of new demand in six years. Is that a lot? In the same report, the IEA compared it to expected growth in other sources of electricity demand. For example, electric vehicles could add more than 800 TWh of demand by 2030, while air conditioners could add 650 and electric heating could add 450 TWh.

There’s significant uncertainty to projections of data center demand. McKinsey has estimated that data center demand could grow to 1,400 TWh by 2030. Deloitte believes data center demand will be between 700 and 970 TWh. Goldman Sachs has a wide range between 740 and 1,400 TWh.

Unlike other categories, data centers’ electricity demand will be concentrated, straining local grids. But the big picture is the same for any of these estimates: data center electricity growth is going to be significant, but it will only be a modest slice of overall electricity growth as the world tries to decarbonize.

9. Water use is an overrated problem with AI

Correction 12/8/25: An earlier version of this chart included a bar for mining, which showed withdrawal rather than consumption. I concluded this isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison, so I replaced it with soybeans.

There’s been a lot of media coverage about data centers guzzling water, harming local communities in the process. But total water usage in data centers is small compared to other uses, as shown in this chart using data compiled by Andy Masley.

In 2023, data centers used around 48 million gallons per day, according to a report from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. That sounds like a lot until you compare it to other uses. AI-related data centers use so little water, relative to golf courses or soybean farming, that you can’t even see the bar.

Although some data centers use water to cool computer chips, this actually isn’t the primary way data centers drive water consumption. More water is used by power plants that generate electricity for data centers. But even if you include these off-site uses, daily water use is about 250 million gallons per day.

That’s “not out of proportion” with other industrial processes, according to Bill Shobe, an emeritus professor of environmental economics at the University of Virginia. Shobe told me that “the concerns about water and data centers seem like they get more time than maybe they deserve compared to some other concerns.”

There are still challenges around data centers releasing heated water back into the environment. But by and large, data centers don’t consume much water. In fact, if there is a data center water-use problem, it’s that some municipalities charge too little for water in dry areas like Texas where water is scarce. If these municipalities priced their water appropriately, that would encourage companies to use water more efficiently — or perhaps build data centers in other places where water is abundant.

10. There’s a lot of demand for AI inference

It’s not often that you get to deal with a quadrillion of something. But in October, Google CEO Sundar Pichai announced that the company was now processing 1.3 quadrillion tokens per month between their product integrations and API offerings. That’s equivalent to processing 160,000 tokens for every person on Earth. That’s more than the length of one Lord of the Rings book for every single person in the world, every month.

It’s difficult to compare Google’s number with other AI providers. Google’s token count includes AI features inside Google’s own products — such as the AI summary that often appears at the top of search results. But OpenAI has also announced numbers in the same ballpark. On October 6, OpenAI announced that it was processing around six billion tokens per minute, or around 260 trillion tokens per month on its developer API. This was about a four-fold increase from the 60 trillion monthly in January 2025 that The Information reported.

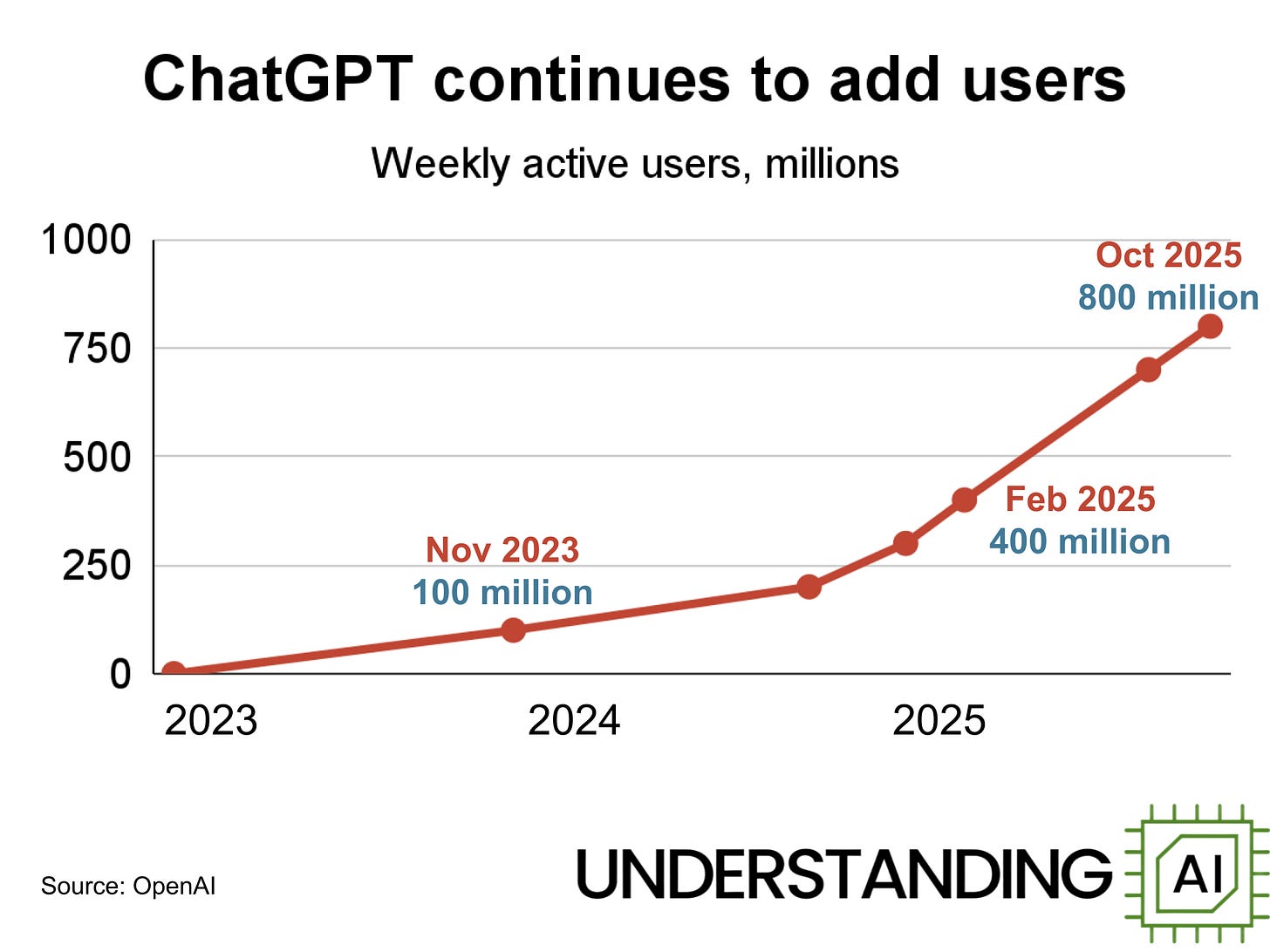

11. Consumer AI products are getting more popular — especially ChatGPT

Consumer AI usage has steadily increased over the past three years. While ChatGPT famously reached a million users within five days of its release, it took another 11 months for the service to reach 100 million weekly active users. Since then, reported users have grown to 800 million, though the true number may be slightly lower. An academic paper co-written by OpenAI researchers noted that their estimates double-counted users with multiple accounts; the numbers given by executives may similarly be overestimates.

Other AI services have grown more slowly: Google’s Gemini has 450 million monthly active users per CEO Sundar Pichai, while Anthropic’s Claude currently has around 30 million monthly active users, according to Business Insider.

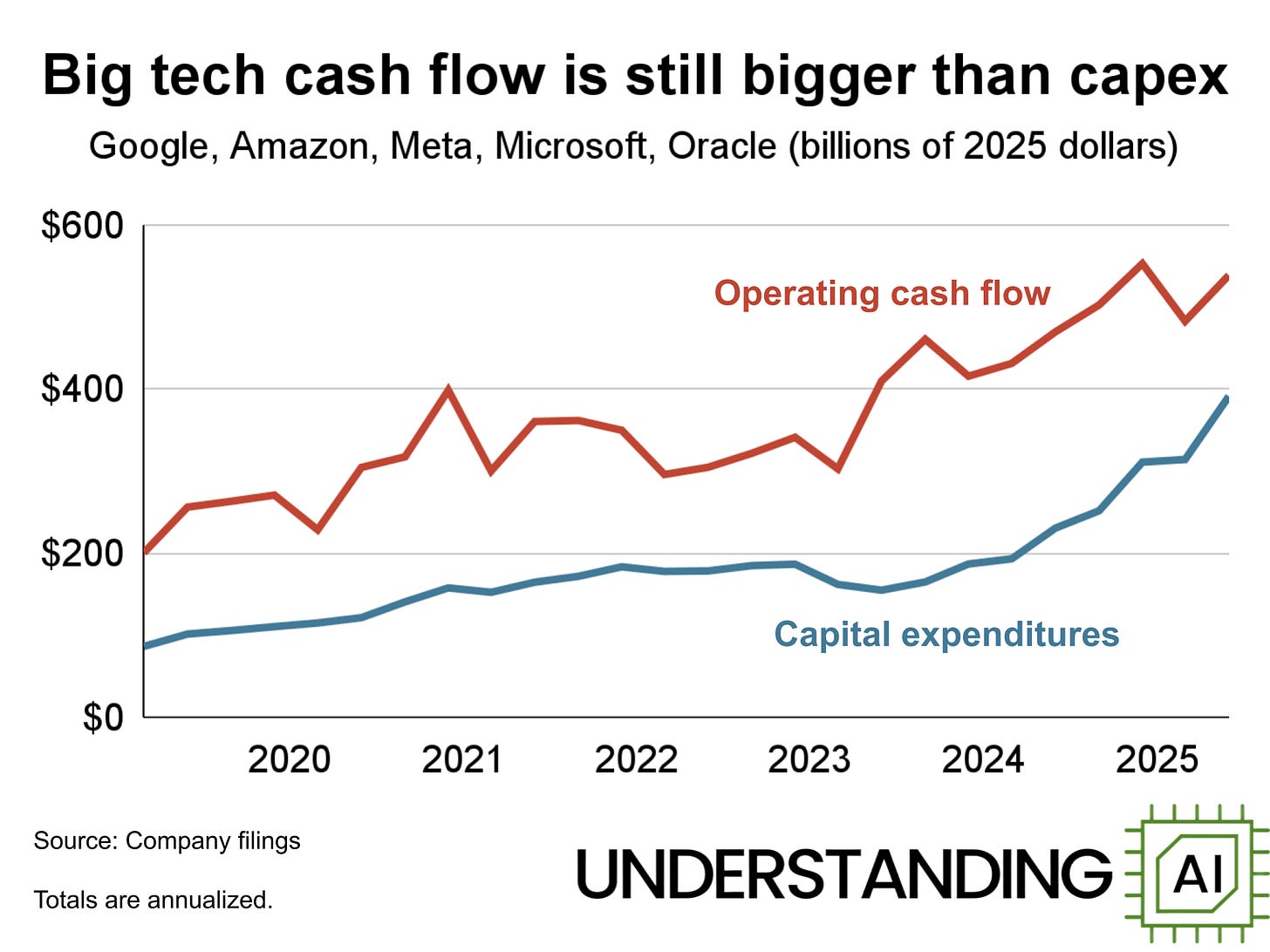

12. Tech giants have enough profits to pay for their AI investments

With such high levels of AI investment, one might worry about the financial stability of the firms behind the data center rollout. But for most of the big tech firms, this isn’t a huge issue. Cash flow from operations continues to exceed their infrastructure spending.

There is some variation among the set, though. Google earns so much money from search that they started issuing dividends in 2024, even amidst the capex boom. Microsoft and Meta have also reported solid financial performance. On the other hand, both Amazon and Oracle have had a few recent quarters with negative free cash flow (Amazon’s overall financial health is excellent; Oracle has been accumulating debt, partly as a result of aggressive stock buybacks).

There are some reasons to take companies’ reported numbers with a grain of salt. Meta recently took a 20% stake in a $27 billion joint venture that will build a data center in Louisiana, which Meta will operate. This allows Meta to acquire additional data center capacity without paying the full costs upfront. Notably, Meta agreed to compensate its partners if the data center loses significant value over the first 16 years, which means the deal could be expensive for Meta in the event of an AI downturn.

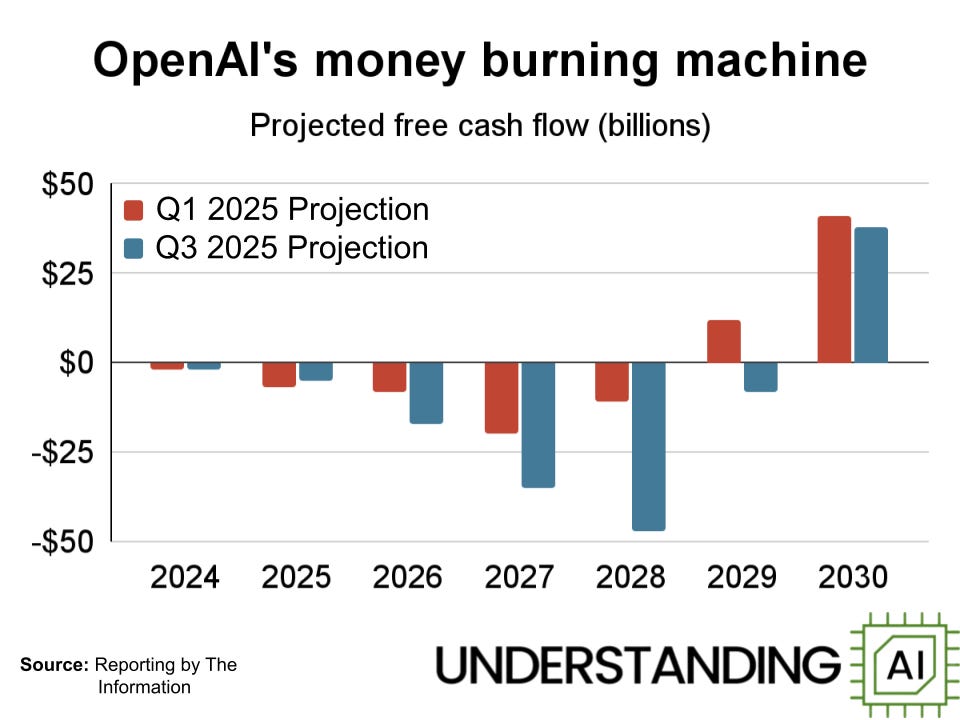

13. OpenAI expects to lose billions over the next five years

Tech giants like Google, Meta, and Microsoft can finance AI investments using profits from their non-AI products. OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI do not have this luxury. They need to raise money from outside sources to cover the costs of building data centers and training new models.

This chart, based on reporting from The Information, shows recent OpenAI internal projections of its own cash flow needs. At the start of 2025, OpenAI expected to reach a peak negative cash flow ($20 billion) in 2027. OpenAI expected smaller losses in 2028 and positive cash flow in 2029.

But in recent months, OpenAI’s projections have gotten more aggressive. Now the company expects to reach peak negative cash flow (more than $40 billion) in 2028. And OpenAI doesn’t expect to reach positive cash flow until 2030.

So far, OpenAI hasn’t had trouble raising money; many people are eager to invest in the AI boom. But if public sentiment shifts, fundraising opportunities could dry up quickly.

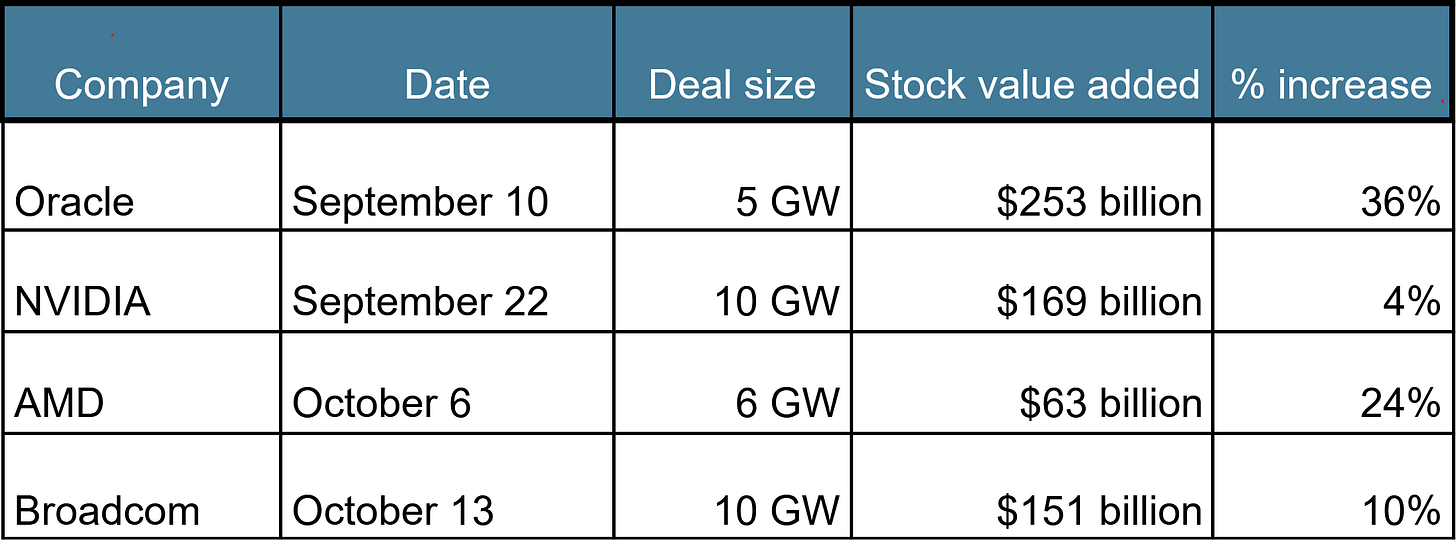

14. OpenAI deals boost partners’ stock

Over the past two months, OpenAI has made four deals that could lead to the construction of 30 gigawatts of additional data center capacity. According to CNBC, one gigawatt of data center capacity costs around $50 billion at today’s prices. So the overall cost of this new infrastructure could be as high as $1.5 trillion — far more than the $500 billion valuation given to OpenAI in its last fundraising round.

Each of these deals was made with technology companies that were acting as OpenAI suppliers: three deals with chipmakers and one with Oracle, which builds and operates data centers.

OpenAI got favorable terms in each of these deals. Why? One reason is that partnering with OpenAI boosted the partners’ stock price. In total, the four companies gained $636 billion in stock value on the days their respective deals were announced. (Some stocks have since decreased slightly in value).

It’s unclear whether these deals will fully come to fruition as planned. 30 gigawatts is a huge amount of capacity. It’s almost two thirds of the total American data center capacity in operation today (according to Baxtel, a data center consultancy).

It also dwarfs OpenAI’s current data center capacity. In a recent internal Slack note, reported by Alex Heath of Sources, Sam Altman wrote that OpenAI started the year with “around” 230 megawatts of capacity, and that the company is “now on track to exit 2025 north of 2 gigawatts of operational capacity.”

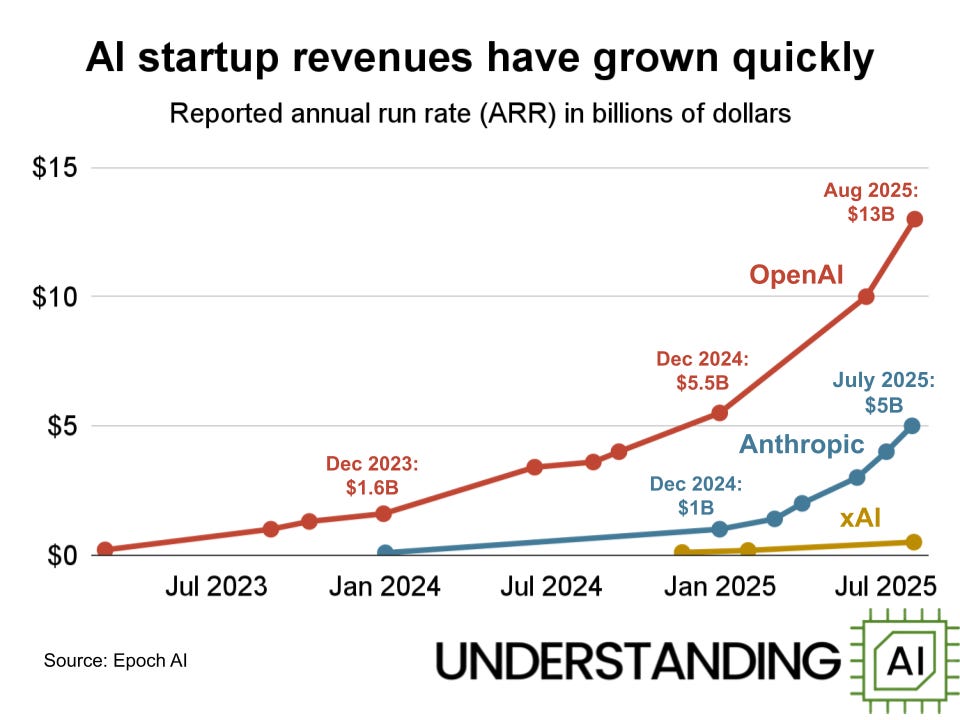

15. OpenAI’s annualized revenue has risen to $13 billion

The key question for investors is how quickly AI startups can grow their revenue. Thus far, both OpenAI and Anthropic have shown impressive revenue growth, at least according to figures reported in the media. OpenAI expects $13 billion in revenue in 2025, while Anthropic recently told Reuters that its “annual revenue run rate is approaching $7 billion.”

Both companies are still losing billions of dollars a year, however, so continued growth is necessary.

OpenAI and Anthropic have different primary revenue streams. 70% of OpenAI’s revenue comes from consumer ChatGPT subscriptions. Meanwhile, Anthropic earns 80% of its revenue from enterprise customers, according to Reuters. Most of that revenue appears to come from selling access to Claude models via an API.

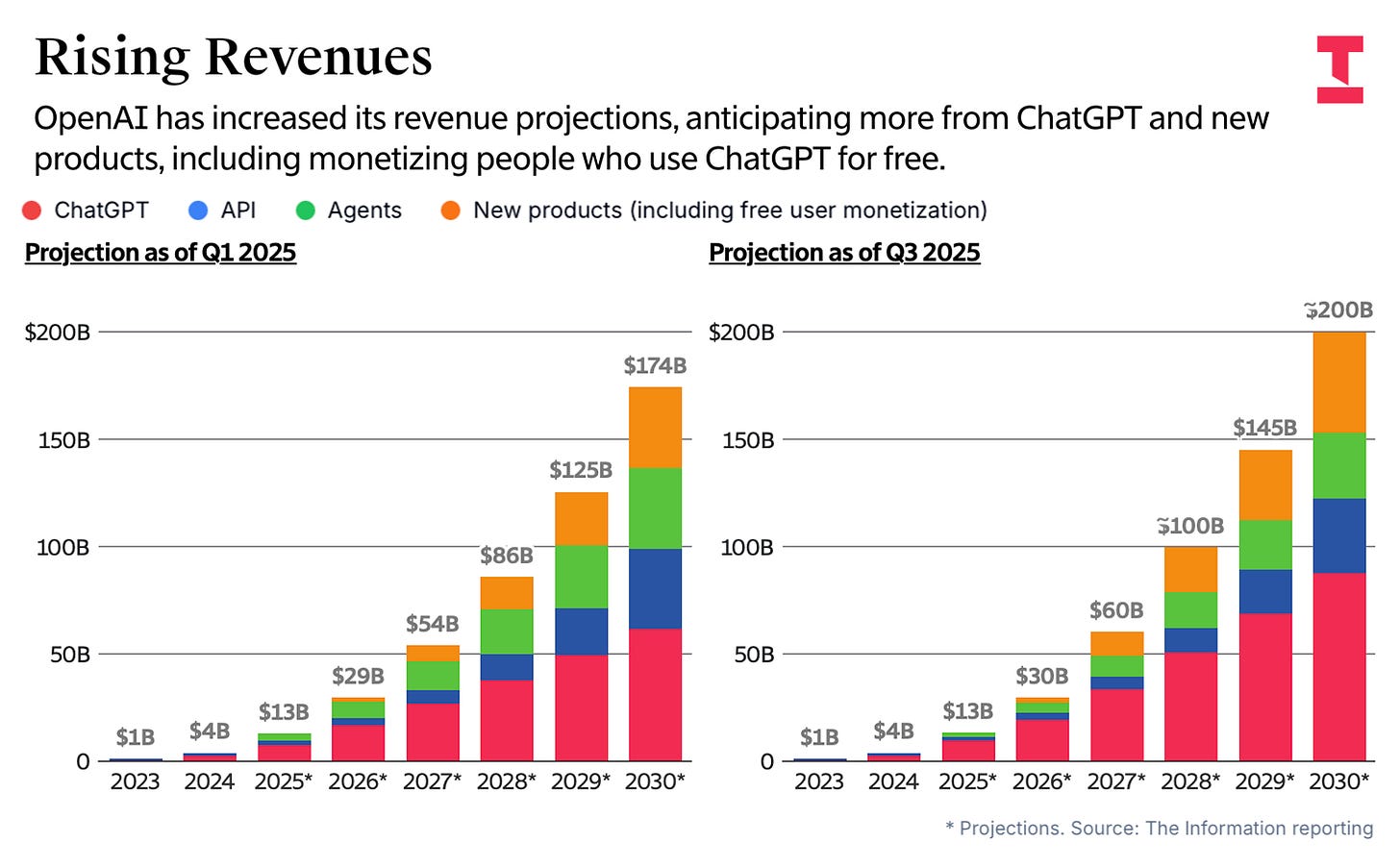

16. OpenAI predicts huge revenue growth

This chart from The Information shows OpenAI’s internal revenue projections.

After generating $13 billion this year, OpenAI hopes to generate $30 billion next year, $60 billion in 2027, and a whopping $200 billion in 2030. As you can see, OpenAI’s revenue projections have gotten more optimistic over the course of 2025. At the start of the year, the company was projecting “only” $174 billion in revenue in 2030.

OpenAI hopes to diversify its revenue streams over the next few years. The company expects ChatGPT subscriptions will continue to be the biggest moneymaker. But OpenAI is looking for healthy growth in its API business. And the company hopes that agents like Codex will generate tens of billions of dollars per year by the end of the decade.

The AI giant is also looking to generate around $50 billion in revenue from new products, including showing ads to free users of OpenAI products. OpenAI needs strategies to make money off the 95% of ChatGPT users who do not currently pay for a subscription. This is probably a large part of the logic behind OpenAI’s recent release of in-chat purchases.

Anthropic has similarly forecast that its annualized revenue could reach $26 billion by the end of 2026, up from $6 to $7 billion today.

These predictions are aggressive: a recent analysis by Greg Burnham of Epoch AI was unable to find any American companies that have gone from $10 billion in annual revenue to $100 billion in less than seven years. OpenAI predicts that it will take fewer than four.

On the other hand, Burnham found that OpenAI was potentially the second fastest company ever to go from $1 billion to $10 billion, after pandemic-era Moderna. If OpenAI can sustain its current pace of growth (roughly 3x per year), it will be able to hit its revenue targets.

Whether OpenAI and Anthropic can do so is already a trillion dollar question.

Thanks to Joey Politano, Nat Purser, and Cathy Kunkel for helpful comments on this article.

This number is based on two proxies. First, Epoch AI estimates that 74% of current GPU-intensive data capacity is located in the United States. Second, big tech companies have reported that a large majority of their long-lived assets (which includes data centers) are located in the US. Specifically, at the end of its most recent fiscal year Microsoft had 60.2% of its long-lived assets in the US. The figure was 73.5% for Amazon, 75.3% for Google, 75.6% for Oracle, and 86.2% for Meta.

It is great to see such carefully prepared work, rather than hype people vs skeptics making narrow arguments.

All of this still hinges on AI being able to improve and deliver as fast as many companies hope. I think some disappointment and some losers are quite likely, especially among weaker players and the ones who overextend themselves. Even OpenAI may not be immune, given just how much they raise the stakes.

ChatGPT use is reported to have peaked https://futurism.com/artificial-intelligence/chatgpt-peaked-data